Thirty years ago, American writer Susanna Kaysen published her memoir Girl, Interrupted. It tells the story of her two years inside McLean Hospital in Boston as a psychiatric patient.

She was admitted, aged 18, in 1967. A few months earlier, she had taken 50 aspirin in a state of despair. Late in the book, she reveals she had a sexual relationship with her male English teacher at school.

Kaysen was interviewed briefly by a doctor before she was admitted as a “voluntary” patient: a legal category used to indicate a person’s status in the institution. Despite what the term implies, “voluntary” doesn’t mean a patient can leave without the consent of their medical team, as Kaysen explains. People admitted as voluntary patients acknowledge their own need for treatment.

During Kaysen’s stay, she was treated with an antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, and received psychotherapy. In her memoir, the stories of other young women confined with her at McLean convey sympathetic and recognisable experiences of the institutional world and its regime.

Girl, Interrupted is one of the most famous memoirs of hospitalisation and mental illness. More recent interpretations describe it as a narrative of “trauma”.

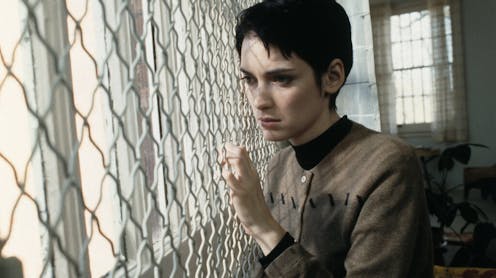

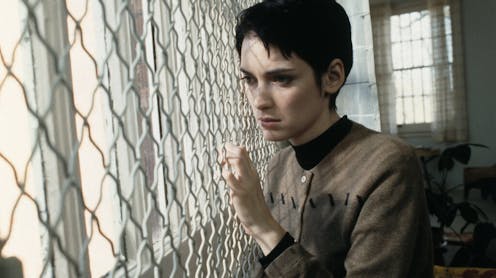

Susanna Kaysen was admitted as a ‘voluntary’ psychiatric patient aged 18, in 1967. She wrote about her experience in Girl, Interrupted.

Read more:

How can publishers support the authors of trauma memoirs, as they unpack their pain for the public? New research investigates

‘Mad’ or refusing to conform?

Kaysen did not anticipate the book’s reception at the time of its publication in 1993. It seemed to open readers up to tell their own stories, and they wrote to her from many places around the world to tell her about their hospitalisation. Looking back in a new edition published this year by Virago Books, she writes “it was surprising to me how many people had been in a mental hospital or had what used to be called a nervous breakdown”.

When it appeared, her book was widely reviewed as “funny”, “wry”, “piercing” and “frightening”. Set out as a series of short vignettes, the book allowed readers the space to “insert themselves” into this story of human suffering.

Investigating whether she had ever really been “crazy” – or just caught up in an oppressive approach to girls whose lives strayed from expectations – likely meant possible personal exposure, admission of frailty, and fear of judgement for Kaysen.

Thirty years later, we have better understandings of trauma and of care for people with mental illness. So what can this book tell us now?

Kaysen had waited almost three decades after these experiences before sharing her story in the early 1990s. This may be one reason it resonated with readers. The book was published at a time when most large institutions had closed as part of a worldwide trend towards deinstitutionalisation. Many people were starting to talk more openly about their own episodes of mental illness and recalling periods of hospitalisation that were sometimes grim and harrowing.

By the 1990s, there was also much greater awareness of the uneven power relationships in psychiatric treatment. Women and girls, subject to gendered social expectations, have historically received different forms of medical and psychiatric treatment. Women have been described as “mad” for centuries when they refused to conform to gender norms.

The book – an account of adolescent turmoil, with girlhood at the centre – can tell us about the lived experiences of teenage girls who face interior struggles over their mental health and wellbeing. Published in 1993 about the events of the late 60s, its insights are enduringly relevant.

A controversial diagnosis

In 1993, The New York Times ran an article titled “A Designated Crazy” that explained Kaysen had hired a lawyer to access her patient clinical records, 25 years after being at McLean. These appear in the book.

Placed at intervals in the narrative, these notes show the objectifying medical practices of admission, collecting information and establishing a diagnosis. The information in these clinical pages is deeply personal. Sharing them is an act of resistance and defiance.

“Needed McLean for [the past] 3 years”“Profoundly depressed – suicidal”“Promiscuous … might get herself pregnant”“Ran away from home”“Living in a boarding house”

Kaysen’s father, an academic at Princeton, wrote these notes in April 1967.

In June 1967, the formal medical notes from her admitting doctor stated she had “a chaotic and unplanned life”, was sleeping badly, was immersed in “fantasy” and was isolated.

Kaysen was admitted as “depressed”, “suicidal” and “schizophrenic”, with “borderline personality disorder”.

While the psychiatric diagnoses used in the 1960s still exist, the borderline diagnosis is now controversial. Progressive psychologists and feminist psychologists are more likely to use the term “complex trauma”. Some of the other young women in the memoir had traumatic life experiences of sexual abuse and violence, which manifested as eating disorders and self harm.

Diagnostic labels have evolved over time. The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952. In 1967, the year of Kaysen’s committal, the DSM did not include “borderline personality disorder”, though the borderline concept had been theorised from the 1940s.

Read more:

Borderline personality disorder is a hurtful label for real suffering – time we changed it

McLean’s famous patients

We can also read the book as an exposé of the controlling world of psychiatric institutions for people in the 1960s. The vast majority of people with psychiatric conditions were confined in public institutions, in often overcrowded conditions. Abuses happened, and violence was common.

Kaysen had waited almost three decades after these experiences before sharing her story in the early 1990s. This may be one reason it resonated with readers. The book was published at a time when most large institutions had closed as part of a worldwide trend towards deinstitutionalisation. Many people were starting to talk more openly about their own episodes of mental illness and recalling periods of hospitalisation that were sometimes grim and harrowing.

By the 1990s, there was also much greater awareness of the uneven power relationships in psychiatric treatment. Women and girls, subject to gendered social expectations, have historically received different forms of medical and psychiatric treatment. Women have been described as “mad” for centuries when they refused to conform to gender norms.

The book – an account of adolescent turmoil, with girlhood at the centre – can tell us about the lived experiences of teenage girls who face interior struggles over their mental health and wellbeing. Published in 1993 about the events of the late 60s, its insights are enduringly relevant.

A controversial diagnosis

In 1993, The New York Times ran an article titled “A Designated Crazy” that explained Kaysen had hired a lawyer to access her patient clinical records, 25 years after being at McLean. These appear in the book.

Placed at intervals in the narrative, these notes show the objectifying medical practices of admission, collecting information and establishing a diagnosis. The information in these clinical pages is deeply personal. Sharing them is an act of resistance and defiance.

“Needed McLean for [the past] 3 years”“Profoundly depressed – suicidal”“Promiscuous … might get herself pregnant”“Ran away from home”“Living in a boarding house”

Kaysen’s father, an academic at Princeton, wrote these notes in April 1967.

In June 1967, the formal medical notes from her admitting doctor stated she had “a chaotic and unplanned life”, was sleeping badly, was immersed in “fantasy” and was isolated.

Kaysen was admitted as “depressed”, “suicidal” and “schizophrenic”, with “borderline personality disorder”.

While the psychiatric diagnoses used in the 1960s still exist, the borderline diagnosis is now controversial. Progressive psychologists and feminist psychologists are more likely to use the term “complex trauma”. Some of the other young women in the memoir had traumatic life experiences of sexual abuse and violence, which manifested as eating disorders and self harm.

Diagnostic labels have evolved over time. The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952. In 1967, the year of Kaysen’s committal, the DSM did not include “borderline personality disorder”, though the borderline concept had been theorised from the 1940s.

Read more:

Borderline personality disorder is a hurtful label for real suffering – time we changed it

McLean’s famous patients

We can also read the book as an exposé of the controlling world of psychiatric institutions for people in the 1960s. The vast majority of people with psychiatric conditions were confined in public institutions, in often overcrowded conditions. Abuses happened, and violence was common.

John Forbes Nash, whose life inspired the film A Beautiful Mind, was also a McLean patient.

Peter Badge

One distinction for those hospitalised at McLean in Boston, a private institution, was that it housed people whose families could afford the steep fees. Kaysen’s father had to declare his salary when he signed the paperwork. Famous patients included the mathematician John Forbes Nash (whose story was told in the film, A Beautiful Mind), and New England poets Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath in the late 1950s.

McLean’s own “biography” is the subject of another book. Gracefully Insane shows its reputation as housing sometimes idiosyncratic and wealthy people whose families wanted them to be hidden, fearful of the stigma of mental illness in the family.

Plath’s The Bell Jar fictionalises her hospitalisation at McLean in the 1950s, following a suicide attempt.

Doctor Gordon’s private hospital crowned a grassy rise at the end of a long, secluded drive that had been whitened with broken quahog shells. The yellow clapboard walls of the large house, with its encircling verandah, gleamed in the sun, but no people strolled on the green dome of the lawn.

John Forbes Nash, whose life inspired the film A Beautiful Mind, was also a McLean patient.

Peter Badge

One distinction for those hospitalised at McLean in Boston, a private institution, was that it housed people whose families could afford the steep fees. Kaysen’s father had to declare his salary when he signed the paperwork. Famous patients included the mathematician John Forbes Nash (whose story was told in the film, A Beautiful Mind), and New England poets Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath in the late 1950s.

McLean’s own “biography” is the subject of another book. Gracefully Insane shows its reputation as housing sometimes idiosyncratic and wealthy people whose families wanted them to be hidden, fearful of the stigma of mental illness in the family.

Plath’s The Bell Jar fictionalises her hospitalisation at McLean in the 1950s, following a suicide attempt.

Doctor Gordon’s private hospital crowned a grassy rise at the end of a long, secluded drive that had been whitened with broken quahog shells. The yellow clapboard walls of the large house, with its encircling verandah, gleamed in the sun, but no people strolled on the green dome of the lawn.

Like Kaysen, Plath’s character Esther Greenwood has been involved in sexual relationships with men that made her uneasy, affecting her confidence and sense of self. Skiing with Buddy Willard, she falls and breaks her leg: “you were doing fine”, someone says, “until that man stepped into your path”.

Later, floundering at college, she too is admitted by a male doctor acting on the advice of her mother: she has not slept, she is exhausted, she is not herself. He advises she needs shock therapy.

In her new biography of Plath, Red Comet, Heather Clark describes McLean in the 1950s as reliant on shock therapy and activities, rather than psychoanalysis and careful therapeutic interventions. It was reputedly only a “notch above” a public institution, though it had the veneer of being for elite residents.

Just a few years before Kaysen’s admission to McLean, Plath died by suicide in 1963, aged 30. The Bell Jar had been published one month earlier, under a pseudonym. By the late 1960s, teenage admissions were a focus for McLean’s doctors.

Did adolesence present a new challenge for families and authorities, making young women vulnerable to institutionalisation?

Like Kaysen, Plath’s character Esther Greenwood has been involved in sexual relationships with men that made her uneasy, affecting her confidence and sense of self. Skiing with Buddy Willard, she falls and breaks her leg: “you were doing fine”, someone says, “until that man stepped into your path”.

Later, floundering at college, she too is admitted by a male doctor acting on the advice of her mother: she has not slept, she is exhausted, she is not herself. He advises she needs shock therapy.

In her new biography of Plath, Red Comet, Heather Clark describes McLean in the 1950s as reliant on shock therapy and activities, rather than psychoanalysis and careful therapeutic interventions. It was reputedly only a “notch above” a public institution, though it had the veneer of being for elite residents.

Just a few years before Kaysen’s admission to McLean, Plath died by suicide in 1963, aged 30. The Bell Jar had been published one month earlier, under a pseudonym. By the late 1960s, teenage admissions were a focus for McLean’s doctors.

Did adolesence present a new challenge for families and authorities, making young women vulnerable to institutionalisation?

McLean Hospital’s famous patients included Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell, as well as John Forbes Nash and Susanna Kaysen.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

By naming 'Pennhurst', Stranger Things uses disability trauma for entertainment. Dark tourism and asylum tours do too

Psychiatry and romantic love

Revisiting Girl, Interrupted, I am struck by its raw and honest recognition of the way women have sometimes experienced relationships with men as inherently oppressive. The structures of psychiatry and romantic love intersect throughout this book.

Kaysen, like Plath, sees the family as a toxic institution. Male psychiatrists loom over both women, imposing in their authority to diagnose. “He looked triumphant”, wrote Kaysen of her doctor. “Doctor Gordon cradled his pencil like a slim, silver bullet”, wrote Plath.

Women writing about their own madness has a long history. American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) penned the story The Yellow Wallpaper in The New England Magazine in 1892. It tells the tale of a woman’s mental and physical exhaustion following childbirth.

Historians such as Elizabeth Lunbeck write about the way a “psychiatric persuasion” came to dominate thinking about gender in the early 20th century. Psychiatrists began to see everyday life difficulties – such as the changes experienced during adolescence – as signalling illness (we might say, pathologising “normal” responses to stressful events). The rise of psychiatric expertise paralleled their professional reactions to women (and men) who struggled with life.

In Australia, the history of “good and mad women” up to the 1970s by Jill Julius Matthews showed that women who experienced hospitalisation as a result of mental breakdown were perceived as having “failed” to meet the gendered expectations of them. Femininity and its constraints left some women unable to function or live authentic lives.

Institutions on film

Girl, Interrupted was released as a film by Columbia Pictures in 1999, with a cast of rising and established young actors, including Winona Ryder, Angelina Jolie and Brittany Murphy. It dramatised the interpersonal relationships inside the hospital described by Kaysen.

The film script was not only the perfect vehicle for an ensemble cast of these women. It was also another opportunity to make mental illness visible on the screen. Another page-to-screen adaptation in 1975, Milos Forman’s film of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, brought to life the dramatic environment of institutional control and violence personified by the character of Nurse Ratched.

Girl, Interrupted, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, emphasised resistance to institutional control.Girl, Interrupted’s screenplay surfaced different women’s experiences of abuse, neglect, trauma and violence to explain their behaviours and responses to institutional constraints.

Like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the film also emphasised the theme of resistance to institutional control. Patients hid pill medications under the tongue, broke into the hospital administration office to look at their case files, and found ways to circumvent the routines of institutional life. The film depicted the drama of group therapy, and the power dynamic between staff and patients.

Not everyone who was institutionalised reacted the same way to being in hospital.

Kaysen wrote:

For many of us, the hospital was as much a refuge as it was a prison. Though we were cut off from the world and all the trouble we enjoyed stirring up out there, we were also cut off from the demands and expectations that had driven us crazy.

A recent collaborative history of institutional care by Australian poet Sandy Jeffs and social worker Margaret Leggatt, Out of the Madhouse, challenges the idea of the institution as a place of alienation. Jeffs found community and solace at Larundel Hospital in Melbourne in the late 1970s and 1980s. However, the book also acknowledges this is not a universal response for institutionalised people.

Like Kaysen, people with lived experiences of mental illness and hospitalisation have found it therapeutic to write about their personal challenges. For some, it provides an opportunity to embrace the “mad” identity, to find empathy for others. And to create a new self out of the chaos of mental breakdown.

Authors: Catharine Coleborne, Professor of History, School Humanities, Creative Industries and Social Sciences, University of Newcastle

McLean Hospital’s famous patients included Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell, as well as John Forbes Nash and Susanna Kaysen.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

By naming 'Pennhurst', Stranger Things uses disability trauma for entertainment. Dark tourism and asylum tours do too

Psychiatry and romantic love

Revisiting Girl, Interrupted, I am struck by its raw and honest recognition of the way women have sometimes experienced relationships with men as inherently oppressive. The structures of psychiatry and romantic love intersect throughout this book.

Kaysen, like Plath, sees the family as a toxic institution. Male psychiatrists loom over both women, imposing in their authority to diagnose. “He looked triumphant”, wrote Kaysen of her doctor. “Doctor Gordon cradled his pencil like a slim, silver bullet”, wrote Plath.

Women writing about their own madness has a long history. American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) penned the story The Yellow Wallpaper in The New England Magazine in 1892. It tells the tale of a woman’s mental and physical exhaustion following childbirth.

Historians such as Elizabeth Lunbeck write about the way a “psychiatric persuasion” came to dominate thinking about gender in the early 20th century. Psychiatrists began to see everyday life difficulties – such as the changes experienced during adolescence – as signalling illness (we might say, pathologising “normal” responses to stressful events). The rise of psychiatric expertise paralleled their professional reactions to women (and men) who struggled with life.

In Australia, the history of “good and mad women” up to the 1970s by Jill Julius Matthews showed that women who experienced hospitalisation as a result of mental breakdown were perceived as having “failed” to meet the gendered expectations of them. Femininity and its constraints left some women unable to function or live authentic lives.

Institutions on film

Girl, Interrupted was released as a film by Columbia Pictures in 1999, with a cast of rising and established young actors, including Winona Ryder, Angelina Jolie and Brittany Murphy. It dramatised the interpersonal relationships inside the hospital described by Kaysen.

The film script was not only the perfect vehicle for an ensemble cast of these women. It was also another opportunity to make mental illness visible on the screen. Another page-to-screen adaptation in 1975, Milos Forman’s film of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, brought to life the dramatic environment of institutional control and violence personified by the character of Nurse Ratched.

Girl, Interrupted, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, emphasised resistance to institutional control.Girl, Interrupted’s screenplay surfaced different women’s experiences of abuse, neglect, trauma and violence to explain their behaviours and responses to institutional constraints.

Like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the film also emphasised the theme of resistance to institutional control. Patients hid pill medications under the tongue, broke into the hospital administration office to look at their case files, and found ways to circumvent the routines of institutional life. The film depicted the drama of group therapy, and the power dynamic between staff and patients.

Not everyone who was institutionalised reacted the same way to being in hospital.

Kaysen wrote:

For many of us, the hospital was as much a refuge as it was a prison. Though we were cut off from the world and all the trouble we enjoyed stirring up out there, we were also cut off from the demands and expectations that had driven us crazy.

A recent collaborative history of institutional care by Australian poet Sandy Jeffs and social worker Margaret Leggatt, Out of the Madhouse, challenges the idea of the institution as a place of alienation. Jeffs found community and solace at Larundel Hospital in Melbourne in the late 1970s and 1980s. However, the book also acknowledges this is not a universal response for institutionalised people.

Like Kaysen, people with lived experiences of mental illness and hospitalisation have found it therapeutic to write about their personal challenges. For some, it provides an opportunity to embrace the “mad” identity, to find empathy for others. And to create a new self out of the chaos of mental breakdown.

Authors: Catharine Coleborne, Professor of History, School Humanities, Creative Industries and Social Sciences, University of NewcastleRead more