MYEFO reveals billions more in revenue, $9 billion in fresh election tax cuts

- Written by Emil Jeyaratnam, Data + Interactives Editor, The Conversation

Higher than expected company tax revenue and lower than expected spending has boosted the budget’s bottom line by A$14 billion over next four years, allowing it to forecast cumulative surpluses of A$30.4 billion, double what it predicted in the budget in May.

Modestly improved surpluses

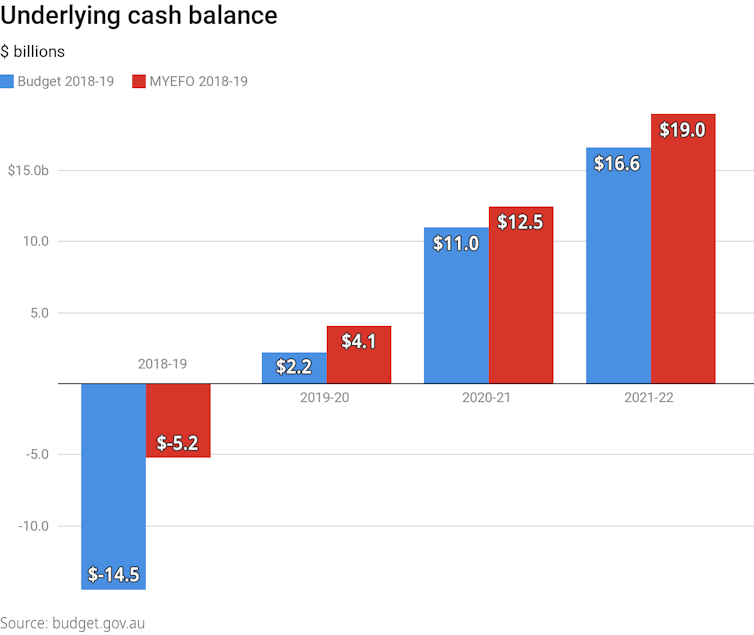

The mid-year budget update cuts the projected deficit for 2018-19 from a May estimate of A$14.5 billion to A$5.2 billion.

The surplus forecast for 2019-20 climbs from A$2.2 billion to A$4.1 billion. By 2021-22 the surplus is forecast to be A$19 billion, up from A$16.6 billion.

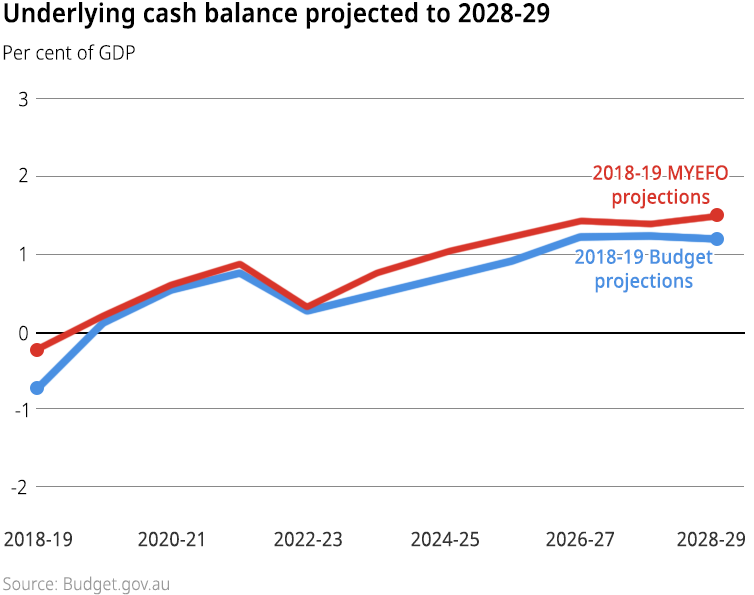

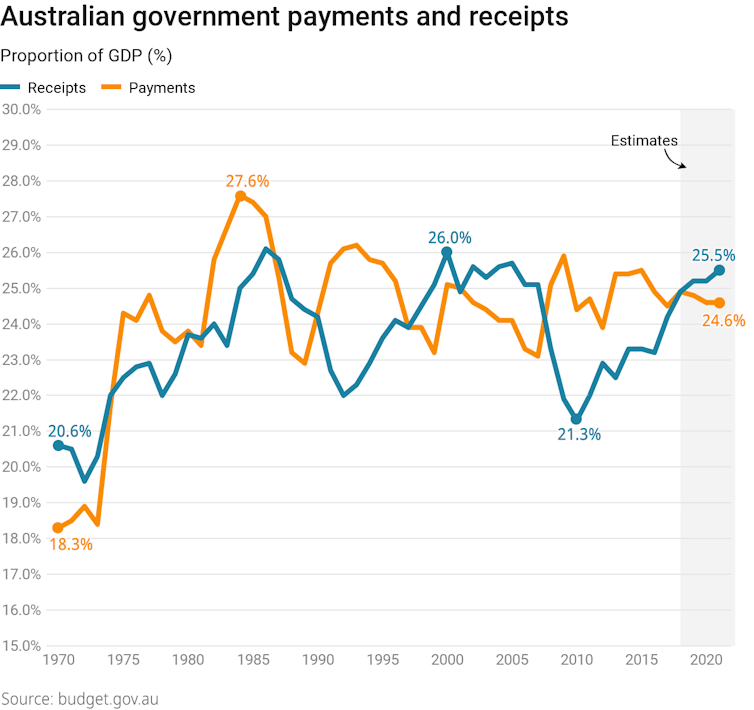

The surplus won’t reach the government’s long-term target of 1% of gross domestic product until 2025-26, and in projections out to 2028-29 is not forecast to climb much above it as the budget hits the Coalition’ self-imposed tax “speed limit” of 23.9% of GDP.

The surplus won’t reach the government’s long-term target of 1% of gross domestic product until 2025-26, and in projections out to 2028-29 is not forecast to climb much above it as the budget hits the Coalition’ self-imposed tax “speed limit” of 23.9% of GDP.

$9 billion in unannounced tax cuts

The budget boost would have been much bigger were it not for more than A$9 billion in “decisions taken but not announced”, almost all of which are revenue decisions, presumably extra election tax cuts, worth A$2.5 to A$3.7 billion per year.

The budget papers say these are decisions taken since the May budget, and are either not for publication or haven’t yet been made public.

Read more:

Monday's MYEFO will look good, but it will set the budget up for awful trouble down the track

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg confirmed that the government had taken decisions to do with tax, but said it would announce them at a time of its choosing rather than int he budget update.

It reserved the right to take other tax and spending decisions in the leadup to the election, some of which would be revealed in the 2019-20 budget, to be delivered in April rather than in May to allow an election in May.

Downgraded wage growth

Although the Treasury has revised up its estimates for revenue and revised down its estimates of unemployment, expecting the rate to fall to 5% by June 2019 and stay there, it has shaved 0.25 percentage points off its estimates for wage growth.

It now expects wages to grow by 2.5% in the year to June 2019 (down from 2.75%) and 3% in 2019-20 (down from 3.25%). In future years, it expects wage growth of 3.5%.

$9 billion in unannounced tax cuts

The budget boost would have been much bigger were it not for more than A$9 billion in “decisions taken but not announced”, almost all of which are revenue decisions, presumably extra election tax cuts, worth A$2.5 to A$3.7 billion per year.

The budget papers say these are decisions taken since the May budget, and are either not for publication or haven’t yet been made public.

Read more:

Monday's MYEFO will look good, but it will set the budget up for awful trouble down the track

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg confirmed that the government had taken decisions to do with tax, but said it would announce them at a time of its choosing rather than int he budget update.

It reserved the right to take other tax and spending decisions in the leadup to the election, some of which would be revealed in the 2019-20 budget, to be delivered in April rather than in May to allow an election in May.

Downgraded wage growth

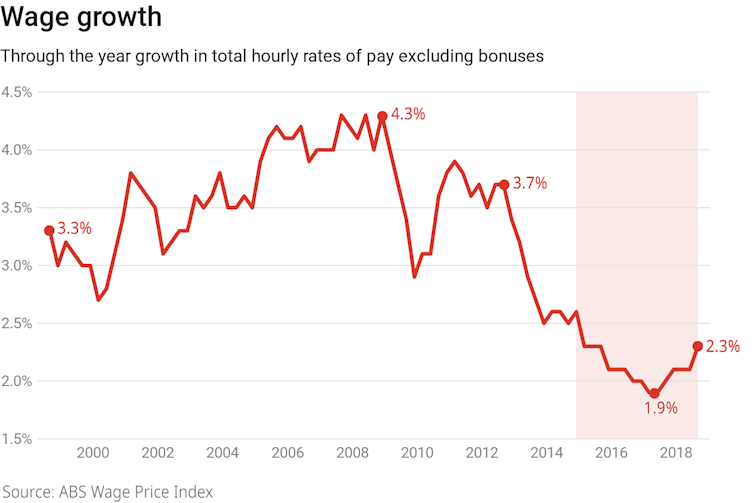

Although the Treasury has revised up its estimates for revenue and revised down its estimates of unemployment, expecting the rate to fall to 5% by June 2019 and stay there, it has shaved 0.25 percentage points off its estimates for wage growth.

It now expects wages to grow by 2.5% in the year to June 2019 (down from 2.75%) and 3% in 2019-20 (down from 3.25%). In future years, it expects wage growth of 3.5%.

Addressing the downgrade, Mr Frydenberg said weaker than expected wage growth appeared to be part of a worldwide phenomenon, “not unique to us”.

Wage growth for the year to September was 2.3%. the highest since 2015. The statement said anecdotal evidence from Treasury’s business liaison program pointed to “skills shortages and wage pressures in some sectors of the economy, consistent with a tightening labour market”.

Weaker consumer spending, economic growth

Growth in consumer spending has also been revised down, from 2.75% in 2018-19 to 2.5%. It is expected to climb back to 3% in 2019-20.

The statement revises down the government’s forecast of economic growth in 2018-19 from 3% to 2.75%, in part because of the Queensland drought, but predicts growth of 3% in 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22, a touch higher than the Treasury’s estimate of long-term sustainable growth which is a few notches below 3%.

But debt has peaked and is headed down

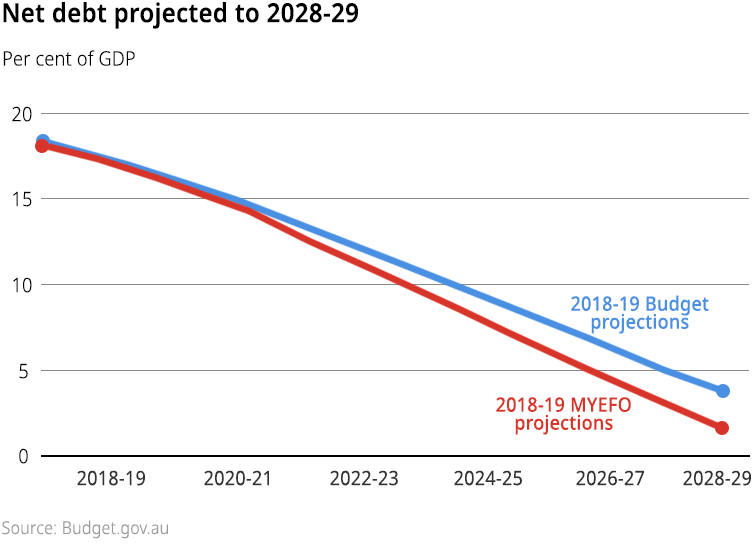

The updated figures show net debt has already peaked as a proportion of GDP and will fall faster than previously expected, in line with higher surpluses, sliding over from 18.2% of GDP to 1.5% over the decade to 2028-29.

Addressing the downgrade, Mr Frydenberg said weaker than expected wage growth appeared to be part of a worldwide phenomenon, “not unique to us”.

Wage growth for the year to September was 2.3%. the highest since 2015. The statement said anecdotal evidence from Treasury’s business liaison program pointed to “skills shortages and wage pressures in some sectors of the economy, consistent with a tightening labour market”.

Weaker consumer spending, economic growth

Growth in consumer spending has also been revised down, from 2.75% in 2018-19 to 2.5%. It is expected to climb back to 3% in 2019-20.

The statement revises down the government’s forecast of economic growth in 2018-19 from 3% to 2.75%, in part because of the Queensland drought, but predicts growth of 3% in 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22, a touch higher than the Treasury’s estimate of long-term sustainable growth which is a few notches below 3%.

But debt has peaked and is headed down

The updated figures show net debt has already peaked as a proportion of GDP and will fall faster than previously expected, in line with higher surpluses, sliding over from 18.2% of GDP to 1.5% over the decade to 2028-29.

Government receipts are expected to climb from 24.9% of GDP to 25.5% by 2021-22. Payments are expected to fall from 24.9% of GDP to 24.6%.

Mr Frydenberg said the Coalition had kept average real spending growth at 1.9 per cent per year, well below Labor’s 4% over six years which included the global financial crisis.

Government receipts are expected to climb from 24.9% of GDP to 25.5% by 2021-22. Payments are expected to fall from 24.9% of GDP to 24.6%.

Mr Frydenberg said the Coalition had kept average real spending growth at 1.9 per cent per year, well below Labor’s 4% over six years which included the global financial crisis.

Finance Minister Mathias Cormann said recurrent spending had fallen below recurrent revenue for the first time in more than a decade.

Recurrent spending excludes spending on long term investments in things such as road and rail infrastructure.

He said all new spending since the May budget had been offset by spending cuts elsewhere.

No firm commitment on fiscal discipline

Asked to give whether he felt bound by a commitment in the budget papers to bank rather than spend improvements to the budget’s bottom line due to changes in the economy, Mr Cormann is it was “a matter of balancing priorities”.

The imperative to cut tax in order to keep it below the government’s self imposed speed limit might conflict with the commitment to devote extra tax takings to improving the bottom line.

Finance Minister Mathias Cormann said recurrent spending had fallen below recurrent revenue for the first time in more than a decade.

Recurrent spending excludes spending on long term investments in things such as road and rail infrastructure.

He said all new spending since the May budget had been offset by spending cuts elsewhere.

No firm commitment on fiscal discipline

Asked to give whether he felt bound by a commitment in the budget papers to bank rather than spend improvements to the budget’s bottom line due to changes in the economy, Mr Cormann is it was “a matter of balancing priorities”.

The imperative to cut tax in order to keep it below the government’s self imposed speed limit might conflict with the commitment to devote extra tax takings to improving the bottom line.

Authors: Emil Jeyaratnam, Data + Interactives Editor, The Conversation