Why knock down all public housing towers when retrofit can sometimes be better?

- Written by Trivess Moore, Associate Professor, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University

The Victorian government is planning Australia’s largest urban renewal project. The plan is to knock down and rebuild 44 large public housing towers in Melbourne. The government says these towers, built in the 1960s and ’70s, are no longer fit for purpose and will cost more to maintain and upgrade than to replace.

Rebuilding will allow 20,000 more people to live on these sites. However, most of the extra housing will be for private renters or owners. It will not add much more public or affordable housing.

Rebuilding involves breaking up public housing communities. Many tenants have already been forcibly displaced. Removing stock from the system to make way for future housing reduces the capacity to house people in need amid a housing crisis.

Tearing down so much concrete and other materials and rebuilding in a carbon-constrained world also raises concerns about the public value for money and the loss of embodied carbon in these old buildings. The materials and energy needed to erect a new building create a lot of greenhouse gas emissions. Construction produces almost a fifth of Australia’s emissions.

Some industry experts say the housing towers are structurally sound. They and other sustainability researchers argue that retrofits can bring the buildings up to modern standards.

This approach would improve thermal comfort, cut energy bills and produce fewer emissions. Some retrofitted buildings could have half the embodied energy of newly built ones. And communities could largely remain in place while the work is done.

Public housing complexes across Australia face similar renewal proposals. In each case, there are valid questions about the balance of public and private benefit.

So, how should decisions on public housing account for environmental, social and economic costs and benefits for all the people and interests involved? We draw on our recent research on life-cycle impacts and public housing tenant relocations to answer this question. Our research shows decisions on each tower that are underpinned by a proper process – one that considers all the evidence – could go either way: demolish and rebuild, or retrofit.

What are the options for ageing buildings?

Broadly, there are three options for older high-rise housing:

- maintain

- retrofit

- knock down and rebuild.

The first option is increasingly unviable. This is because of the urgent need to decarbonise our building stock and the impacts of decades of under-maintenance on such buildings.

In 2017, the Auditor-General’s Office found the Victorian government lacked the capacity to “reliably assess the condition of its stock, and consequently whether it is deteriorating at a rate faster than it is ageing”. Maintaining the current stock, while not knowing its condition, would require a massive policy shift and repair effort.

That leaves us with retrofits or demolition and rebuilding. The government has chosen the third option for all 44 towers.

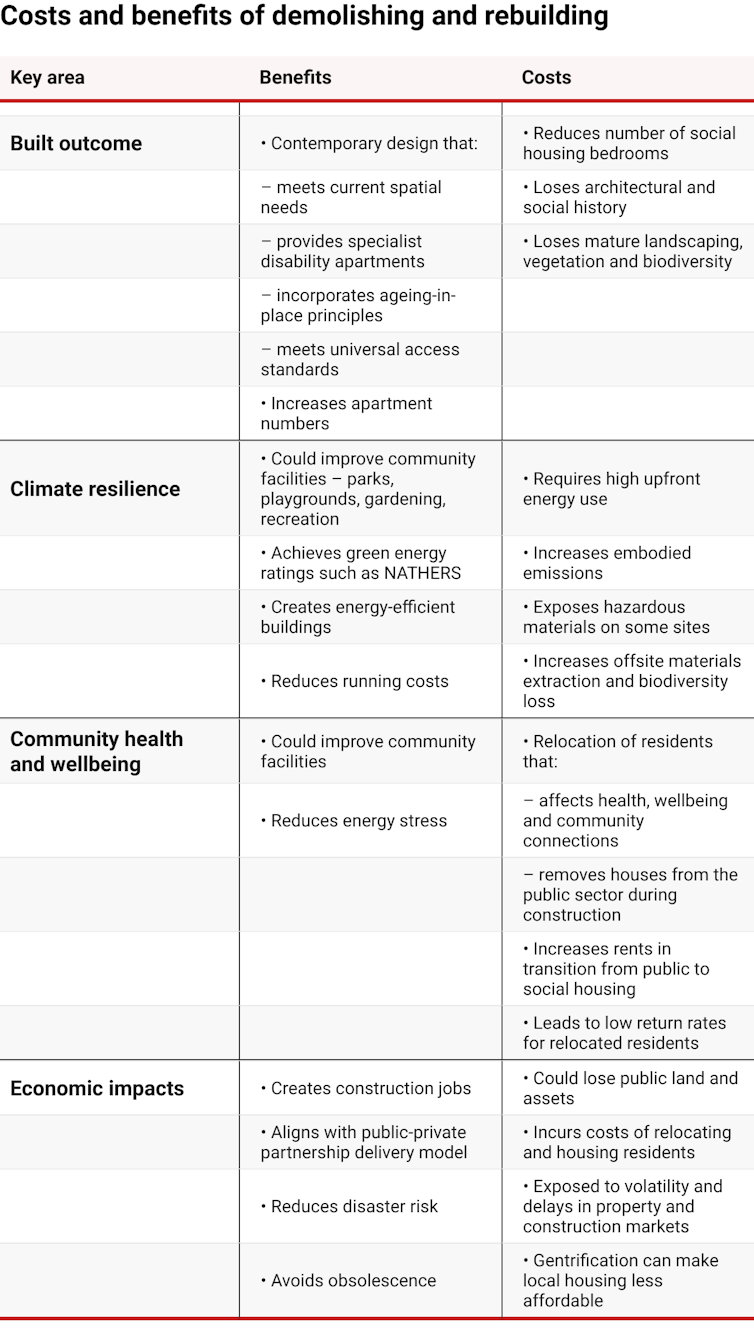

The table below sums up the broader costs and benefits of demolition and rebuilding.