The most life-changing books can seem like they have always been there. What they say may seem obvious, once we’ve read them. But that’s only because they’ve reshaped how we look at things.

The French philosopher Pierre Hadot (1922-2010) began his intellectual career as a trainee priest and philologist (a student of ancient books), with an interest in forms of mysticism. Yet through his philosophical studies and writing, he has become globally renowned, exerting a huge influence in the realm of modern Stoicism.

Hadot’s best known work is his 1995 book Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault, based on a 1981 French collection.

I came upon it indirectly in 2008, through a university friend’s class on authors who had influenced the renowned philosopher, Michel Foucault. I was almost immediately captivated.

Hadot tells us in this book that his goal is to make people “love a few old truths”. In my case, and for many thousands of others around the world, he succeeded profoundly.

Read more:

Explainer: the ideas of Foucault

Ways of life

Philosophy as a Way of Life argues that the way we mostly think about philosophy today, as the professional pursuit of a tiny number of experts, is only a comparatively recent thing.

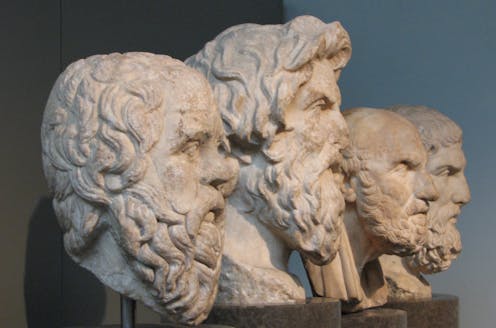

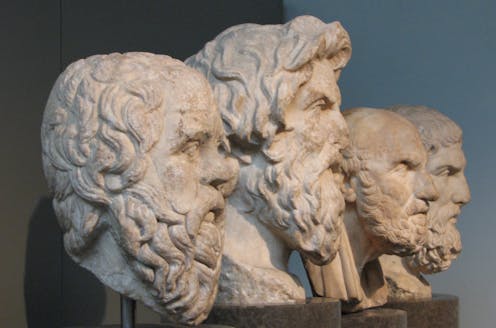

To be a philosopher in the ancient world, Hadot contends, involved much more than learning expert techniques of reasoning, analysis, and writing. Ancient philosophers adopted the “way of life” of one or other of the philosophical schools, whether Platonist, Aristotelian, Stoic, Epicurean, or the Cynics’. Philosophers of the ancient world, Hadot writes, became a kind of recognised, somewhat “edgy” cultural group. Comedies were even written about them.

For their part, Hadot stresses, the philosophers tended to see people in everyday life as caught up in needless fears and empty desires. As he writes, without examining our opinions, and those of our societies, we live out a kind of “inauthentic condition of life, darkened by unconsciousness and harassed by worry”.

Philosophies like Stoicism did not only challenge how students thought, but prompted them to “relearn how to see the world”, as Hadot writes, (echoing the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty). They could try to become less harried and wiser human beings.

Philosophies of living

Hadot does not deny that ancient philosophers developed highly complex theoretical visions of nature and human nature. He spent decades studying the metaphysical systems of later antiquity. But, he shows that ancient philosophers also sought to draw ethical and existential consequences from these theoretical understandings. They believed that, as reflective beings, what we think can and should change how we live.

Pierre Hadot in 1997.

Wikimedia Commons

So, take Epicureanism. If everything in the universe (as the Epicureans claimed) was made of material atoms, Hadot stresses, this mattered practically. It meant there could be no interventionist deities for people to fear. Death would also be “nothing to us”. For it will only be the dispersion of the atoms making up our souls, which we won’t be around any more to experience.

Of course, Hadot thinks scholars should still analyse the theoretical and technical components of ancient texts. Philosophy as a Way of Life, however, issues an unmistakable challenge to readers to apply the ancient philosophical ideas to improve our own everyday lives.

As Hadot explains his method:

If one says directly, do this or that, one dictates a conduct with a tone of false certainty. But thanks to the description of spiritual exercises lived by another, one allows a call to be heard that the reader has the freedom to accept or refuse. It is up to the reader to decide…

Spiritual exercises

Hadot stresses that the ancient philosophers realised it’s hard for people to challenge old beliefs, conquer negative emotions, and live consistently in light of their deepest, reasoned beliefs, given the many obstacles and distractions of life. He thus introduces arguably his most important, yet controversial idea in this book: that of these “spiritual exercises”.

Many ancient philosophical texts, Hadot argues, can only be rightly understood as involving philosophers’ recommending and practising specific meditative, cognitive and imaginative exercises whose goal was to transform not just how they thought, but what they felt and did on a daily basis.

In Stoicism, for example, students are enjoined to premeditate the worst that can happen, and prepare themselves in advance for adversities; taught techniques to assess situations whilst bracketing their subjective, passionate judgments about things and people; or again, asked to imagine their troubles as if they were looking down from a height, so they can appreciate how small we each (and our problems) are on the cosmic scale.

Philosophies such as Epicureanism and Stoicism, he writes, can thus “nourish the spiritual life of men and women of our times”, despite the long centuries since they were penned.

These claims mightn’t sound radical. But Hadot’s idea that philosophy could do anything “spiritual”, as against intellectual – let alone nourish the lives of modern men and women – has led to a great deal of criticism. Hadot has been charged with making philosophy into “religion” or of underplaying the place of reasoning and analysis in the discipline.

After well over a decade of academic study of philosophy, Hadot’s argument was a revelation to me. His point was that books like Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations don’t make sense unless we acknowledge that in them, we are witnessing a philosopher working his theoretical ideas (in this case, Stoicism) into a daily regimen, to deal with the nuts and bolts of his life: from people behaving badly to his own desires and fears.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: how Marcus Aurelius' Meditations can help us in a time of pandemic

Rather than endlessly chasing theoretical originality, philosophy – in this ancient model – is about challenging ourselves to live more fully, more rationally, more humanely.

The “fascinating power” of Meditations, for instance, lies precisely for Hadot in how, when we read this text, “we have the feeling of witnessing the practice of spiritual exercises – captured live …” We are witnessing, he argues, “someone in the process of training himself to be a human being.”

This depiction of philosophy as speaking to everyday and yet fundamental concerns resonated for me. Indeed Philosophy as a Way of Life led me to read the ancient Stoics, led by Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, as sources of exercises and guidance in everyday life, as well as objects of professional research. My wife and I even called our boy, Marcus.

Some time later, I became involved in the global modern Stoicism community, contributing to events, blogs, and magazines. In the COVID years, I became one member of the organising team of the Melbourne Stoicon-X event, which brings Australians interested in Stoicism as a way of life together each October to discuss these ancient ideas and share experiences.

None of this would have happened, if I hadn’t happened upon Hadot’s book.

To bring old ideas to life

Reading Philosophy as a Way of Life is like being given the keys to a series of wonderful conversations about how best to live that have been widely forgotten, but flourished (in the West) from Plato, at least, to Michel de Montaigne.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Michel de Montaigne's Essays

By asking us to reconsider texts by the Epicurean, Stoic, Platonist, Christian and Renaissance philosophers, Hadot’s wonderful book opens up a treasure trove of practical exercises, which speak directly to the adversities fortune throws at us.

Perhaps not everyone needs a book like this, and that is to be admired. But a great many in our unsettled world might benefit, as I have done, from keeping a copy of Philosophy as a Way of Life on their shelves, learning from it to love a few old truths.

Stoicon-x Melbourne is on Saturday 29 October, as part of global Stoic week. Speakers will include diver, cave explorer and former Australian of the Year Craig Challen.

Authors: Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

Pierre Hadot in 1997.

Wikimedia Commons

So, take Epicureanism. If everything in the universe (as the Epicureans claimed) was made of material atoms, Hadot stresses, this mattered practically. It meant there could be no interventionist deities for people to fear. Death would also be “nothing to us”. For it will only be the dispersion of the atoms making up our souls, which we won’t be around any more to experience.

Of course, Hadot thinks scholars should still analyse the theoretical and technical components of ancient texts. Philosophy as a Way of Life, however, issues an unmistakable challenge to readers to apply the ancient philosophical ideas to improve our own everyday lives.

As Hadot explains his method:

If one says directly, do this or that, one dictates a conduct with a tone of false certainty. But thanks to the description of spiritual exercises lived by another, one allows a call to be heard that the reader has the freedom to accept or refuse. It is up to the reader to decide…

Spiritual exercises

Hadot stresses that the ancient philosophers realised it’s hard for people to challenge old beliefs, conquer negative emotions, and live consistently in light of their deepest, reasoned beliefs, given the many obstacles and distractions of life. He thus introduces arguably his most important, yet controversial idea in this book: that of these “spiritual exercises”.

Many ancient philosophical texts, Hadot argues, can only be rightly understood as involving philosophers’ recommending and practising specific meditative, cognitive and imaginative exercises whose goal was to transform not just how they thought, but what they felt and did on a daily basis.

In Stoicism, for example, students are enjoined to premeditate the worst that can happen, and prepare themselves in advance for adversities; taught techniques to assess situations whilst bracketing their subjective, passionate judgments about things and people; or again, asked to imagine their troubles as if they were looking down from a height, so they can appreciate how small we each (and our problems) are on the cosmic scale.

Philosophies such as Epicureanism and Stoicism, he writes, can thus “nourish the spiritual life of men and women of our times”, despite the long centuries since they were penned.

These claims mightn’t sound radical. But Hadot’s idea that philosophy could do anything “spiritual”, as against intellectual – let alone nourish the lives of modern men and women – has led to a great deal of criticism. Hadot has been charged with making philosophy into “religion” or of underplaying the place of reasoning and analysis in the discipline.

After well over a decade of academic study of philosophy, Hadot’s argument was a revelation to me. His point was that books like Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations don’t make sense unless we acknowledge that in them, we are witnessing a philosopher working his theoretical ideas (in this case, Stoicism) into a daily regimen, to deal with the nuts and bolts of his life: from people behaving badly to his own desires and fears.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: how Marcus Aurelius' Meditations can help us in a time of pandemic

Rather than endlessly chasing theoretical originality, philosophy – in this ancient model – is about challenging ourselves to live more fully, more rationally, more humanely.

The “fascinating power” of Meditations, for instance, lies precisely for Hadot in how, when we read this text, “we have the feeling of witnessing the practice of spiritual exercises – captured live …” We are witnessing, he argues, “someone in the process of training himself to be a human being.”

This depiction of philosophy as speaking to everyday and yet fundamental concerns resonated for me. Indeed Philosophy as a Way of Life led me to read the ancient Stoics, led by Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, as sources of exercises and guidance in everyday life, as well as objects of professional research. My wife and I even called our boy, Marcus.

Some time later, I became involved in the global modern Stoicism community, contributing to events, blogs, and magazines. In the COVID years, I became one member of the organising team of the Melbourne Stoicon-X event, which brings Australians interested in Stoicism as a way of life together each October to discuss these ancient ideas and share experiences.

None of this would have happened, if I hadn’t happened upon Hadot’s book.

To bring old ideas to life

Reading Philosophy as a Way of Life is like being given the keys to a series of wonderful conversations about how best to live that have been widely forgotten, but flourished (in the West) from Plato, at least, to Michel de Montaigne.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Michel de Montaigne's Essays

By asking us to reconsider texts by the Epicurean, Stoic, Platonist, Christian and Renaissance philosophers, Hadot’s wonderful book opens up a treasure trove of practical exercises, which speak directly to the adversities fortune throws at us.

Perhaps not everyone needs a book like this, and that is to be admired. But a great many in our unsettled world might benefit, as I have done, from keeping a copy of Philosophy as a Way of Life on their shelves, learning from it to love a few old truths.

Stoicon-x Melbourne is on Saturday 29 October, as part of global Stoic week. Speakers will include diver, cave explorer and former Australian of the Year Craig Challen.

Authors: Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin UniversityRead more