David Crisafulli will lead the first LNP government in Queensland in a decade. Who is he?

- Written by Pandanus Petter, Research Fellow School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University

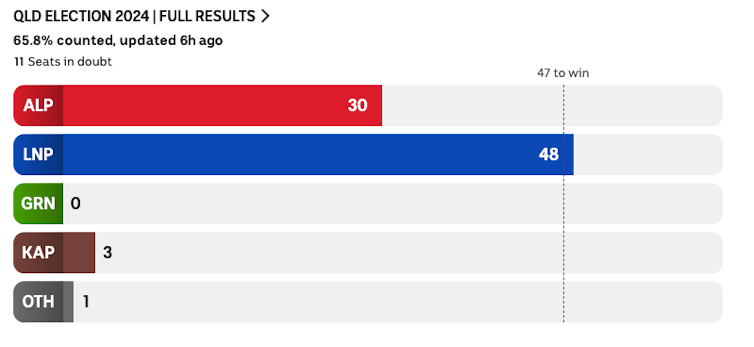

David Crisafulli, leader of the centre-right Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP), will be Queensland’s 41st Premier. The party will form majority government for the first time since 2012.

Late Saturday night, Crisafulli claimed a victory of “hope over fear”, following a campaign dominated by messaging around youth crime, cost of living, housing and health crisises.

Although earlier polling was projecting a landslide to the LNP, Steven Miles’ three-term Labor party were able to narrow this lead in the final week of campaigning.

While there will be a change of government, the result wasn’t as decisive as many expected. As the vote counts trickled in on election night, they revealed a fragmented picture of who Queenslanders want in their parliament.

Read more: LNP wins Queensland election, likely with a clear majority

LNP success in the regions

Miles campaigned vigorously on bread and butter, cost of living issues while promising more state involvement and regulation in housing, energy retail and petrol stations.

This looks to have played well in their heartland seats in Brisbane, Ipswich and Logan where they have likely returned South Brisbane and Ipswich West to the fold. Labor lost the former to The Greens in 2020 and the latter to the LNP in a by-election earlier in 2024.

Despite this, with their laser focus on youth crime, the LNP made strong gains across the state, particularly on the North and central Queensland coasts.

They even took Mackay, a seat Labor has held for more than a century.

The LNP harmonised their heavy focus on crime with the selection of candidates. Some were high-profile victims of crime campaigners (such as in Capalaba, just outside of Brisbane). Others had a background in law enforcement.

How did the minor parties fare?

While the primary vote for the Greens increased modestly, they fell short of the election results they had hoped for. Having campaigned hard in four inner Brisbane seats in particular, the party has failed to pick up any seats so far, though they’re ahead in Maiwar.

Despite their efforts to pick up more seats in Queensland’s north, the parliament will likely continue on with a contingent of three or four Katter’s Australian Party MPs.

Popular independent Sandy Bolton was reelected in Noosa, while One Nation failed to secure a seat after running a candidate in all 93 electorates.

But the LNP will govern with a majority. It is one Crisafulli last night said they would use with “humility and decency”, in order to “govern for a long time”.

This was likely alluding to possible lessons learned from the LNP’s short-lived success last time around.

But it was also foreshadowing challenges he will face as a leader.

Who’s the new premier?

Like many politicians, Crisafulli will point to his early upbringing as teaching valuable lessons along his pathway to the premiership.

The 45-year-old was born in Ingham in North Queensland, the son and grandson of Italian migrants who run a successful sugarcane farm.

In his maiden speech in 2012, he attributed his success to his upbringing on the farm, the discipline he learned at local Catholic primary and secondary schools and the skills acquired working as a journalist during and after his days at James Cook University (where he was also known for competitive spaghetti eating).

He can claim to be able to understand the needs of rural constituents and those in the far north, who often feel neglected compared to the more densely populated south-east.

Despite this, his later career shows that he’s not tied down to that rural identity. It also shows he can’t claim to be an amateur politician.

Although he wasn’t involved in student politics, his political education began early as a media advisor for former Howard Minister Ian McDonald.

He demonstrated energy and ambition which have remained hallmarks of his career when he took a successful tilt at usually Labor-dominated Townsville politics, becoming the youngest ever councillor in 2004 and deputy mayor in 2008.

He joined state parliament in the bellwether seat of Mundingburra as part of Campbell Newman’s 2012 wipeout of Labor.

However, his time as a cabinet minister and high public profile weren’t enough to save him from a bitter exit from parliament when the electorate swung back towards Labor in 2015.

After reinventing himself as a Gold Coast based business consultant, he began his ascent anew by successfully defeating the incumbent in the safe LNP seat of Broadwater.

After the party lost the 2020 election, Crisafulli took over the party leadership.

He remained constantly on the move, unusually not residing permanently in his electorate but instead travelling the state extensively.

Crisafulli has focused on keeping public attention on crises (so-called or real) in youth crime (even promising to resign if he couldn’t quickly quash crime rates).

He also campaigned on health services and home-ownership and cost of living.

In aid of this goal, he mirrored many Labor party commitments to cost-of-living relief, such as cheaper public transport. Unusually, Crisafulli even agreed to honour their budget commitments sight unseen.

But on more controversial issues of interest to the party’s conservative base, he’s shown a tendency to try to avoid being nailed down.

This was most clear on the issue of abortion. Late in the campaign, Crisafulli said he supported “a woman’s right to choose”, but hasn’t ruled out a conscience vote on the subject.

Otherwise, he has only moved the party decisively to the right when he could claim to be following public opinion. For example, he abandoned bipartisan support for a Pathway to Treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders after the unsuccessful Voice referendum.

Interestingly, Crisafulli has shown a willingness to disagree with his federal counterparts on nuclear energy.

Given he’s staked his leadership and credibility on addressing thorny problems in housing, health, crime and cost of living, he may have to take some big political risks.

Given the voters of Queensland have gifted him a majority, which in Queensland’s parliament comes with few restrictions on power, how well he’ll manage to avoid the mistakes of the Newman era remains to be seen.

Authors: Pandanus Petter, Research Fellow School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University