Do you think most people are trustworthy and helpful? How we measured 'social cohesion' and why its recent dip matters

- Written by Nicholas Biddle, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

COVID-19 has upended so many aspects of our lives in Australia, it can be hard to remember what life was like before the pandemic. It’s also hard to remember what we feared would happen when the pandemic first struck.

Some of the predictions have come to pass — there was a massive economic shock, travel and mobility have been constrained, mental health has suffered as lockdowns have been extended, and government budget deficits are at levels that would have seemed inconceivable only two years ago.

Another early prediction was that the pandemic would lead to a fraying in social cohesion.

In data released recently we show there’s been an increase in many aspects of social cohesion over the course of the pandemic. But this may be slipping as lockdowns drag on.

Read more: 5 questions to ask yourself before you dob — advice for adults and kids, from an ethicist

What does social cohesion mean?

Before discussing results from the most recent survey, it is worth reflecting on what “social cohesion” actually means.

It can mean different things to different people but one useful definition from a recent research report is:

the degree of social connectedness and solidarity between different community groups within a society, as well as the level of trust and connectedness between individuals and across community groups.

In other words, it’s about how much we trust each other, how connected we feel to others and to what extent we feel solidarity and empathy with others.

Social cohesion can operate at the individual, household, or community level.

How did we measure social cohesion?

Since April 2020, the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods has been running a multi-wave longitudinal survey tracking the outcomes, attitudes, and behaviours of a representative sample of Australians during the pandemic period. We wanted to see how these factors have changed over time.

Incorporated into the ANUpoll series of surveys, the data also allows us to track outcomes at the individual level from prior to the COVID-19 period. The study was carefully designed to ensure we could be confident the responses were free of many of the biases that plague many studies where people opt-in to participate.

In February (pre-COVID), May and October 2020, respondents were asked three questions related to social cohesion. These were repeated in August 2021, our most recent wave of data collection. The questions were:

“Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”

“Do you think that most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would they try to be fair?”

“Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful or that they are mostly looking out for themselves?”

These questions are asked across a range of social surveys in Australia and internationally.

All three questions were answered on a scale of 0 to 10, and averaged out to give a perceived social cohesion score on a scale of 0 to 10.

Individual-level data for all four surveys are available through the Australian Data Archive for any researcher to analyse.

A significant and substantial boost early on — but a recent dip

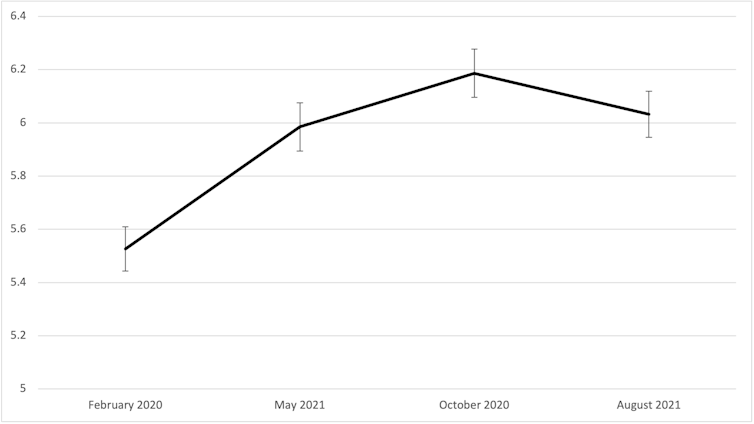

Our data suggests there was a significant and substantial improvement in social cohesion between February and May 2020 (the early stages of the pandemic). There was another increase between May and October 2020.

So rather than leading to an erosion of social cohesion, the pandemic — and arguably the government and societal response — appears to have enhanced it.

There was a slight but not statistically significant decline in perceived social cohesion between October 2020 and August 2021. However, perceived social cohesion is still significantly and substantially above what it was pre-COVID.

Perceived social cohesion in Australia, February 2020 to August 2021.

Perceived social cohesion in Australia, February 2020 to August 2021.

The greatest improvement over the COVID-19 period has been in the trust measure — from 5.40 (out of 10) in February 2020 to 6.02 in October.

The greatest decline over the last 10 months has been in whether people are perceived to be helpful. That declined from an average of 6.23 in October 2020 to 6.04 in August 2021, a difference that was statistically significant.

Why does it matter?

Measures of social cohesion are important in their own right. However, there are other reasons society should care about social cohesion.

One that has featured extensively in the literature is the reduction in the costs associated with buying and selling — what researchers and investors call transaction costs.

If people trust others to not harm them and to follow through on agreements, then there’s less need for expensive contracts and contract enforcement (think fewer court cases, expensive legal work, resource-intensive arbitration).

Causality is particularly difficult to show with this type of data but it’s possible social cohesion may also lead to or support pro-social behaviour — meaning positive behaviours like friendliness or helping one another.

Our data suggests there was a significant and substantial improvement in social cohesion in the early stages of the pandemic.

Shutterstock

Our data suggests there was a significant and substantial improvement in social cohesion in the early stages of the pandemic.

Shutterstock

Our data show, for example, that 38% of those who gave a value of 0 to 2 on the “helpful” question had been vaccinated as of August 2021, compared to 51% of those who gave a score of 3 to 6, and 66% of those who gave a score of 7 to 10.

In other words, those who perceive that people mostly try to be helpful are more likely to have been vaccinated.

Even though we have avoided the worst of the effects that some other countries have seen, COVID-19 has caused immense damage to Australia’s economic, social, and mental health.

One bright spot has been an increase in many aspects of social cohesion.

There are some initial indications that this may be dropping as lockdowns go on, and the end of the worst impacts does not appear to be in sight.

We should make sure that we do not lose our unexpected gains.

Read more: Victoria has announced extra funds for counselling, but it's unlikely to improve our mental health

Authors: Nicholas Biddle, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University