MUP has commissioned a centenary history. The result is illuminating, but in striving for 'neutrality' it falls short

- Written by Dominic Kelly, Adjunct Research Fellow, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy, La Trobe University

Privately commissioned histories sit oddly within the Australian book market. Often produced as acts of institutional vanity or exercises in public relations, many are no doubt read only by members of the institutions themselves, and ignored by the wider reading public.

Review: MUP: A Centenary History – Stuart Kells (The Miegunyah Press)

But for the three principal partners in their development – author, institution, publisher – they can be attractive prospects.

The author gets to do what they do best – research and write – and is usually paid well for their efforts. The institution gets a competently written, well-produced volume to distribute to members, clients, supporters, whomever – its shiny, glorious history enshrined in print forever. And the publisher assumes little risk, providing its publishing resources and know-how while leaving the commissioning institution to shoulder the financial burden.

However, as Paul Ashton and Chris Keating note in The Oxford Companion to Australian History, there are dilemmas involved for historians accepting such commissions, “especially the need both to satisfy a client and to maintain professional independence.” They nevertheless conclude that “many historians continue to produce commissioned histories of the highest standards.”

One of Australia’s most prolific and successful historians, Geoffrey Blainey, launched his career in the 1950s with commissioned histories of the University of Melbourne and the National Bank of Australasia, among several others. Blainey “did not have the remotest desire to be an academic – he wanted to be a writer of history who could make a living from his writing.” He did settle into a more conventional academic career in the 1960s, however.

Stuart Kells, an adjunct professor at the La Trobe University Business School and author of several well-received books on publishing and libraries, appears to be inverting Blainey’s trajectory – turning away from conventional academia in favour of privately funded work as a freelance historian.

In the past few years, Kells has published two commissioned histories: on St Michael’s Grammar School and a commercial law firm. Now he has produced another: a centenary history of Melbourne University Press.

This project is distinct from Kells’s previous work, in that the commissioning institution and publisher are one and the same entity. This may have made things simpler with regard to managing relationships and expectations, but more complicated in terms of maintaining authorial independence.

Though the book doesn’t quite resolve the latter issue, especially when it comes to MUP’s recent history, Kells, a passionate bibliophile with extensive experience in institutional archival research, has done a fine job.

Read more: Friday essay: the library – humanist ideal, social glue and now, tourism hotspot

Modest, unglamorous early years

Though MUP set out to emulate the great university presses of Oxford and Cambridge, its output was modest in its first decade of operations. The word “press” in its name implied book production, but initially, MUP operated as a bookseller, a stationery store, a gown-hiring service, a post office and a telegraph department.

Of these unglamorous functions, “the book-room was far and away the chief activity of the press” in the 1920s, but MUP did begin to publish books in partnership with Macmillan, the British trade publishing giant. MUP’s ambition to become a publisher aligned with the 1918 declaration of the president of Columbia University:

A university has three functions to perform: It is to conserve knowledge; to advance knowledge; and to disseminate knowledge. It falls short of the full realisation of its aim unless, having provided for the conservation and advancement of knowledge, it makes provision for its dissemination as well.

MUP published 56 titles in its first decade, but financial irregularities led to the removal of its physically and mentally unwell director, Stanley Addison, in 1931. The advertisement for his replacement was explicit: “Men Only”.

Read more: Reading the landscape: university publishing houses and the national creative estate

Deplorable sexism

In maintaining such appallingly sexist standards of the time, MUP was overlooking an outstanding internal candidate. Barbara Ramsden, who had begun working at the press in June 1931, was not invited to apply, in what Kells describes as “an indefensible mistake and part of a deplorable pattern”.

Socialist poet Frank Wilmot was appointed instead, and shifted the direction of the press in two ways. At a time of intensifying nationalist sentiment in arts and culture, he championed Australian writing; he was also a more prudent financial manager.

But as Kells demonstrates, “Wilmot’s MUP was also Ramsden’s MUP.” Ramsden would become “the backbone of the press.” When Wilmot died suddenly in February 1942, she was effectively left in charge, but paid substantially less than Wilmot had been. When the permanent role was finally advertised in March 1943, Ramsden applied, and was unsuccessful. She found her new boss, Gwyn James, “erratic and irascible”. Yet she stayed on throughout his tenure and beyond, finally retiring from the press in 1967.

Kells quotes Peter Ryan, who took over from James in 1962, to capture the remarkable extent of Ramsden’s role and influence:

The wide span of her duties encompassed staff management, administration, supporting the board, managing suppliers, and “all the important and delicate decisions that attend editing, design, typesetting, proofreading, printing and distribution of works of high scholarship.”

Without question, Ramsden is the unsung heroine of the history of MUP.

Peter Ryan’s partial mea culpa

Ryan was an ambitious and rigorous director of MUP, who brought stability and financial security to the press. An eccentric man who enforced high standards, he was also unafraid of controversy. His immodest publishing philosophy was “to publish across the whole world of scholarship, but to publish nothing but the best.”

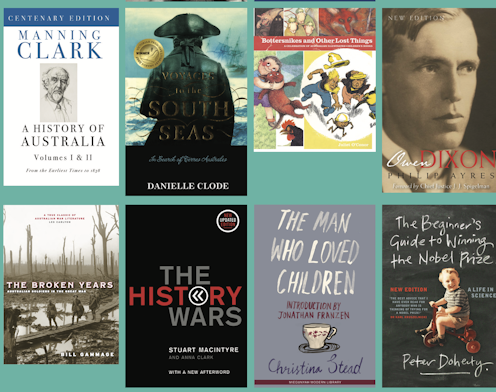

Ryan inherited and, to his regret, honoured Gwyn James’s open-ended commitment to publish as many volumes of Manning Clark’s A History of Australia as he chose to write. The six eventual volumes were all published during Ryan’s 26-year tenure. As their quality declined with each volume, they increasingly became the bane of Ryan’s professional life.

This all become public knowledge when Ryan recounted his experiences with Clark in Quadrant magazine in September 1993. Ryan delivered a full-throated attack upon Clark, who had died in 1991. Castigating the historian for his sloppiness with facts, Ryan described publishing the series as the greatest shame of his life. Clark’s History, he wrote, “remains largely an imposition on Australian credulity – more plainly, a fraud.”

Ryan’s essay caused a considerable furore. In quoting many of the participants, Kells presents a balanced view of the affair. However, his failure to cite Doug Munro’s History Wars: The Peter Ryan–Manning Clark Controversy (2021), despite recommending it for further reading in his acknowledgements, is significant.

Critically, Kells leaves out Munro’s documented proof that Ryan repeatedly misrepresented the contractual relationship between Clark and MUP. Far from being tied to an open-ended commitment, which was never formalised, Ryan negotiated and signed an agreement for four volumes in 1963, and agreed to variations thereafter. He also failed to make any provision for peer review, which goes some way to explaining why so many of Clark’s errors survived the editing process. Perhaps Ryan’s acrimony was as much a reflection on his own failings as Clark’s.

The Adler era and beyond

The 1990s were a period of instability for MUP. The appointment of hardline neoliberal Alan Gilbert as vice-chancellor of the university, along with shaky finances and several changes in leadership at the press, did not bode well for its future. A review of its operations led to the 2003 appointment of Louise Adler as chief executive officer. It had taken 80 years to appoint a female leader.

With a CV that includes stints at The Age, the ABC, the Victorian College of the Arts and Australian Book Review, Adler is as Melbourne arts establishment as they come. Controversy seems to follow her everywhere. Most recently, as director of Adelaide Writers’ Week, she has maintained a refreshingly principled stand on free expression for Palestinian writers in the face of a barrage of criticism.

Read more: Free speech or 'genocide cheering'? Ukranian authors withdraw from Adelaide Writers' Week

As CEO of MUP, Adler was tasked with commercialising the press. That is, improving the bottom line by commissioning more profitable titles for a general readership. Although MUP had always published non-academic books, this had been done so on the understanding that they were assessed as rigorously as scholarly publications.

Under Adler, these standards slipped dramatically, while the advances paid to popular authors skyrocketed. Eyebrows were raised at the parade of self-serving political memoirs, some far less worthwhile than others. She also commissioned the publication of books that simply had no place on the list of an academic publisher – most notoriously, the autobiography of Melbourne underworld figure Mick Gatto.

The whispered complaints of scholars gradually grew into a cacophony, finally leading to a university-imposed shift in direction in 2019, after which Adler and five other board members resigned. I have written elsewhere about this controversy, so I won’t repeat myself here; suffice to say that the change in direction was the cause of much relief for those who value the reputation of an academic press.

Intriguingly, Kells did not seek comment from Adler about the 2019 imbroglio. According to a recent profile in The Age, Adler is “annoyed and disappointed” about this. She has a point. Adler is one of the few people associated with the affair who declined to comment as it unfolded. Some reflection from such a key player, four years after the fact, would have been useful.

Kells instead chose to rely on evidence in archives and public commentary, which he says allowed him to maintain his neutrality. But there is no reason why an interview with Adler would have challenged this neutrality. On the contrary, his decision to not give her a right of reply brings into question his authorial independence – was there an instruction from the university or the press not to include Adler’s voice in MUP’s official “neutral” version of what happened?

Furthermore, Kells’s section on Adler’s replacement, Nathan Hollier, lacks objectivity. Hollier is his subject as well as his commissioning editor, and Kells heaps praise on what Hollier is doing with the press. I raise this not to disagree with Kells – for what my outsider’s perspective is worth, I think Hollier is doing an excellent job of restoring MUP’s reputation – but to question whether he is truly in a position to make an objective assessment of his own publisher.

All of which is to say, commissioned histories will continue to be problematic as long as they continue to be published. For all of my qualms about some of Kells’s authorial judgements, this is a worthwhile and illuminating book, and an important contribution to Australia’s literary and intellectual history.

CORRECTION: This article originally stated that Stuart Kells has previously written four commissioned histories. Two of those were not in fact commissioned.

Authors: Dominic Kelly, Adjunct Research Fellow, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy, La Trobe University