Scientists reviewed 7,000 studies on microplastics. Their alarming conclusion puts humanity on notice

- Written by Karen Raubenheimer, Senior Lecturer, University of Wollongong

It’s been 20 years since a paper in the journal Science showed the environmental accumulation of tiny plastic fragments and fibres. It named the particles “microplastics”.

The paper opened an entire research field. Since then, more than 7,000 published studies have shown the prevalence of microplastics in the environment, in wildlife and in the human body.

So what have we learned? In a paper released today, an international group of experts, including myself, summarise the current state of knowledge.

In short, microplastics are widespread, accumulating in the remotest parts of our planet. There is evidence of their toxic effects at every level of biological organisation, from tiny insects at the bottom of the food chain to apex predators.

Microplastics are pervasive in food and drink and have been detected throughout the human body. Evidence of their harmful effects is emerging.

The scientific evidence is now more than sufficient: collective global action is urgently needed to tackle microplastics – and the problem has never been more pressing.

Microplastic pollution is the result of human actions and decisions. We created the problem – and now we must create the solution.

Tiny particles, huge problem

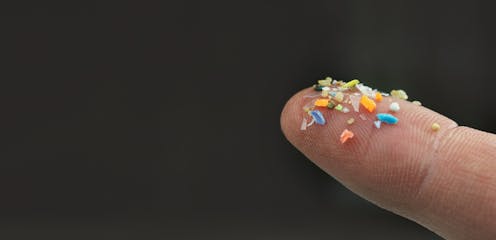

Microplastics are generally accepted as plastic particles 5mm or less in one dimension.

Some microplastics are intentionally added to products, such as microbeads in facial soaps.

Others are produced unintentionally when bigger plastic items break down – for example, fibres released when you wash a polyester fleece jacket.

Studies have identified some of the main sources of microplastics as:

- cosmetic cleansers

- synthetic textiles

- vehicle tyres

- plastic-coated fertilisers

- plastic film used as mulch in agriculture

- fishing rope and netting

- “crumb rubber infill” used in artificial turf

- plastics recycling.

Science hasn’t yet determined the rate at which larger plastics break down into microplastics. They are also still researching how quickly microplastics become “nanoplastics” – even smaller particles invisible to the eye.