Throwing things on stage is bad concert etiquette – but it's also not a new trend

- Written by Timothy McKenry, Professor of Music, Australian Catholic University

The recent spate of incidents where objects have been thrown at musicians by people who paid to see them perform has generated comment, consternation and condemnation on media both mainstream and social.

One recent case involved liquid being thrown on stage during a performance by American rapper Cardi B. The singer retaliated by throwing her microphone into the crowd. Media accounts suggest the incident has resulted in a police complaint filed by someone in the audience.

With mobile phones, soft toys, flower arrangements and even cremains raining down on the world’s most famous musicians, commentators and celebrities alike predict injury and interruption are inevitable.

Why has concert etiquette been forgotten?

“Have you noticed how people are, like, forgetting fucking show etiquette at the moment?” pointed out singer Adele recently.

Some scholars see this trend as a consequence of the suspension of live performances during COVID-19. The idea being that audiences – particularly those made up of large crowds – are out of practice when it comes to concert etiquette.

Others suggest the behaviour represents an attempt by fans to interact with the performers they love and achieve status within fan communities through viral social media content.

It’s also possible we’ve overstated this phenomenon and that ravenous media, hungry for stories and scandal, are interpreting unrelated events as a trend. Motivation, for example, differs markedly.

The devoted fan who threw a rose at Harry Styles is clearly not in the same category as the man who hit Bebe Rehxa in the face with his mobile phone “because it would be funny”.

Throwing things historically

Additionally, none of these incidents are without historical precedent.

Whether a bouquet of flowers tossed to an opera singer to communicate delight at their performance or a story of rotten fruit hurled at performers to convey disdain at a disastrous opening night, history shows throwing things at live performances is nothing new.

Just as the social status of musicians has changed over time (in the late 18th century top-rank musicians gradually transitioned from servants to celebrities), so too has concert etiquette. Concert etiquette is a manifestation of the social contracts that exist between musicians and their audiences. These are in a constant state of flux and differ wildly over time, place, style and genre.

For example, were I to attend the opera this weekend and spend the evening chatting to those around me, tapping my feet and shouting across the auditorium and at the performers, I’d be committing a major breach of etiquette. Indeed, I would quickly be escorted out. Were I to display these same behaviours in a mid-18th-century Parisian opera house, I would fit right in.

Read more: I'm going to a classical music concert for the first time. What should I know?

Flowers and souvenirs and mania

In the same way, throwing items like flowers, love notes and handkerchiefs at musicians, in some settings at least, has transitioned from aberrant to ordinary.

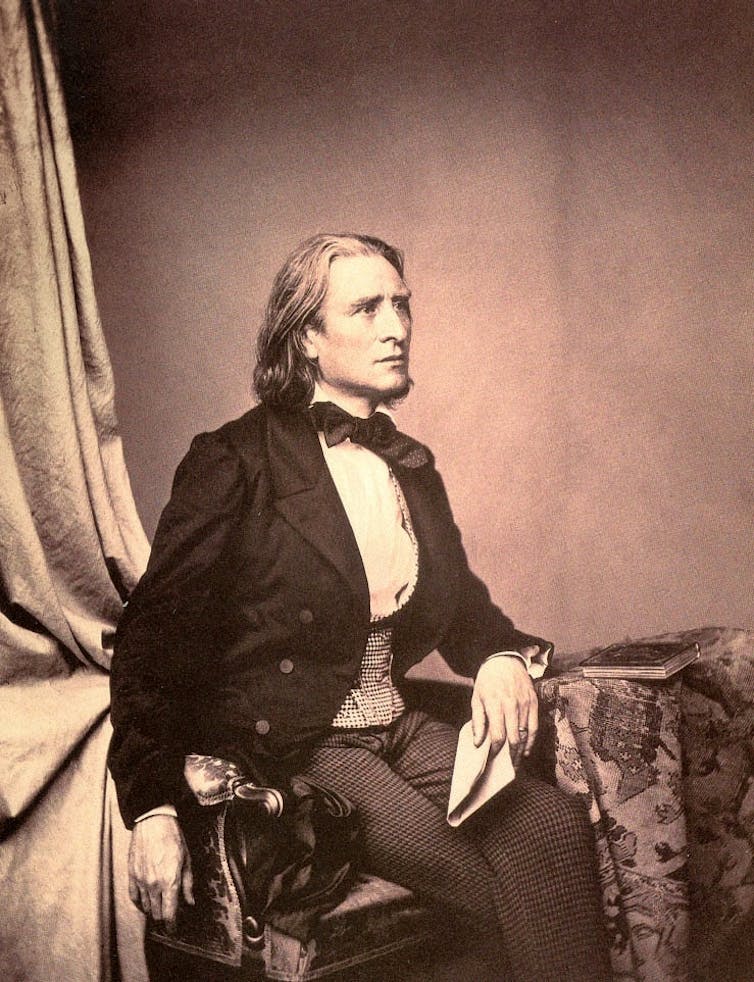

Some 180 years before fans were casting flowers at Harry Styles, the composer and pianist Franz Liszt was the object of fanatical adoration. His 1841-42 tour of Germany saw crowds of mostly women shower him with flowers and other tokens, scramble for souvenirs, and throw themselves at his feet.

Soon dubbed “Lisztomania”, this collective reaction to a musician by an audience was a relatively new phenomenon and one that was pathologised and criticised. In the words of the contemporary writer Heinrich Heine, Lisztomania was part of the “spiritual sickness of our time”.

Over time, these “manic” audience behaviours are, at least in some contexts, normalised and even celebrated. Beatlemania, for example, is generally understood as a watershed moment of cultural exuberance.

Changing concert etiquette

Musicians can be agents of change in relation to concert etiquette. Tom Jones, speaking in 2003, recalls the first time a fan threw underwear at him. While performing and perspiring at the Copacabana in New York, audience members handed him napkins. One woman threw underwear. Jones explains that a newspaper report, combined with his “leaning in” to the audience behaviour, created a phenomenon.

I would pick them up and play around with them, you know, because you learn that whatever happens on stage, you try to turn it to your advantage and not get thrown by it.

Jones’ engagement with this new mode of behaviour generated such a degree of positive reinforcement that it has become a clichéd fan behaviour employed in relation to numerous musicians. Jones came to view underwear throwing with a degree of ambivalence. He soon refrained from leaning in in the hope of moderating an act that became a parody of itself.

Throwing things at concerts goes both ways. Consider Adele firing a T-shirt gun into the crowd or Charlie Watts throwing his drumsticks to the audience after a performance. These acts are part of the performance and universally viewed as non-controversial.

Somewhat more controversial are mosh pits where performers sometimes even throw themselves into the audience. Recent research reveals a strict etiquette tied to this practice, founded on community and safety.

Finally, no concert etiquette ever permits throwing something hazardous or throwing something with the intent to harm. If these incidents do trend towards violence in service of notoriety on social media, live music will suffer.

Measures such as added security, physical barriers, airport style screening and even audience vetting will quickly become commonplace. Remember, celebrities like Liszt and Tom Jones aren’t the only agents of change. We can be too.

Authors: Timothy McKenry, Professor of Music, Australian Catholic University