Cutting JobSeeker payments will cause crippling rental stress in our cities

- Written by Simone Casey, Research Associate, Future Social Service Institute, RMIT University

As soon as the COVID-19 pandemic caused businesses to shut down, state governments acted to avoid evictions by introducing moratoriums, and the federal government introduced the Coronavirus Supplement of A$550 on top of the fortnightly JobSeeker payment. These measures were intended to enable 1.6 million Australians to ride out the pandemic-related business shutdowns.

This welcome but temporary support is being withdrawn. The JobSeeker supplement was reduced to A$250 a fortnight from September 26. It will end in January 2021.

Timeline of Coronavirus Supplement.

Timeline of Coronavirus Supplement.

Our modelling for Victoria shows the tapering down and withdrawal of the JobSeeker supplement will cause crippling rental stress for unemployed and underemployed private renters. In Melbourne, we have found the unemployed will face the same problem of rental stress as those on the former Newstart allowance experienced before the pandemic. (Rental stress is defined as a low-income household spending more than 30% of its income on housing costs.)

Read more: City share-house rents eat up most of Newstart, leaving less than $100 a week to live on

Before COVID, private rentals in nearly all capital cities were already unaffordable for unemployed and low-income renters even in typical share households. What makes the scenario worse than before COVID are the sheer numbers affected. Many of these people may have had incomes prior to the shock that enabled them to maintain higher rents.

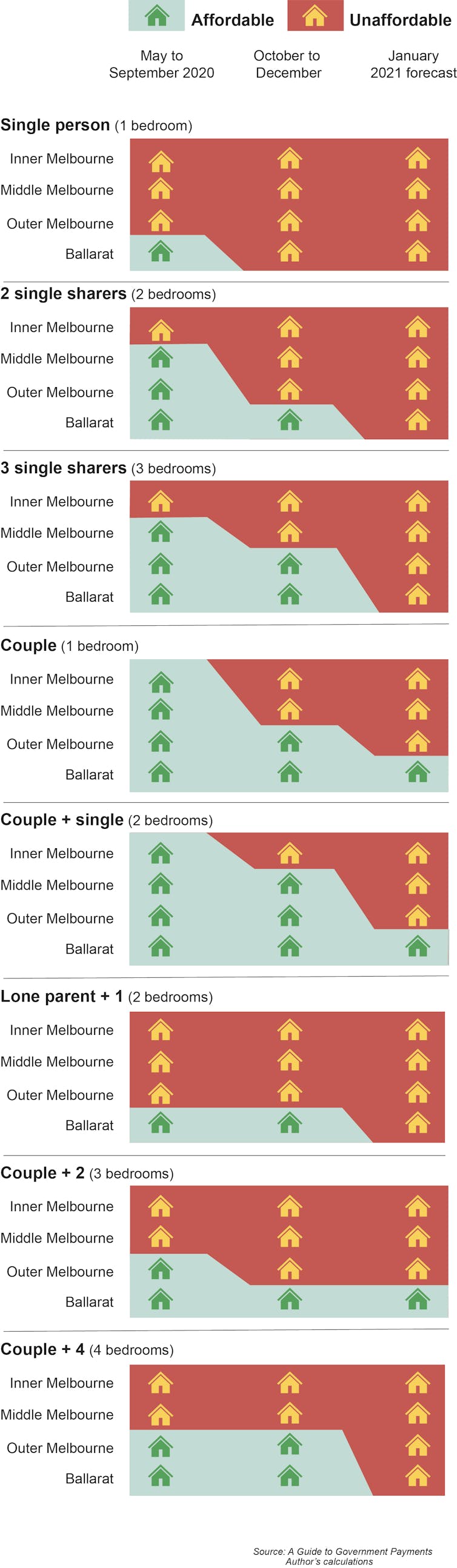

To illustrate the extent of the rental stress crisis we modelled rental affordability for the typical low-income household types in Victoria. The first chart shows the effects of the withdrawal of the supplement on rent affordability for two and three sharers and lone-parent families. The second chart later in this article shows the effects across a range of household types.

Impacts of Coronavirus Supplement withdrawal on three household types. (Median rents calculated from Real Estate Institute of Australia June 2020 data. Income calculated to include Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and lone-parent income includes Parenting Payment Single with Family Tax Benefit.)

Impacts of Coronavirus Supplement withdrawal on three household types. (Median rents calculated from Real Estate Institute of Australia June 2020 data. Income calculated to include Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and lone-parent income includes Parenting Payment Single with Family Tax Benefit.)

The modelling shows the interim rate (A$250) of the Coronavirus Supplement will help for a limited number of household types, particularly in the outer part of Melbourne and regional towns like Ballarat. However, it will not help many households in the inner region of Melbourne where rentals will remain unaffordable. This pattern is worrying because that’s where many of the jobs will become available once economic recovery is under way.

Read more: Why coronavirus will deepen the inequality of our suburbs

Households with more than one adult receiving the supplement will be better off than lone-parent households. That is because all the adults in those households receive the supplement, and lone-parent households generally need to rent properties with more than one bedroom.

Impacts of Coronavirus Supplement withdrawal on major rental household types. (Median rents calculated from Real Estate Institute of Australia June 2020 data. Income calculated to include Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and lone-parent income includes Parenting Payment Single with Family Tax Benefit.)

Impacts of Coronavirus Supplement withdrawal on major rental household types. (Median rents calculated from Real Estate Institute of Australia June 2020 data. Income calculated to include Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and lone-parent income includes Parenting Payment Single with Family Tax Benefit.)

The scenario here plays out across Australia, but is particularly bad for Victorians because the extended lockdown has deferred recovery.

COVID impacts have hit low-income households hardest

Is is important to note that the COVID economic shock has hit low-income households particularly hard. Those in precarious work, young adults and women have had the biggest hits to their incomes and jobs.

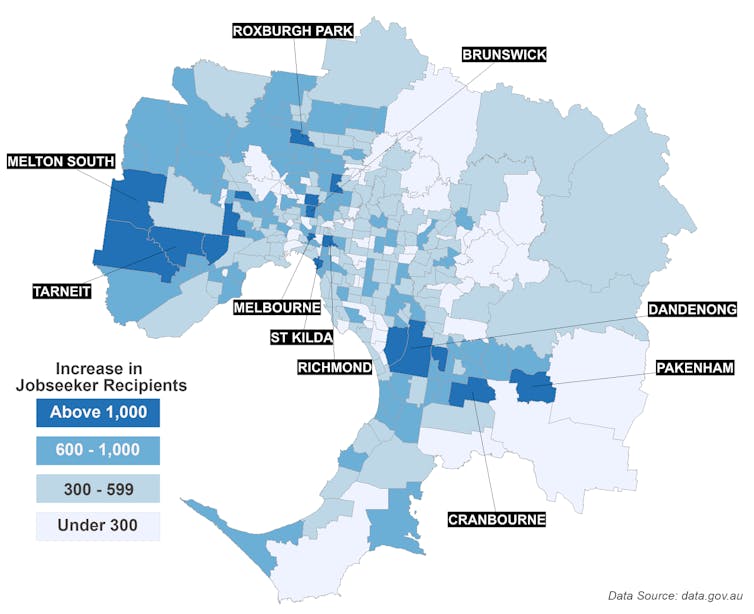

Map of JobSeeker increases indicating pandemic impacts on employment across Melbourne.

Map of JobSeeker increases indicating pandemic impacts on employment across Melbourne.

Read more: Coronavirus puts casual workers at risk of homelessness unless they get more support

In Melbourne increases in unemployment are concentrated in inner-city suburbs like Brunswick and St Kilda. This reflects the loss of jobs for young people in hospitality and retail.

Job losses have also occurred in working-class areas such as Brimbank, Melton and Hume. These losses reflect the impact of shutdowns in the processing, manufacturing and transport sectors.

It is predicted it will take some time for earnings to return to pre-COVID levels. This means renters who have not been able to get jobs will once again be in dire rental stress in most capital cities when the Coronavirus Supplement cuts out in January 2021.

What about household savings?

The Finder Consumer Sentiment Tracker shows household savings have temporarily increased. But it is difficult to assess how much reserve people on JobSeeker payment have been able to lay down, relative to the loss of normal earnings. Any optimism on this count needs to be tempered by the observation that the Coronavirus Supplement did not start until late April and early May — five to six weeks after the job losses started.

Our modelling shows that even during the temporary tapering down of the supplement until January 2021, there will be a rental crisis in cities like Melbourne. These findings can be extrapolated to other capital cities and the scenario will be worse in Sydney.

Cutting the JobSeeker supplement is risky policy because the labour market has not “snapped back”. People who depend on unemployment payments will now face the same problem of rental stress as those on NewStart experienced before the pandemic. But this stress will be more widespread than before. This underscores the need to develop policy that counters the risk of rental stress.

Read more: If we realised the true cost of homelessness, we'd fix it overnight

Authors: Simone Casey, Research Associate, Future Social Service Institute, RMIT University