Australia wasn't always supportive of India becoming independent. But 75 years on, relations have thawed

- Written by Amitabh Mattoo, Honorary Professor of International Relations, The University of Melbourne

On this day 75 years ago, after a long battle for self-government, Great Britain finally withdrew from the subcontinent – allowing independence for India and Pakistan.

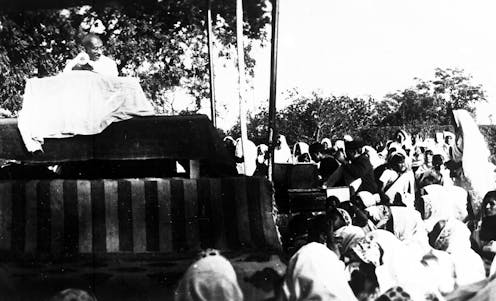

Once described as the “jewel in the crown”, the British withdrawal from the Indian empire was a reflection of the strength of the freedom movement, led by Mohandas Gandhi and others, as well as Great Britain’s plummeted standing as a power after the second world war.

As two countries part of the British empire, India and Australia had at least that in common. So what did India’s independence mean for its relationship with Australia?

A history of mistrust and neglect

There are few countries in Asia today that have more in common in both values and interests than India and Australia. The recently signed Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (EKTA) and the deepening security cooperation through the “Quad” (the Quadrilateral security dialogue, which also includes Japan and the United States) are examples of the robustness of the bilateral relationship.

But this was not always the case. For nearly six decades, bilateral relations were characterised by misperception, lack of trust, neglect, missed opportunities and even hostility.

Historically, Australia and India established diplomatic relations even before India’s independence. New Delhi set up a High Commission in Canberra in 1945, while Australia had done so a year earlier.

In April 1947, Australia sent observers to the Asian Relations Conference in Delhi hosted by India’s future prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, signalling its willingness to identify with the “National Movements for Freedom” of the colonised countries of Asia. The then Labour government of Prime Minister Ben Chifley welcomed India’s independence and its willingness to be part of the Commonwealth.

However, this diplomatic honeymoon dramatically changed after Robert Menzies became prime minister in 1949. Menzies had been sceptical about India’s independence, describing it as a country that had “not yet reached the stage at which the majority of its people are by education, outlook and training, fit for self-government,” and disagreed with India’s decision to become a republic although remaining part of the Commonwealth of States.

In 1955, Menzies – Australia’s longest serving prime minister - went further. He decided Australia should not take part in the Bandung Afro-Asian conference. By distancing Australia from the “new world”, Menzies (who would later confess that the western world did not understand India) alienated Indians, offended Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s longest standing prime minister) and left Australia unsure, for decades, about its Asian identity.

Through these years, India and Australia rarely had a meaningful conversation. The reasons are not difficult to identify: the White Australia Policy, the Cold War, the Nehru-Menzies discord, India’s economic policies which strived for self-sufficiency, Canberra’s strident response to New Delhi’s nuclear tests in 1998, and attacks on Indian students in Victoria in 2009.

The legacy of each was long-lasting: years after the White Australia Policy became history and Australia became one of the most multicultural nations, it seemed, at least anecdotally, that most Indians were unaware of this fundamental change. The only exposure most Indians had to Australia was to the Australian cricket team — the least multicultural of institutions. We used to celebrate each other’s problems rather than our successes.

Improved relations

A new chapter in India’s relations with Australia began in the second decade of the 21st century. In September 2014, the visit of Liberal prime minister, Tony Abbott, to India — also the first stand-alone state visit to be hosted by the Narendra Modi-led government — brought any sour historical relations to a close.

Read more: Abbott’s visit to take Australia-India relations beyond cricket

In a reciprocal gesture, two months later Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit Australia in 33 years. The last Indian prime minster to visit Australia had been Indira Gandhi, a visit remembered for its insignificance since it did nothing to improve relations.

Today, apart from being two English-speaking, multicultural, federal democracies that believe in and respect the rule of law, both have a strategic interest in ensuring a balance in the Indo-Pacific and in ensuring the region is not dominated by any one hegemonic power. In addition, Indians are today the largest source of skilled migrants to Australia.

Relations between India and Australia have deepened dramatically over the past decade. India’s economic growth and its burgeoning demand for energy, resources and education have made it suddenly one of Australia’s largest export markets.

Beyond the trade links, there is the shared concern in Canberra and New Delhi about security and stability in the region. We are living through a period of immense turbulence, disruption and even subversion. The near overwhelming presence of an illiberal, totalitarian China, increasingly unilateralist, interventionist and mercantilist - willing to write its own rules – is the single biggest challenge to the two countries. It was for this reason the Quad partnership began.

Lessons for Australia

As India and Indians celebrate the 75th anniversary of independence, it is more than just an event. For Indians independence was the culmination of a struggle of nearly 200 years, and the decades after independence have demonstrated the country’s growth as a self-confident country.

It has sustained, for the most, itself as a liberal democracy and improved its standing in the international system while earning the respect of the rest of the world, despite continuing problems.

Perhaps it’s time Australia – learning from the Indian example - declared itself as a republic, became much more inclusive in terms of empowering the Indigenous people, and recognised that it is today an Asian country, in a real sense, rather than being part of the Anglosphere.

Authors: Amitabh Mattoo, Honorary Professor of International Relations, The University of Melbourne