new research reveals the threats and daily trauma judges face in their jobs

- Written by Kevin O’Sullivan, Conjoint Senior Lecturer, UNSW

As a judicial officer, being subject to death threats not only for you but your family is a concern […] you are expected to simply soldier on and go to work the next day.

You can’t un-see or un-hear the material; and it’s impossible to forget, particularly when it involves very young children.

There is a cumulative effect for me, getting worse year by year.

These are some of the distressing sentiments that judges in NSW revealed as part of a recent study I conducted with colleagues at UNSW on the stresses they face in their jobs.

In surveys of 205 serving and retired members of state courts, we found the majority were exposed to alarming levels of traumatic experiences on a daily basis.

This included a high incidence of threats of physical harm to themselves and their families. Perhaps most worrying were the 47 respondents (about 25%) who had received death threats, and those whose families and/or children had been threatened with harm or death.

These types of threats are typically made by individuals with the means and motive to carry them out — namely, defendants in criminal cases and their associates. Said one respondent,

An offender smuggled a knife into the courtroom and was waiting for an opportunity to stab me. An attentive sheriff intervened before the opportunity arose.

Read more: Jury is out: why shifting to judge-alone trials is a flawed approach to criminal justice

‘Soldier on and go to work the next day’

Added to these stresses is the sometimes daily exposure to the cruel and sadistic behaviour of defendants to other adults and children, including physical and sexual violence.

Three-quarters of our respondents reported being exposed to events associated with trauma, and 30% reported symptoms consistent with trauma-related effects from being exposed to these types of cases on a daily basis.

Many respondents described the soul-destroying repetition of nastiness to which they are privy in both written and oral evidence. They also described the expectation that they “simply soldier on and go to work the next day”.

Said one participant:

The cumulative effect of witnessing violence towards and the degradation of others is a trauma which has a detrimental effect on one’s life, functioning and relationships. It is like an osmosis and manifests itself both physically and psychologically.

Judges frequently don’t have anyone to discuss these things with. Nor can they take on “other duties” to have an occasional respite from the grind. They live with their trauma and it can take a heavy toll on their health.

On top of this, and because of the very public nature of their roles, judges are considered fair game for criticism. This can sometimes be extreme and amount to vilification: they’re incompetent, they’re soft, they’re out of touch, they should have their face “smashed in”.

Sometimes this criticism comes from those in positions of power, which can carry greater weight. For instance, three federal ministers — Greg Hunt, Alan Tudge and Michael Sukkar — narrowly avoided contempt of court charges in 2018 after criticising what they perceived as lenient sentences for terrorism offences.

Usually, judges have little or no recourse to challenge such comments. The vast majority of respondents in our study said they did nothing about such vilification. Only a very small number said they had taken legal action, which, in the case of defamation, is a costly and precarious path.

Read more: Victoria's criminal courts are critically backlogged. This is how we can speed up justice

The toll on judges’ health

The costs of these pressures and repeated traumatic experiences are shown in two psychological indices we used to gauge our respondents’ well-being, the K10 and the Impact of Event Scale.

On both, the study participants scored significantly worse than the general public. I am a clinician and if someone were referred to me with these scores, I would know I was looking at serious clinical issues.

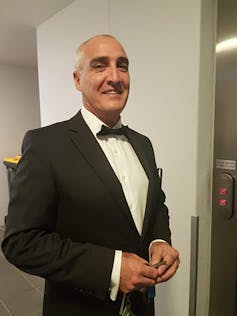

Guy Andrew, a former Federal Circuit Court judge who was found dead last October.

PR Handout Image/QLD Police

Guy Andrew, a former Federal Circuit Court judge who was found dead last October.

PR Handout Image/QLD Police

The suicide of Melbourne judge Stephen Myall in 2018 shows just how taxing and unrelenting the job can be. Myall was said to be overwhelmed by an enormous caseload and had attended a well-being course two weeks before his death.

Another judge, Guy Andrew, was found dead in Queensland last year after he was ordered to undergo counselling and mentoring following complaints about his behaviour on the bench.

A public-facing job with high costs

In societies that value the rule of law, judges are seen as the pinnacle of the system and are held in high esteem, paid well, and honoured. Their task is to weigh evidence impartially and to speak without fear or favour.

In the courtroom, the judge is the only person who sits facing the court, on show to all. This arrangement is not accidental. Justice is supposed to be public and transparent.

But judges have historically paid a high price for their status.

Judges have been murdered in recent decades in Italy (by the Mafia), the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries. Others have survived attempts on their lives.

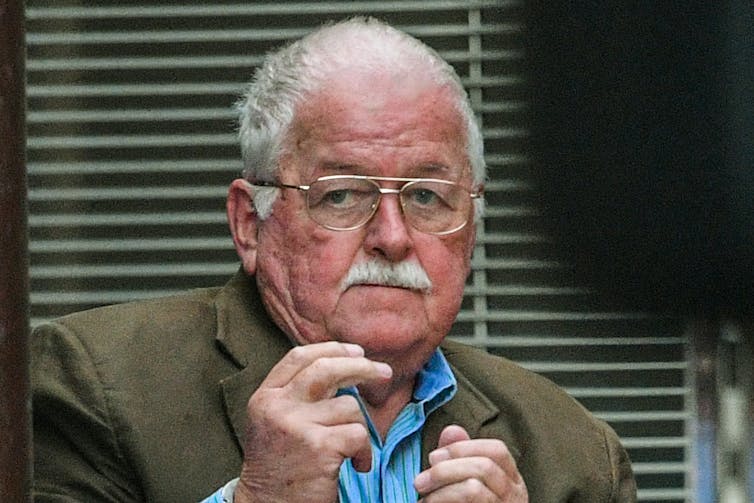

In Australia, a man named Leonard Warwick, who was embroiled in a dispute with his ex-wife, targeted several Family Court judges in the early 1980s — shooting to death one and killing another one’s wife in a bombing of his home. Warwick also bombed the Family Court at Parramatta.

Warwick evaded justice until his arrest in 2015. He was sentenced to life in jail.

Brendan Esposito/AAP

Warwick evaded justice until his arrest in 2015. He was sentenced to life in jail.

Brendan Esposito/AAP

Ways forward

If there was a silver lining in our study, it was the extraordinarily high response rate. Our judicial officers are engaged and keen to have a say in how to improve the working conditions for themselves and their fellow judges.

There were many suggestions about how to do things better, and a degree of optimism about the future. Among the initiatives put forward were

devising formal mechanisms of mutual support for judges

making stress and trauma legitimate topics of discussion in the legal community

increasing safety and security precautions in courtrooms

instituting an annual mental health check for judicial officers.

As one of our participants expressed to us, change can only come from listening to judicial officers and hearing their concerns.

Thank you for doing this [survey]. […] I see people working so hard with no real voice and a desire to do right by all. It’s pretty sad.

Authors: Kevin O’Sullivan, Conjoint Senior Lecturer, UNSW