Apple wants to know if you’re happy or sad as part of its latest software update. Who will this benefit?

- Written by Peter Koval, Associate Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne

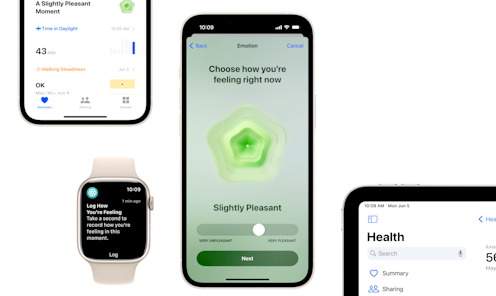

Apple’s iOS 17 operating system is expected to drop any day. The software update comes with several new features, including a tool for daily mood and emotion logging – a technique known to emotion researchers as “experience sampling”.

Although there are caveats, certain mental health studies have shown that regularly recording one’s feelings can be useful. However, given the vast amount of health data Apple already harvests from customers, why does it also want to record their subjective feelings? And how helpful might this be for users?

How it works

With the latest software update, Apple’s in-built Health app will allow iPhone, iPad and Apple Watch users to record how they feel on a sliding scale from “very unpleasant” to “very pleasant”.

Users will then select from a list of adjectives to label their feelings and indicate which factors – including health, fitness, relationships, work, money and current events – have most influenced how they feel.

The goal is to give users daily and weekly summaries of their feelings, alongside data on factors that may have influenced them. Apple claims this will help users “build emotional awareness and resilience”.

Why does Apple care about our feelings?

Apple already collected copious amounts of health data prior to this update. The iPhone is equipped with an accelerometer, gyroscope, light meter, microphone, camera and GPS, while the Apple Watch can also record skin temperature and heart rate. Why does Apple now want users to log how they feel as well?

Driven by a range of potential applications – from fraud detection to enhanced customer experience and personalised marketing - the emotion detection and recognition industry is projected to be worth US$56 billion (A$86.9 billion) by 2024. And Apple is one of numerous technology companies that have invested in trying to detect people’s emotions from sensor recordings.

Read more: Imagine if technology could read and react to our emotions

However, scientists are divided over whether emotions can be inferred from such bodily signals. Research reviews suggest neither facial expressions nor physiological responses can be used to reliably infer what emotions someone is experiencing.

By adding self-report to its methodological toolkit, Apple may be recognising that subjective experience is essential to understanding human emotion and, it seems, abandoning the goal of inferring emotions solely from “objective” data.

The science behind experience sampling

Apple’s new feature allows users to record their feelings “right now” (labelled emotions) or “overall today” (designated moods). Is this a valid distinction?

Although scientific consensus remains elusive, emotions are typically defined as being about something: I am angry at my boss because she rejected my proposal. On the other hand, moods are not consciously tied to specific events: I’m feeling grumpy, but I don’t know why.

Apple’s two reporting methods don’t neatly distinguish emotions from moods, even though they rely on different cognitive processes that can produce divergent estimates of people’s feelings.

If the new feature allowed users to independently select both the time frame (momentary or daily) and type of feeling (directed emotion or diffuse mood) being experienced, this could help make users more aware of biases in how they remember feelings. It may even help people identify the often obscure causes of their moods.

Apple’s feeling slider asks people how pleasant or unpleasant they feel. This captures the primary dimension of feeling, known as valence, but neglects other essential dimensions.

Moreover, scientists debate whether pleasantness and unpleasantness are opposite sides of a continuum, as the feature assumes, or whether they can co-occur as mixed emotions. Measuring pleasant and unpleasant feelings separately would allow users to report mixed feelings, which are common in everyday life.

Some research also suggests knowing how pleasant and unpleasant someone is feeling can be used to infer the second fundamental dimension of their feelings, namely their level of arousal – such as how “tense” or “calm” they are.

After they have rated the valence of the feelings, Apple’s feature asks users to label their feelings using a list of adjectives such as “grateful”, “worried”, “happy” or “discouraged”.

Do these options capture the breadth of human feelings? The number of unique emotion categories – or whether discrete emotion categories exist at all – is a topic of ongoing scientific debate. Yet, Apple’s initial list of feeling categories provides pretty decent coverage of this space.

What are the benefits?

Apple’s claim that mood and emotion tracking may improve users’ wellbeing is not unfounded. Research has shown monitoring and labelling feelings enhances people’s ability to differentiate between emotions, and helps them cope with distress. Both of these are key ingredients for healthy psychological functioning.

Beyond that, emerging research suggests that patterns of moment-to-moment fluctuations in people’s everyday feelings may be useful in predicting who is at risk of developing depression or other mental illnesses.

Apple’s history of research collaboration offers hope that tracking people’s feelings on a massive scale may lead to scientific breakthroughs in our understanding, treatment and prevention of common mental health disorders.

What are the risks?

At the same time, Apple is asking users to hand over yet more of their personal data – so we can’t overlook the potential pitfalls of the new feature.

Apple assures users the Health app is “designed for privacy and security” with a range of safeguards, including data encryption and user control over data sharing. It guarantees health data “may not be used for advertising, marketing, or sold to data brokers”.

This may sound encouraging, but Apple’s data privacy record is far from perfect. The company was recently fined by French authorities for using customers’ data for targeted advertising without consent.

Detailed data on users’ self-reported moods and emotions could also potentially be used for advertising products and services. The potential for misuse and commodification of sensitive mental health data is real, suggesting a need for stricter regulation over how companies collect, store and use customers’ data.

Before you dive into using Apple’s new mood and emotion-tracking feature, we’d urge you to consider whether the risks outweigh the potential benefits for you.

Authors: Peter Koval, Associate Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne