public ‘pash ons’ and angry dads – personal politics started with consciousness-raising feminists. Now, everyone’s doing it

- Written by Leigh Boucher, Associate Professor, History, Macquarie University

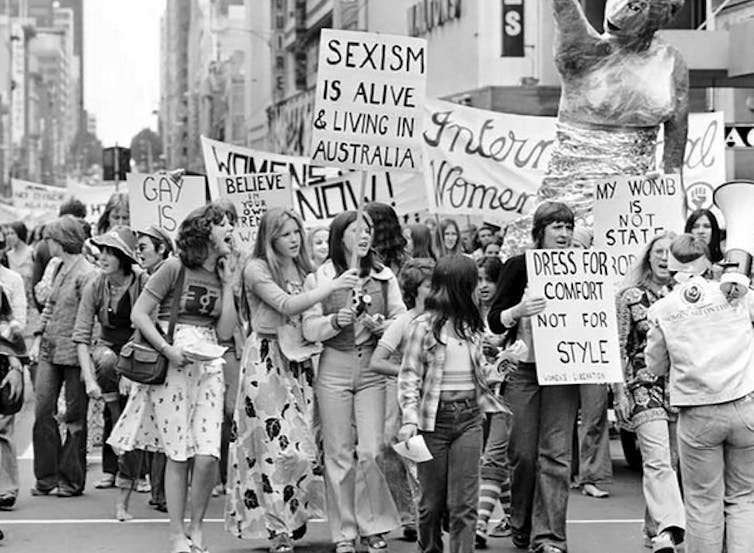

On March 17–18 1973, more than 600 women gathered in Sydney for a “Women’s Commission”. Speaking to broad themes such as motherhood, work and sexism, dozens of women recounted their struggles: to obtain contraception, or a decent education, to complain about the chauvinistic men in their workplaces. Women shared personal stories they had never told in public before, building trust, forging sisterhood.

While most of the media were excluded from the gathering, a journalist from the Australian Women’s Weekly was permitted to attend. She explained to her readers this was not just a chance to complain, but “out of a mass of personal testimony, the nature and extent of the problems facing Australian women were gradually revealed”.

The event’s goal was to transform personal stories into shared knowledge and ballast for political action. It was emblematic of the new politics of gender and sexuality in the 1970s, and it would go on to produce enormous transformations in the lives of women and sexual minorities.

Thanks to “personal politics”, the everyday lives of Australians have been transformed in areas like no-fault divorce, providing safe abortions, decriminalising homosexuality, and introducing health and welfare programs tailored to women and LGBTIQ+ people.

Political change continues to be driven by personal stories.

Non-binary mother April Long was a co-complainant, with Equality Australia, to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the 2021 Census failed to ask questions about sexual orientation, gender diversity and variations in sex characteristics. When filling in the census, “I was invisible, [our child] was invisible, my family was invisible.” The Australian Bureau of Statistics issued a statement of regret and promised to review its gender and sexual classifications for the 2026 Census.

However, describing private pain and distress has not been the exclusive political strategy of the marginalised.

Our research reveals that groups and individuals we might regard as privileged have just as effectively deployed personal stories to secure what they describe as a “return” to traditional family forms, gender roles and sexual identities.

In the late 1970s, for instance, men’s rights groups described an epidemic of despair among divorced men to argue for changes in family law. They would begin to be successful in the mid-1990s – and family law is still hotly politically contested. More recently, claims of personal distress have been weaponised against gender diversity and trans rights.

And while some of those now using personal politics are clearly conservatives, political contests over gender and sexuality cannot solely be understood through the lens of left and right. Many of the parliamentary debates produced by these campaigns have been resolved by conscience votes, because party positions on questions of gender and sexuality remain elusive.

How, then, should we assess the impact and legacy of personal politics?

Making the personal political

The phrase, and later slogan, “the personal is political” is often credited to US feminist Carol Hanisch. In her 1970 essay of the same name, Hanisch described how a growing feminist movement had been propelled by women who had come together in small groups to discuss their experiences of intimate and everyday life, in a process called consciousness-raising.

“One of the first things we discover in these groups is that personal problems are political problems,” she wrote. “There are no personal solutions at this time. There is only collective action for a collective solution.”

Women who shared their problems in a supportive group not only realised their problems were widely shared, but helped build a political movement that sought to explain and overcome them. A question as simple as “who cleans the toilet in your house?” (the answer, almost always, was women) sparked wide-ranging conversations about women’s domestic labour, men’s attitudes towards housework, and the social and cultural system that naturalised women’s responsibility for all household chores, especially the most unpleasant ones.

The slogan had purchase in Australia too. The Women’s Commission of 1973 followed the establishment of local consciousness-raising groups as a tool of transformation and discovery.

One woman told Cleo magazine in May 1974 that consciousness-raising had created “the most unbelievable change” in her when she realised she shared the same problems as the women in her group: “Gee … if I’m crazy, then they’re all crazy too!”

Gays and lesbians also found the practice energising. In 1975, the Sydney Gay Liberation Front declared in a pamphlet that its consciousness-raising group was “the guts, the heart and soul of the movement”.

“The personal is political” became a call for feminists, as well as gay and lesbian activists, to develop theories about the structures and dynamics that limited their everyday lives, and a political practice to transform them. Within a few years, speaking and writing in public about experiences of discrimination had become a prominent part of Australian national culture.

These activists drew links between oppressions in the private space of the home, offhand comments in everyday life, and the legal regimes that constrained the lives of women and homosexuals. “Overt oppression faces me every day,” said Richard Wilson, a member of Gay Liberation in Sydney, in 1973.

My parents are continually trying to straighten me out. I am continually accosted by Jesus Freaks who angrily damn me for my unnatural sins, and hatefully threaten me with God’s judgement […] I am continually intimidated by authority figures.

He described being “harassed by pigs” for publicly showing affection to another man, and being “dragged” to Glebe Police Station for “a little talk” with two detectives who “leaned” on him and another man.

“I left my husband five years ago,” wrote a woman who had found refuge at Elsie, the first feminist women’s refuge, established in March 1974, in August of that year.

My husband used to make me write my grocery lists down on paper and then I had to read it out to him and he would tell me I didn’t need all these items and then I put the prices down beside each item and add it up and that is how much money he used to give me.

Some lawmakers and critics decried this public storytelling in moral terms. They suggested it was pornographic, scandalous, trivial or some combination of all three. They were suspicious this could be a foundation for political action, dismissing it as merely “navel gazing”. For them, these concerns did not belong to the domain of politics: they were complaints about private worlds.

In 1979, John Brown, a Labor parliamentarian, dismissed these stories as exaggerated accounts from “militant feminists who trumpet aloud” their intimate troubles and sexual lives. But these activists had moved the boundaries of acceptable political speech, as well as the kinds of evidence that would be used to support arguments for change.

In that same debate, his party colleague Barry Jones noted the House of Representatives did not contain a single female voice. Feminist and gay activists occasionally set up “embassies” outside parliaments precisely because their voices were not being heard where the decisions were being made.

Bill Hayden, then leader of the Labor opposition, insisted the only way to consider the “abortion question” was to listen to “experiences (of women from) real, practical life”. This, he argued, would produce legal regimes that demonstrated “sensitivity about the rights of those people”.

Women’s stories about their own lives and experiences were becoming an expected element of political debate.

Pursuing legal change

In 1970, in every state, sex between men was criminally sanctioned, but this soon began to shift. After very limited reforms in South Australia in 1972, which provided a legal defence of privacy to the crime of sodomy, more expansive reforms were passed in that state in 1975. Reformed legislation provided near equality for homosexual and heterosexual sex.

In 1980, after a concerted campaign by the Homosexual Law Reform Coalition, Victoria passed reforms that activist Jamie Gardiner proudly proclaimed were the “best in the English-speaking world”. They removed any reference to sexual orientation in the laws and drew boundaries between criminal and lawful sex. Policing practices, however, still targeted intimacy between men in public in ways they did not target heterosexual couplings.

Slowly, over the next two decades, sex between men was decriminalised in all states and territories. The campaigns were led by activists who spoke confidently about their own experiences. Sometimes, they performed their intimate lives in public to campaign for change.

Public “kiss-ins” were a useful strategy. In 1979, activists gathered outside a pub in Melbourne to protest discriminatory policing. And in 1995, activists “pash’d on” in Taylor Square in Sydney, inviting the public to discern any difference between the intimacies of straight, gay and lesbian couples.

In 1975, the Whitlam government finally passed the Family Law Act, after two previous attempts. The Act introduced no-fault divorce to Australia and was heralded as a feminist success story.

Since 1959, laws had required the attribution of fault in the legal dissolution of a marriage. This substantively shaped the financial settlements that followed. Women who found the courage to leave unhappy or violent relationships in the 1960s were often deemed to have “deserted” their marriages. It was no coincidence that nearly 50% of Australians beneath the poverty line in the early 1970s were single mothers.

Feminist activism had revealed the home could be a space of profound oppression, and argued for a legal framework that did not reinforce these inequalities. In 1976, stories abounded of women flocking to court to free themselves from coercive, limiting marriages.

Transforming abortion laws proved thornier. By 1975, abortion had been reformed in the Northern Territory and South Australia. In New South Wales and Victoria, evolving case law provided specific defences to the crime of abortion – enabling safe abortion to be provided more widely in private clinics and a few hospitals. From 1975, Medibank rebates were nationally available for the procedure, making it more accessible.

With these case law protections in place, by 1975, a reporter from The Age was surprised to discover an expansive abortion ecosystem. He noted a woman could procure a safe abortion “virtually on request and without fear of prosecution”. However, abortion retained an ambiguous legal status in many states.

Abortion is now decriminalised in every jurisdiction in Australia. A 2021 study found 76% of Australians support access to abortion. But abortion provision remains contested.

Some publicly funded Catholic hospitals will not provide terminations, producing what activists described last year as a postcode lottery for legal healthcare. Public and private provision is rare outside the big cities.

Strange political bedfellows

This new form of politics produced passionate commitment from those inside and outside parliaments, which also placed politicians under considerable pressure.

In relation to that 1979 debate, for example, more than 10% of all the petitions submitted to parliament that year concerned abortion. It took a long time to table all these representations.

Parliamentarians also complained their offices had ground to a halt under a deluge of phone calls and letters from concerned constituents. The attorney general was sure the 1975 Family Law debate was one of the longest in living memory.

These debates also confounded the two-party system that organised Australian parliamentary politics. While Labor and the Liberal party (and its predecessors) had long disagreed about the economic principles that should govern Australia, both parties assumed that a woman’s primary duty was to maintain a heterosexual family, and to produce children who would replicate this model in future generations.

Activism that challenged this view – often by telling stories about the inequalities and oppressions of sexual and family life – challenged the heteronormative foundations of both parties.

This often fractured parties down the middle, and consensus on the politics of gender and sexuality remained elusive. As a result, many of the debates prompted by personal politics were resolved in parliament by allowing politicians to cast conscience votes. This meant party discipline would not determine how MPs voted, nor how they would respond to this politics in public life. It sometimes produced strange political bedfellows, as Labor and Liberal MPs voted together.

Several key pieces of Commonwealth legislation were passed because members were released from party discipline: the 1975 Family Law Act, a 1979 motion to protect Medibank funding for abortions, the 1983 Sex Discrimination Act, and the more recent legalisation of same-sex marriage. Parliamentary debates about state abortion laws were almost always resolved by conscience votes.

This also made their outcomes much less predictable, and MPs sometimes found their individual positions scrutinised much more closely. From 1972, the Women’s Electoral Lobby surveyed individual candidates, rather than parties, about their positions on various issues concerning women.

Our research reveals a political culture less determined by party divides than we might expect: one often punctured and animated by questions of intimate, family and sexual life.

Intimate suffering as a political tool

Stories of distress and pain have often been key weapons in the arsenal of personal politics. In the 1980s, the intimate languages of grief and suffering often reinforced political claims during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

While gay men were not the only group affected by this epidemic, they were perhaps the most heavily impacted by its consequences. Candlelight vigils, held annually from 1985, combined the collective expression of grief with powerful claims for government action. The first vigil in NSW, in 1985, ended at the state parliament, where activists protested about recent legislation that forced doctors to disclose the identities of HIV-positive patients to the government.

Later, in 1992, activists recreated a hospital ward on the front lawn of the NSW health minister, where men forced a public engagement with their suffering and distress. This was no performance, however: the men in those beds needed hospital admissions. They confronted the public with their ravaged bodies to seek more hospital beds to deal with the epidemic. About a week later, on February 4, one of those hospital-bed protesters, Brian Hobday, lost his battle with HIV/AIDs.

Once, it would have been unthinkable for a government to fund a health program to address the needs of gay men. But by the 1990s, they were funding organisations that sent “safe-sex sluts” to hand out condoms at gay-dance parties to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDs.

But marginalised and oppressed groups who had been excluded from full citizenship and participation in political debate were not the only ones to mobilise stories of intimate distress to seek change. Groups that sought very different legal reforms were also using personal stories for political effect.

Family Court violence

Men’s and fathers’ rights groups emerged in the lead-up to the 1975 Family Law Act and have continued to push back against feminist-led reforms to family life since.

Groups such as the Divorce Law Reform Association emerged in the late 1960s, sharing stories of distressed fathers who were required, by law, to support their divorced spouses and children.

After the Family Law Act passed, a rather angry masculinist activism argued for the “return of the fault factor”. The association’s president threateningly predicted “violence” if these male “victims” of oppression did not have their grievances recognised.

The Lone Fathers’ Association circulated stories of men who “considered kidnapping, even suicide” because of delays in the Family Court and a sense they were not being given a “fair go”.

Such groups argued the Family Law Act had turned divorced fathers into wage-slaves because they were required to provide child support, even if they had very limited custody.

No-fault divorce, the Divorce Law Reform Association argued, was making it “too easy” for women to leave marriages. At a Senate inquiry in 1980, it argued legal determinations of fault were required to “preserve the benefits, worth, stability and integrity of marriage” and prevent an ocean of male distress that was unfolding without it. A father was, and should remain, “the head of his own house”, the association argued.

In the early 1980s, the Family Court, its judges and their families became the target of lethal violence. Between 1980 and 1985, a series of bombings and shootings resulted in the death of one Family Court judge and another judge’s wife. They also resulted in the serious injury of Family Court judges. In 1984, the Family Court in Parramatta was bombed, though in this case no one was injured.

One 1983 book published during this reign of terror argued fathers had been “judicially discarded” by the court and it was the denial of their rights as fathers that drove this violence. It opened:

Tragedy. Heartbreak. Shock. Confusion. Despair. These are too often the bitter fruits, the luckless harvest of so many people who have been through the process of the Family Court.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, activists secured sympathetic coverage of a spate of murder-suicides in which men killed their families and themselves. The press positioned these men as confused and desperate victims, driven to violence by a legal system that had been transformed by feminist thinking.

The “cause” of this violence, whether directed towards judges or families, was widely represented as a Family Court system that did not attend to men’s needs. As feminist scholar Therese Taylor observes, these activists had managed to turn “murder into the final proof of paternal love”.

Men’s sheds, Safe Schools and funding

From the mid-1990s, “men’s sheds” proliferated across Australia, and from 2010, they began to receive Commonwealth funding. There are now at least 1,250 of them (with access usually restricted to men). They promise to address isolation, poor mental health and suicide among (particularly older) men by providing “traditional” male activities and social contact.

The Australian Men’s Shed Association provided personal testimonies in its submission to a 2009 Senate Inquiry, which would eventually lead to the first injection of Commonwealth funding. After retirement, said Rob), “at times I was so distressed and nervous that I couldn’t think straight and in those darker moments I sometimes thought of doing myself in”. He said he “came to the men’s shed to get my mind out of the darkness and to occupy myself”.

Men’s sheds have been big winners under the National Men’s Health Policy, with additional remarkable success in state-based grant programs. In 2010, Men’s Sheds were awarded Commonwealth funding to support their expansion across Australia. In 2020, their funding was increased. A recent report commissioned by the Commonwealth government found most sheds reported being “well-funded and well-resourced”.

A very different fate befell the Safe Schools program, a health education project developed to better support gender- and sexually diverse children and teenagers. The voluntary program, which provides education materials and support for teachers, was developed in Victoria and was rolled out nationally with Commonwealth support in 2014.

Two years later, in 2016, conservative campaigners pressured schools and governments to wind back the program. This prompted an outpouring of community support. Queer and trans youth spoke powerfully in nationwide rallies about the impact the program had on their lives.

At a Perth rally in 2016, 15-year-old Oscar, a self-identified LGBTIQA+ Australian, explained why safe schools are needed. “For many students, school is a battleground – social rejection, abuse, peer-shunning and isolation turn life into a daily struggle,” he said. By “gutting” Safe Schools, the government was risking “not only the safety but the very mental health and the very lives of our children”.

A formal review commissioned by the Commonwealth government found that Safe Schools material was effective and appropriate. And yet, Commonwealth funding was discontinued after 2017, although some state governments stepped in, either to directly replace the federal funding or to fund programs that reflected the principles of Safe Schools.

Both men’s sheds and the Safe Schools program provide safe spaces and address poor mental health. Both have used shared personal stories of distress to argue for their existence. But while funding for men’s sheds is ever increasing, a gender-specific program of support for young LGBTIQ+ people found that the dissemination of personal stories of distress could not defeat their opponents.

What next?

Personal stories of suffering and distress have been potent political tools for women’s and gay rights. But they have also been effectively wielded by groups that seek to reinforce what they describe as a “traditional” gender and sexual order. It seems important to remember, then, that 1970s activists identified how those “traditions” maintained inequality and oppression.

Today, the personal is (still) political. Political contests around gender and sexuality will inevitably continue to provoke and unsettle. The next battlegrounds are trans rights, the continuing struggle to maintain and expand reproductive health care, including abortion services, and meaningful action on gendered violence, including family law reform and improved support for legal aid and women’s refuge services.

Personal storytelling is affecting and politically effective, but justice cannot be achieved through storytelling alone. To rely on storytelling risks becoming trapped in a politics of competitive complaint that reinforces disagreement, rather than seeking collective transformation. Activists need to engage in full-throated, nuanced critiques of a gender and sexual order that still works to marginalise, exclude and oppress.

The most effective campaigns have not simply told personal stories; they have made powerful arguments about inequality and injustice that mobilised Australians to engage in the political process. They have also, more often than not, resisted a politics of reassurance and recognition. Instead, they have admitted they are actively challenging the status quo.

This essay draws on Personal Politics: Sexuality, Gender and the Remaking of Citizenship in Australia by Leigh Boucher, Barbara Baird, Michelle Arrow & Robert Reynolds (Monash University Press).

Authors: Leigh Boucher, Associate Professor, History, Macquarie University