With surgery waitlists in crisis and a workforce close to collapse, why haven’t we had more campaign promises about health?

- Written by Henry Cutler, Director, Centre for the Health Economy, Macquarie University

This election campaign has been somewhat different to most past campaigns. Traditionally, the Coalition campaigns on the economy and defence, while the Labor Party tenders its credentials on health and education.

However, this time around has seen a dearth of announcements across all portfolios, and from both parties.

Health care is no exception, despite COVID blowing out surgery wait times and a health-care workforce close to collapse.

Why are political parties and voters so apathetic to the health-care debate?

Health policy announcements so far

The Coalition promises to reduce out-of-pocket costs for medicines listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and will give more people access to the seniors’ health-care card. These policies are targeted at older Australians.

Labor has also promised to reduce out-of-pocket costs for pharmaceuticals and increase access to the seniors’ health-care card. It will introduce GP urgent care clinics and will support aged-care wage increases and mandating nurse time in residential care homes.

These are mostly promises to increase funding. No party has sought to engage in serious debate on reform, despite a long list of identified system issues and intense pressure points.

Why isn’t there more health-care debate?

It seems health care is just not as important to voters in this election.

On average, voters ranked it their sixth most important issue, which is three down from the last election, when it was ranked third.

That is not surprising when there are big issues at front of mind, such as climate change, cost of living increases, and rising interest rates.

Most people feel comfortable with the state of health care. A consumer sentiment survey found 84% of respondents were satisfied with the health services they received.

Parties are also hamstrung this election. Health care reform is expensive, and promising big spends when the budget is at a record deficit, opens the potential for being labelled fiscally irresponsible.

Labor seems to be low-balling its health policy given it leads the polls. It learned from the last election that proposing complex policy through campaign soundbites is risky, because it’s too easy to criticise step-change reform.

The Coalition launched its health campaign in the budget. It took a grassroots approach to wooing voters, with no big policy announcement but lots of smaller funding promises dispersed across electorates. Battling Labor on health in the election lead-up seems unattractive for the Coalition given its poor handling of vaccine purchasing and rollout.

But whoever wins, health care remains a problem that needs to be addressed.

Long surgery wait lists

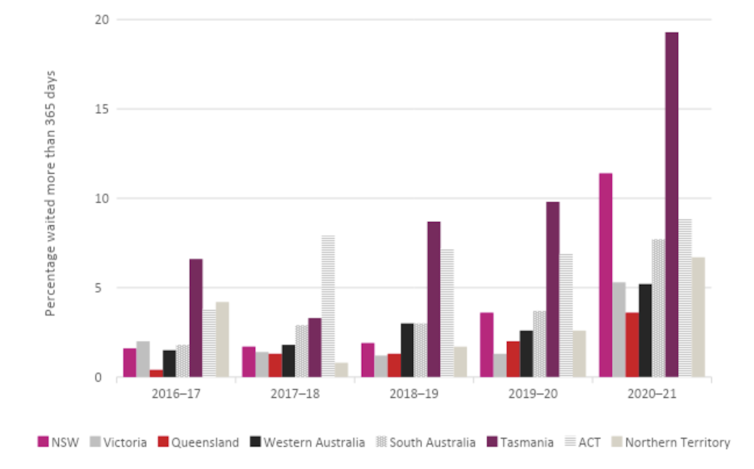

People are waiting longer than ever before for public hospital elective surgery, with COVID blowing out waiting lists in 2020-21.

A key reason is the initial suspension of non-urgent elective surgery to deal with COVID in 2020.

Victorian waiting times were hardest hit. They experienced a threefold increase in the number of people waiting more than a year for elective surgery in 2020-21. New South Wales was hit next hardest, experiencing a twofold increase.

Non-urgent elective surgery was also suspended during the Delta and Omicron waves. These will have blown waiting times out further, which is not yet reflected in the data. All states and territories are still playing catch-up.

Workforce collapse

Most of Australia’s health workforce seem weary, demotivated and burned out. Some 92% of 431 clinicians surveyed in January 2022 agreed health-care workers have a right to feel abandoned by government.

With unemployment at 4%, the labour market has little spare capacity to increase the supply of workers.

Health care and medical job advertisements are at an all-time high and there are not enough candidates to fill these roles. Workforce shortages are being experienced all over Australia, in rural and remote regions and major cities. Psychiatrists are particularly in short supply - a key concern when 24% of Australians reported in October 2021 they were experiencing serious psychological distress.

Sectors with significant workforce gaps are buckling under pressure, such as nursing, and in some places would collapse if a mutated COVID strain were to outmanoeuvre current vaccines.

Workforce shortages lead to poor care quality, worse health outcomes and sometimes avoidable death. Poor workforce planning and funding constraints by governments over the last decade are mostly to blame.

Read more: A burnt-out health workforce impacts patient care

The Coalition government has released several health workforce strategies, but has not seriously implemented or funded promised activities.

Solutions the parties could offer

As a matter of urgency, any new government should lead collaboration with state government, private sector, non-government agencies, and specialist medical colleges to reduce surgery wait times and reduce workforce strain.

It is not ideological to suggest the public hospital system should strengthen its integration with private hospitals. Even a public hospital system that returns to full capacity will not have enough resources to shorten waiting times.

Public hospitals need more targeted money to streamline processes and patient journeys, improve wait-list management and prioritise strategies, and reduce low-value care.

Read more: The coronavirus ban on elective surgeries might show us many people can avoid going under the knife

Proactively matching patients with hospital resources by giving patients explicit public hospital choice would reduce waiting times. Many patients will travel to a non-local hospital for a shorter wait.

More investment in hospital-in-the home programs would free up hospital beds. And increasing training places at hospitals and ramping up migration would attract more nursing and specialist time.

Voters have not yet had the opportunity to signal their support for major health-care policy reform in this election. The real work leading health-care reform will be up to whoever’s in government after May 21.

Authors: Henry Cutler, Director, Centre for the Health Economy, Macquarie University