Cladding fires expose gaps in building material safety checks. Here's a solution

- Written by Kevin Argus, Lecturer, Marketing & Design Thinking, RMIT University

A fire at the Neo 200 apartment building in Spencer Street, Melbourne, on Monday highlighted the risk to human safety from flammable cladding and other non-conforming building products. Building quality and safety are compromised when there is no transparency about the products used.

Our experimental research project suggests a solution that uses sensor technology and artificial intelligence. Finding such a solution to ensure unsafe and substandard products are detected and prevented from being used in buildings is critical, given the scale of the problem in Australia.

In 2014, a similar cladding fire spread across multiple levels of the Lacrosse Tower in Melbourne’s Docklands. This led to an initial audit by the Victorian Building Authority.

In 2017, after 72 people died in the Grenfell cladding fire in London, the Victorian Cladding Taskforce conducted another audit. It found at least 1,400 buildings contained cladding that was non-conforming to Australian standards and/or non-compliant with government safety regulations. Its interim report concluded:

The Victorian Cladding Taskforce has found systems failures have led to major safety risks and widespread non-compliant use of combustible cladding in the building industry across the state.

Read more: Grenfell: a year on, here's what we know went wrong

How could this happen?

The taskforce noted 12 reasons for non-compliant use of cladding. From a systems perspective, these can be categorised as:

- incentive to substitute products driven by cost

- no reliable means of independently verifying product certification

- product labelling cannot be verified to detect fraudulent or misleading information

- products cannot reliably be verified as being the same as those approved (and used)

- on-site inspections are unreliable or do not take place.

Essentially, the taskforce identified a problem with the system of verifying products’ conformance to standards and compliance with government regulation.

Substandard products can be found across a range of materials used in the building sector. These include steel, copper, electrical products, glass, aluminium and engineered wood. For example, the Senate inquiry into non-conforming products found:

The ACCC [Australian Competition and Consumer Commission] advised that electrical retailers and wholesalers have recalled Infinity and Olsent-branded electrical cables, warning that ‘physical contact with the recalled cables could dislodge the insulation and lead to electric shock or fires’.

The taskforce estimated over 22,000 homes were affected. It estimated the cost of the recall and replacement at A$80 million.

Read more: Reach for the sky: why safety must rule as tall buildings aim higher

So how can technology help?

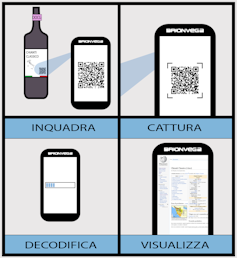

A QR code can tell you about this bottle of Chianti and, by matching against supply chain data, can be used to verify that the wine is genuine.

Andrea Pavanello, Milano/WIkimedia, CC BY-SA

A QR code can tell you about this bottle of Chianti and, by matching against supply chain data, can be used to verify that the wine is genuine.

Andrea Pavanello, Milano/WIkimedia, CC BY-SA

Similar problems have existed in other industries. In the wine export industry, sensor technology has been used to detect fraudulent products in our biggest market, China. This involves scanning QR codes on bottle labels to identify the manufacturer, the batch and other product details that authenticate wine products.

Scanning technology, involving complex data-matching across different data platforms, is used daily – when we use credit cards, for example. The building industry has embraced some excellent systems to collect data of importance such as building information modelling (BIM). However, BIM does not verify authenticity of products.

In the the case of flammable cladding, data verification to solve the use of non-conforming products is housed across a number of authorities, manufacturers and industry associations. Collaboration is needed to design a system to solve the problem. The data should be collected and stored in a manner that enables secure access by a digital verification system.

What features does the system need to have?

Our research focus has been on designing a system based on criteria informed by industry innovators and stakeholders. The system must be able to:

- collect and match product data in real time

- verify non-conforming and non-compliant products in real time

- maintain integrity of labelling

- store data securely so all stakeholders can verify the status of the building, including architects, builders, site managers, inspectors, owners, investors, insurers and financiers

- trace data (and composition) throughout the product life-cycle, to predict maintenance, recovery and repurposing.

The system we suggest uses two elements, sensor technology and artificial intelligence, to do all this.

Technology to solve the problem of tracking and validating building product safety is being developed.How does the system work?

A mobile app that can scan QR codes or “building material passports” is being developed in Europe. The label will hold relevant compliance data of the assembled product and its component parts. This includes building code compliance, and relevant assessments and certifications.

The product’s QR code can be scanned at any time along the supply chain and throughout the life of the building. This then enables its status to be verified via data matching.

Linking to a platform that uses artificial intelligence (AI) solves the problem of ensuring compliance with government regulation. CSIRO Data 61 has developed an AI software tool that enables regulation to be coded using AI algorithms to accurately determine compliance. We are working with Data 61 to test Australian regulation and ensure transparency for all.

The solution is designed to plug into existing technology solutions, such as BIM and Matrack, to trace the movement of products along the supply chain and throughout the building’s life-cycle.

Authors: Kevin Argus, Lecturer, Marketing & Design Thinking, RMIT University