white settlers co-opting terms used to oppress

- Written by Bronwyn Carlson, Professor, Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University

This article mentions ongoing colonial violence towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

This week, actress Sam Frost made headlines for the use of the word “segregation” in an Instagram video. Frost, who is white, spoke emotionally about how her choice to remain unvaccinated made her feel “less of a human” in Australian society.

The video, which Frost has now deleted, refers to New South Wales easing restrictions on travel and socialising. She complains that vaccinated people are allowed out of lockdown as of October 11, while unvaccinated people have to wait until December 1.

The post received significant critique on social media where some called it an expression of white privilege.

By invoking segregation to describe what she frames as prejudice against her vaccination status, Frost likened her experiences as a white settler with unimpeded access to free health care to the violent racial discrimination, incarceration and forced removal experienced by Indigenous and migrant communities in Australia.

Comments like Frost’s demonstrate ignorance towards the many structural inequalities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and other marginalised peoples in Australia.

Settlers co-opting language they’ve used to oppress

Frost’s comments are part of a trend of white public figures and officials co-opting language describing racial violence and colonial government policies for their own means.

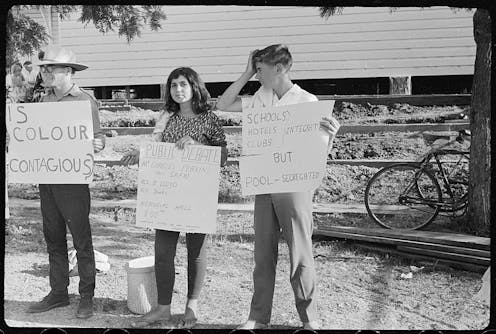

White settlers are co-opting terms like “medical apartheid” and “lynch mob”. These terms are used to describe inconveniences rather than the systemic injustices and violence they actually refer to.

In 2019, Donald Trump, then president of the United States, referred to his impeachment inquiry as “a lynching”.

Earlier this year, a deputy president at the Fair Work Commission, Lyndall Dean, likened vaccine mandates to “medical apartheid”.

Using terms like these is controversial not only because it appears to trivialise the mistreatment of marginalised people, but also because language communicates power. This is especially true in settler colonial nations like Australia and the United States. In these countries, white settlers use language to control, terrorise and marginalise Indigenous peoples, refugees and migrants.

Settler governments use language to create racial policies, including the forced removal and segregation of Aboriginal people. This entailed moving families off their homelands and onto missions and reserve lands where many people still live to this day.

So when terms like segregation are used, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are reminded what they really mean. Even if the person invoking it is only talking about having to stay inside.

The pandemic has highlighted privilege

White settlers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have not been impacted the same by the COVID-19 pandemic. White women like Frost feel free to deny free, potentially life-saving health care. Aboriginal women with COVID-19, meanwhile, are turned away from hospitals and fined for driving to get groceries.

Racial discrimination and segregation in Australia is not a thing of the past. Neither lockdown measures, nor the COVID vaccination rollout, have been equal or racially neutral.

Many have noted the differences of lockdown measures across suburbs. Western Sydney, which has one of the largest Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and migrant populations in Australia, was heavily policed during lockdown. Whereas, the affluent eastern and inner city suburbs had more relaxed restrictions.

The New South Wales government has not prioritised regional Aboriginal communities in COVID-19 plans. As a result, communities in Wilcannia, Dubbo and Bourke have been subject to deadly outbreaks, slower vaccination rates, and military presence.

As states and territories begin reopening, the levels of anxiety and dread are rising in these communities – especially in places where less than 35% of Aboriginal and Torres Islander people over the age of 12 are double vaccinated.

This is one reason why Aboriginal health services are racing to make sure people in our communities are getting vaccinated.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Isabel Flick, the tenacious campaigner who fought segregation in Australia

A history of medical apartheid

Any vaccine hesitancy in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is understandable considering the history of racialised medical violence in Australia. This includes medical experimentation in “lock hospitals”, where some people never returned from.

African-American medical ethicist Harriet A. Washington has researched similar instances of what she refers to as “medical apartheid” in the US. Washington writes of the way western medicine both neglects and relies on the abuse of Black and Indigenous peoples.

In Australia, Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations continue to respond to issues caused by racism in mainstream health services. We are only just beginning to see how much lockdown measures and barriers to accessing health care have harmed and endangered marginalised communities.

Much of what we know so far is thanks to diverse journalists covering events as they unfold at ABC, SBS and NITV. There has also been grassroots coverage from marginalised communities through media outlets such as IndigenousX and Transdemic.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are also battling vaccine and COVID misinformation. Commentary from Frost and other Instagram influencers is not only dangerous, but also spreads inaccurate narratives of white victimhood.

It is a privilege to reject life-saving health interventions while others experience structural barriers to appropriate medical care.

Authors: Bronwyn Carlson, Professor, Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University