Australia’s response to COVID in the first 2 years was one of the best in the world. Why do we rank so poorly now?

- Written by Michael Toole, Associate Principal Research Fellow, Burnet Institute

Australia’s elimination strategy during the first two years of the COVID pandemic was one of the most effective in the world. Through a combination of early border closures, widespread testing and meticulous contact tracing, localised lockdowns and mask mandates, the number of reported cases was kept to around 28,000 in 2020.

This compared with 805,000 in 2020 in the Netherlands, which has a population nine million fewer than Australia.

In 2021, Australia recorded 402,000 cases. The increase was largely due to the Delta outbreak in the second half of the year.

Fast forward to mid-2022, when Australia has leapt in rank to 15th in the world for total cases over the course of the pandemic – well ahead of countries with a similar population, such as Taiwan and Chile, and larger countries, such as Canada, Mexico and Iran.

The situation has changed dramatically this year. While Australia has reported 9,225,519 cases since early 2020, 96% have been this year. This has led to Australia’s global ranking of cases, hospitalisations and deaths being among the highest in the world.

Australia’s cases, hospitalisations and deaths

The seven-day average of new daily cases is currently just under 47,000, which is lower than the peak of 103,000 in mid-January.

Somewhat surprisingly, the number of COVID patients in hospital (5,359) is the highest since the pandemic began.

However, the number of infected persons admitted to an ICU is well below the January peak.

This may be due to higher vaccination rates than at the beginning of the year and the availability of antiviral drugs, resulting in fewer hospital cases with very severe illness. Though it’s worth noting aged care residents have been highly affected and many never made it to ICU despite severe illness.

Why is the ratio of cases to hospitalisations so high?

It’s possible that case numbers have been underestimated. A recent Conversation piece provided a number of reasons why this might be the case.

It’s also possible that BA.5 is more virulent than its Omicron predecessors, perhaps because it targets the lungs, or simply because it is more distantly related to ancestral SARS-Cov-2 and so better at immune escape than its predecessors. This might explain the high number of deaths in residential aged care facilities.

Whatever the reason, it is not unique to Australia. In Portugal, a third dose booster was associated with a 93% reduction in hospitalisation for BA.2 infections compared with just a 77% reduction for BA.5. This is equivalent to three times the risk of hospitalisation with BA.5 than BA.2.

The seven-day average of daily deaths (72) has doubled since mid-May.

Recent data from Victoria revealed those who had not received a third vaccine dose made up 72% of those who died with, or due to, COVID.

Boosters may not prevent infection but they are essential to prevent severe illness and death, especially among the elderly. And they may reduce the incidence of long COVID.

How does Australia rank globally?

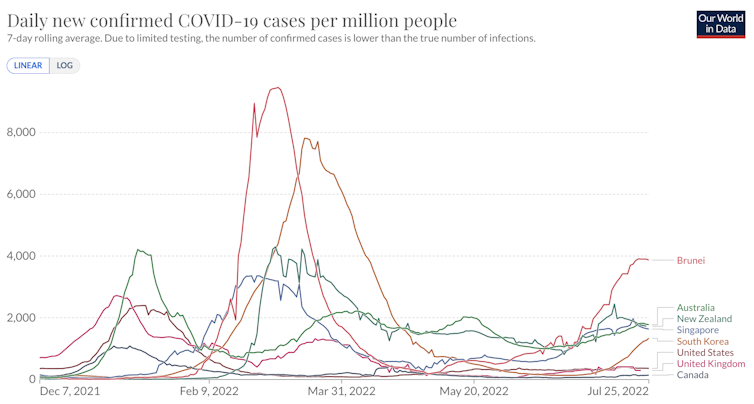

Over the past week, Australia has ranked second in the world for reported cases per million, behind Brunei and ahead of New Zealand, Singapore and South Korea, excluding small island states.