100 years of our most famous portrait prize and my almost 50 years watching it evolve

- Written by Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne

In 2008, when I first visited Canberra’s newly opened National Portrait Gallery, my first response was an overwhelming sense of déjà vu. I knew many of those paintings. They had once hung on the walls of the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of the annual Archibald Prize exhibition, or been seen in the Salon des Refusés — home to the best of the rejects.

Over 49 years I have seen the Archibald from both the inside, as a curator, and the outside as a critic. My first Archibald was in 1972, the year Clifton Pugh won with his portrait of Gough Whitlam. Along with other art history students, I had never been especially interested in this festival of popular culture, but as the recently appointed most junior of all curators my job was to administer the prize.

It is fair to say the gallery trustees who voted for the winning portrait (all appointed by Sir Robert Askin’s Liberal government) were not fans of the newly elected Labor Prime Minister. But Pugh’s painting dominated the longlist, the shortlist and the final exhibition, where I took great pleasure in hanging it so it was the first work people saw on arrival.

A finalist in 1969: John Brack, Barry Humphries in the character of Mrs Everage, 1969. Oil on canvas, 94.5 x 128.2 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased with funds provided by the Contemporary Art Purchase Grant from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council 1975 © Helen Brack

A finalist in 1969: John Brack, Barry Humphries in the character of Mrs Everage, 1969. Oil on canvas, 94.5 x 128.2 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased with funds provided by the Contemporary Art Purchase Grant from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council 1975 © Helen Brack

Since then I have seen almost every Archibald, and although some of my colleagues continue to loathe the annual feast of novelty portraiture, I have come to appreciate it as an annual snapshot of the kind of society we are, and who our heroes may be.

Proudly Australian

As the gallery celebrates the prize’s centenary and the ABC prepares to screen a documentary hosted by Rachel Griffiths, Finding the Archibald, which looks at the history of the prize and asks what the selected paintings say about us, it is worth remembering exactly why Archibald bequeathed some of his considerable estate to create an Australian portrait prize – and to give thanks for his vision.

The man born John Feltham Archibald in 1856, who later renamed himself Jules François Archibald because he loved France, was an Australian nationalist.

As founding editor of The Bulletin he fostered the literary careers of Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Miles Franklin and Steele Rudd – writers whose work defined the country as we moved towards Federation. His illustrators included Phil May, Will Dyson, D. H. Souter, George Lambert and Norman Lindsay. All projected a sense of an independent Australia.

At the beginning of last century, it was assumed an Australian’s success was made in England.

1939 finalist: Tempe Manning, Self-portrait 1939. Oil on canvas, 76 x 60.5 cm.

Private collection © Estate of Tempe Manning

1939 finalist: Tempe Manning, Self-portrait 1939. Oil on canvas, 76 x 60.5 cm.

Private collection © Estate of Tempe Manning

In 1900, when private philanthropy paid for Henry Lawson to travel north to London, the Melbourne artist John Longstaff painted his portrait, purchased by the Art Gallery of NSW the following year. Longstaff then also left for London.

Lawson soon returned home, but the absence of Longstaff and other talented Australians is one reason for the precise wording of Archibald’s will, enacted on his death in 1919.

He wanted our artists to see Australia as home, so he carefully wrote the prize would be for:

the best portrait of some man or woman distinguished in Art Letters Science or Politics painted by any artist resident in Australasia during the twelve months preceding the date fixed by the Trustees for sending in the Pictures …

Those words have been the subject of argument by generations of artists, critics and lawyers. When Longstaff first entered the prize in 1921 he was ruled ineligible as he had only just returned from England. In 1988, the same rule disqualified Sidney Nolan as he, too, was a UK resident.

A prize of the trustees

As the prize must be judged by the gallery’s trustees, it is possible to track the nature (and prejudices) of those trustees by looking at the artists awarded it, as well as their sitters.

The initial seriousness of the prize and its generous funding led to a bias towards the dull tonal work of W B McInnes who won a total of seven times.

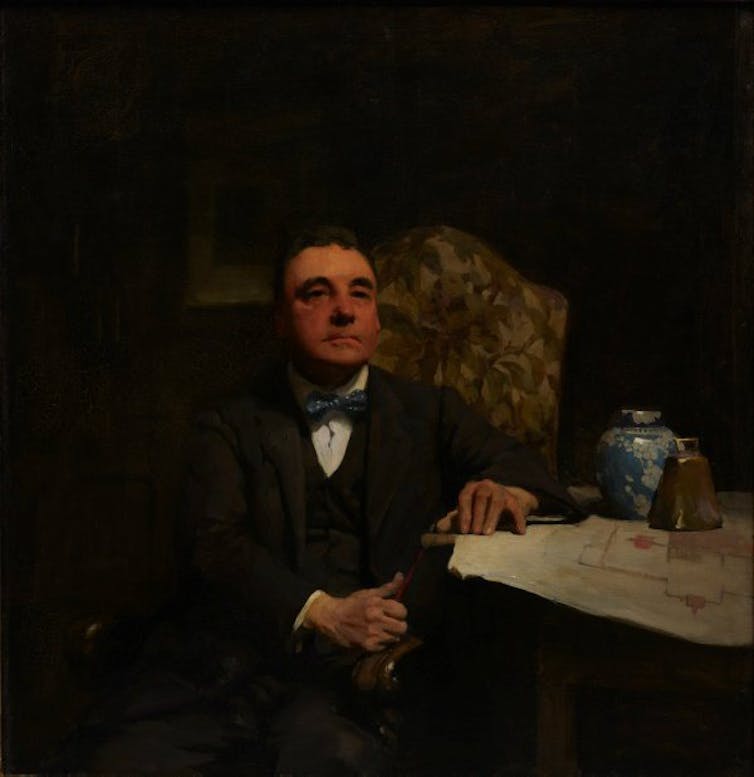

McInnes won seven times, first in 1921. WB McInnes, H Desbrowe Annear 1921. Oil on canvas, 107.5 x 104.2 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Gift of the artist 1922

McInnes won seven times, first in 1921. WB McInnes, H Desbrowe Annear 1921. Oil on canvas, 107.5 x 104.2 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Gift of the artist 1922

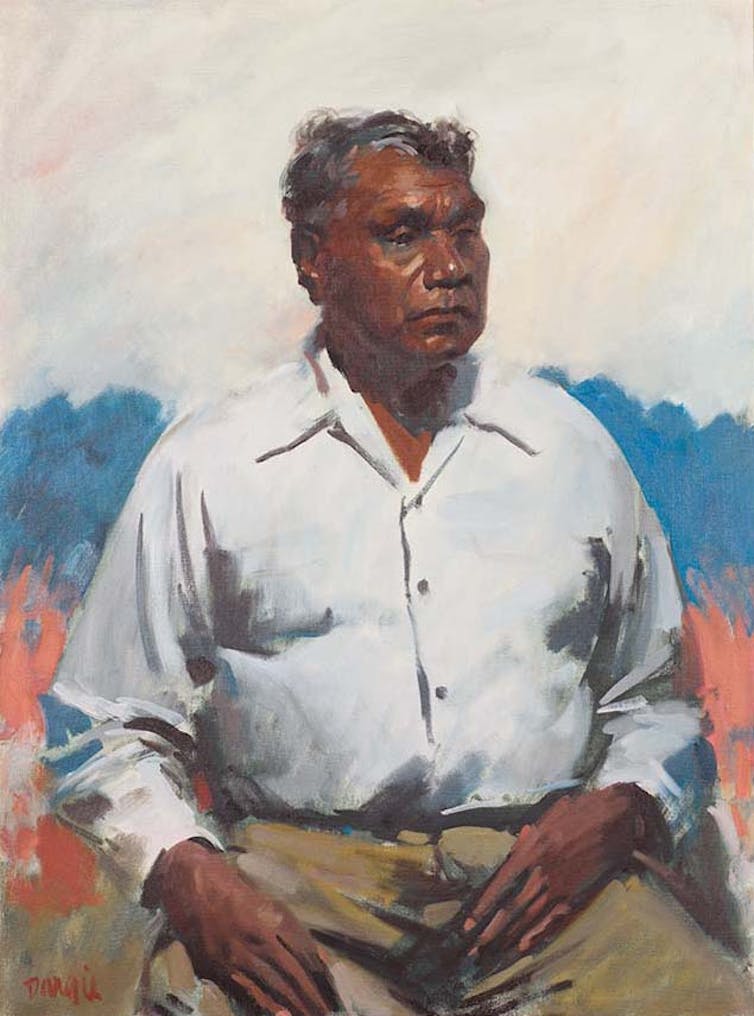

This record was beaten by Sir William Dargie with eight wins, the last one being in 1956 for his powerful portrait of Albert Namatjira, the first time a portrait of an Aboriginal person had won.

The first winning portrait of an Aboriginal person. William Dargie, Portrait of Albert Namatjira, 1956. Oil on canvas, 102.1 x 76.4 cm.

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Purchased 1957 © Estate of William Dargie Photo: QAGOMA

The first winning portrait of an Aboriginal person. William Dargie, Portrait of Albert Namatjira, 1956. Oil on canvas, 102.1 x 76.4 cm.

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Purchased 1957 © Estate of William Dargie Photo: QAGOMA

In 2020, Vincent Namatjira — Albert’s great-grandson — was the first Aboriginal artist to win the prize with Stand Strong For Who You are, a double portrait with Adam Goodes.

Winner: Archibald Prize 2020. Vincent Namatjira ‘Stand strong for who you are’. Acrylic on linen, 152 x 198 cm.

© the artist Photo: AGNSW, Mim Stirling

Winner: Archibald Prize 2020. Vincent Namatjira ‘Stand strong for who you are’. Acrylic on linen, 152 x 198 cm.

© the artist Photo: AGNSW, Mim Stirling

Archibald welcomed women writers throughout his journalistic career and made a conscious decision to include both genders in his will. Many women entered, but it was not until 1938 that Nora Heysen won with a portrait of Madame Elink Schuurman, wife of the Consul-General for the Netherlands.

The commentary that followed was especially distasteful as the artist, still the youngest ever winner at 27, had Schuurman wear a Chinese dress from her time living in Shanghai. In 100 years, the prize has only been awarded to women artists ten times. Six of those occasions have been in the last 20 years.

Winner: Archibald Prize 1938. Nora Heysen ‘Mme Elink Schuurman’ 1938. Oil on canvas.

© Lou Klepac

Winner: Archibald Prize 1938. Nora Heysen ‘Mme Elink Schuurman’ 1938. Oil on canvas.

© Lou Klepac

Sadly, this lively painting remains overseas and is unavailable for the centenary retrospective exhibition.

Read more: Friday essay: Nora Heysen, more than her father's daughter

Another absence is William Dobell’s 1943 portrait of Joshua Smith, effectively destroyed in a fire many years ago. As is the way of artists, Dobell and Smith had painted each other’s portraits. The year’s two finalists were Dobell’s portrait of Smith, and Smith’s portrait of the poet Dame Mary Gilmore.

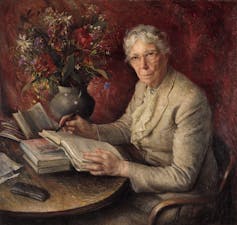

William Joshua Smith ‘Dame Mary Gilmore’ 1943. Oil on canvas, 85.7 x 92.3 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Dame Mary Gilmore 1945 © Yve Close Photo: AGNSW

William Joshua Smith ‘Dame Mary Gilmore’ 1943. Oil on canvas, 85.7 x 92.3 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Dame Mary Gilmore 1945 © Yve Close Photo: AGNSW

Lionel Lindsay, well-known as an anti-modernist, recognised the superior quality of the Dobell and so advocated for it, as did the only woman trustee, Mary Alice Evatt, recently appointed to the board by her brother-in-law, the Minister for Education.

After Dobell’s victory two unsuccessful artists, Mary Edwards (later known as Mary Edwell-Burke) and Joseph Wolinski, were persuaded by colleagues in the Royal Art Society to mount a court case to dispute the result, claiming Dobell’s work was not a portrait but a caricature.

They lost, but in the aftermath the Archibald became the most popular event for artists wishing to make their name.

Paintings of ideas

This year 938 works were entered and only 52 were hung. The inability to guarantee a sitter their portrait will be hung is one reason for the many self-portraits, portraits of fellow artists and family members.

These more intimate portraits have been among the most successful exhibits. For me, the most memorable of all is Janet Dawson’s 1973 portrait of her husband, the pioneering playwright, food writer, gardener, Michael Boddy.

I was in the packing room when it was being unwrapped. I still remember getting a shiver down my spine. Even under plastic it was so beautiful.

Winner: Archibald Prize 1973: Janet Dawson, Michael Boddy. Acrylic on bleached linen, 150 x 120 cm.

© Janet Dawson

Winner: Archibald Prize 1973: Janet Dawson, Michael Boddy. Acrylic on bleached linen, 150 x 120 cm.

© Janet Dawson

It is an especially lush and loving work. At the time Daniel Thomas, the gallery’s senior curator, wondered if women secretly wanted to eat their husbands.

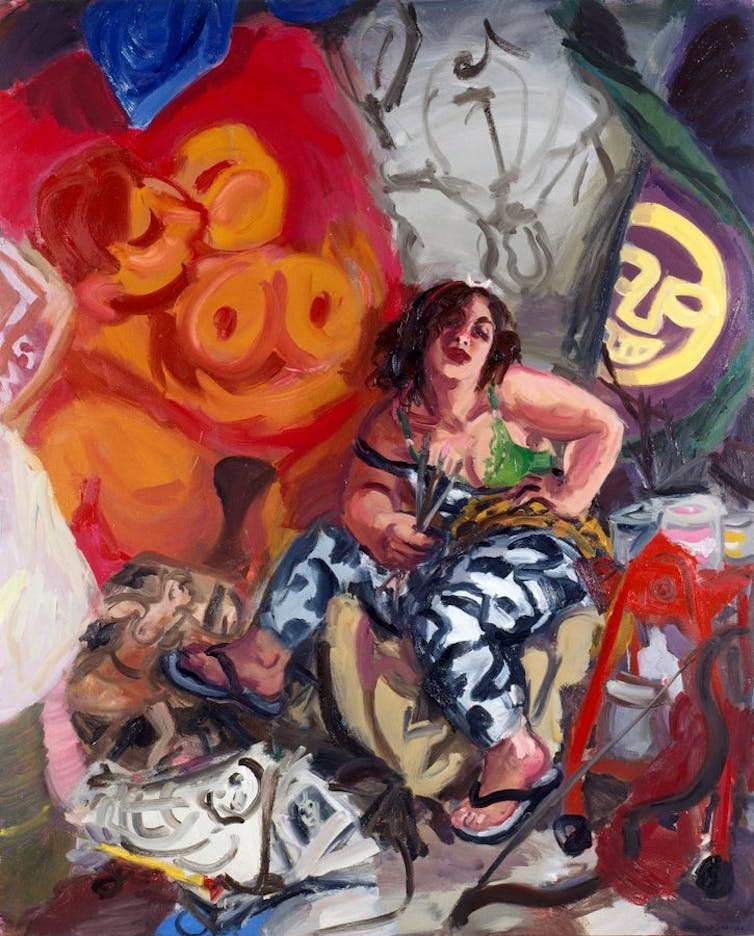

One truth about the Archibald rarely discussed is the influence of individual trustees. When Wendy Sharpe won in 1996 with her exuberant Self-portrait as Diana of Erskinville, there had just been a changing of the guard with the appointment of new trustees.

The announcement was delayed for almost an hour as the trustees deliberated. Word is, it was the advocacy of one of the newly appointed board members that gave her the prize by one vote.

Wendy Sharpe. Self-portrait as Diana of Erskineville, 1996. Oil on canvas, 210 x 172 cm.

Mr N and Mrs A Pezikian Collection, Sydney © Wendy Sharpe

Wendy Sharpe. Self-portrait as Diana of Erskineville, 1996. Oil on canvas, 210 x 172 cm.

Mr N and Mrs A Pezikian Collection, Sydney © Wendy Sharpe

It is true to say the trustees of 1920 would not share the aesthetic values of much of the art in recent exhibitions. Celebrations of cultural difference and gender and the presence of many works by Aboriginal artists would almost certainly be beyond their comprehension.

With the exception of the photo-realist works and the occasional academic portrait, realistic depictions of the subject are now the exception rather than the rule.

But what would Archibald think? He was, above all, a man of ideas. He wanted us to look to our own history in preference to that of England. He wanted Australians to debate our artists, writers, actors – even politicians.

I think he would be pleased.

Archie 100: A Century of the Archibald Prize is at the Art Gallery of NSW June 5 – September 26, then touring nationally.

Correction: a previous version of this story misstated the heritage of Elink Schuurman.

Authors: Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne