Queensland's floods are so huge the only way to track them is from space

- Written by Linlin Ge, Professor, UNSW

Many parts of Queensland have been declared disaster zones and thousands of residents evacuated due to a 1-in-100-year flood. Townsville is at the epicentre of the “unprecedented” monsoonal downpour that brought more than a year’s worth of rain in just a few days, and the emergency is far from over with yet more torrential rain expected.

Such monumental disruption calls for emergency work to safeguard crucial infrastructure such as bridges, dams, motorways, railways, power substations, power lines and telecommunications cables. In turn, that requires accurate, timely mapping of flood waters.

For the first time in Australia, our research team has been monitoring the floods closely using a new technique involving European satellites, which allows us to “see” beneath the cloud cover and map developments on the ground.

Read more: Floods don't occur randomly, so why do we still plan as if they do?

Given that the flooding currently covers a 700km stretch of coast from Cairns to Mackay, it would take days to piece together the big picture of the flood using airborne mapping. What’s more, conventional optical imaging satellites are easily “blinded” by cloud cover.

But a radar satellite can fly over the entire state in a matter of seconds, and an accurate and comprehensive flood map can be produced in less than an hour.

Our new method uses an imaging technology called “synthetic aperture radar” (SAR), which can observe the ground day or night, through cloud cover or smoke. By combining and comparing SAR images, we can determine the progress of an unfolding disaster such as a flood.

In simple terms, if an area is not flooded on the first image but is inundated on the second image, the resulting discrepancy between the two images can help to reveal the flood’s extent and identify the advancing flood front.

To automate this process and make it more accurate, we use two pairs of images: a “pre-event pair” taken before the flood, and a “co-event pair” made up of one image before the flood, and another later image during the flooding.

The European satellites have been operated strategically to collect images globally once every 12 days, making it possible for us to test this new technique in Townsville as soon as flooding occurs.

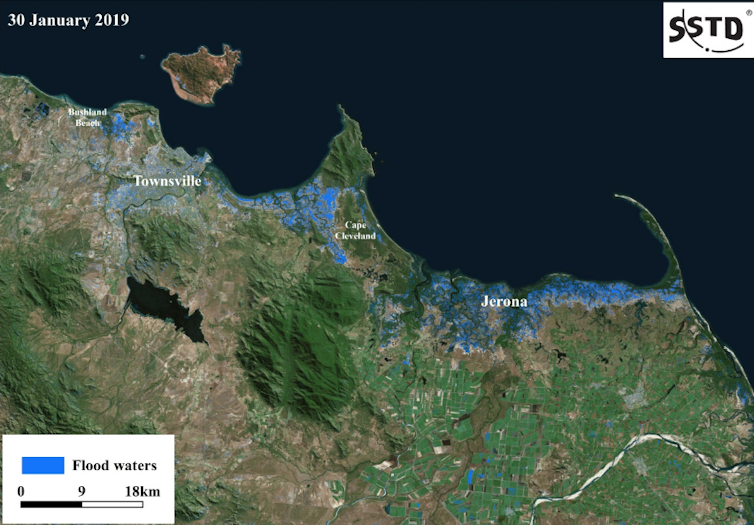

To monitor the current floods in Townsville, we took the pre-event images on January 6 and January 18, 2019. The co-event pair was collected on January 18 and January 30. These sets of images were then used to generate the accurate and detailed flood map shown below.

The image comparisons can all be done algorithmically, without a human having to scrutinise the images themselves. Then we can just look out for image pairs with significant discrepancies, and then concentrate our attention on those.

Satellite flood mapping along the Queensland coast, compiled using images from the European radar satellite Sentinel-1A.

European Space Agency/Smart Spatial Technology Development Laborator (SSTD), UNSW, Author provided

Satellite flood mapping along the Queensland coast, compiled using images from the European radar satellite Sentinel-1A.

European Space Agency/Smart Spatial Technology Development Laborator (SSTD), UNSW, Author provided

Read more: Planning for a rainy day: there's still lots to learn about Australia's flood patterns

Our technique potentially avoids the need to monitor floods from airborne reconnaissance planes – a dangerous or even impossible task amid heavy rains, strong wind, thick cloud and lightning.

This timely flood intelligence from satellites can be used to switch off critical infrastructure such as power substations before flood water reaches them.

Authors: Linlin Ge, Professor, UNSW