William Yang's work is a portrait of a life well lived

- Written by Chari Larsson, Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

Review: William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.

How does an image become an icon? Moreover, how does a photographer become iconic? A major survey exhibition of the work of Queensland-born, Sydney-based photographer William Yang goes a long way towards answering these questions.

Yang is a much loved photographer, performer and storyteller. This show at the Queensland Art Gallery is a celebration of Yang’s multifaceted practice that has steadily unfolded over the past five decades.

The act of seeing can be predatory and voyeuristic. In her classic 1973 book On Photography, Susan Sontag observed that the photographer’s camera “may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit”. The camera, however, can also be joyful and playful. Much of Yang’s work falls into the latter category. Operating in a highly intimate register, Yang’s ability to disarm his subjects is striking.

Organised roughly chronologically, the exhibition moves through the various phases of Yang’s life. Born in North Queensland in 1943, he is a third generation Chinese-Australian. Growing up in the town of Dimbulah, the experience of being an outsider features prominently throughout his body of work.

Yang’s family disavowed their Chinese heritage, preferring their children to assimilate. In his floor talk at the media preview, Yang described the experience of having to “come out” twice: first as a gay man, and second in search of his Chinese identity in his 30s.

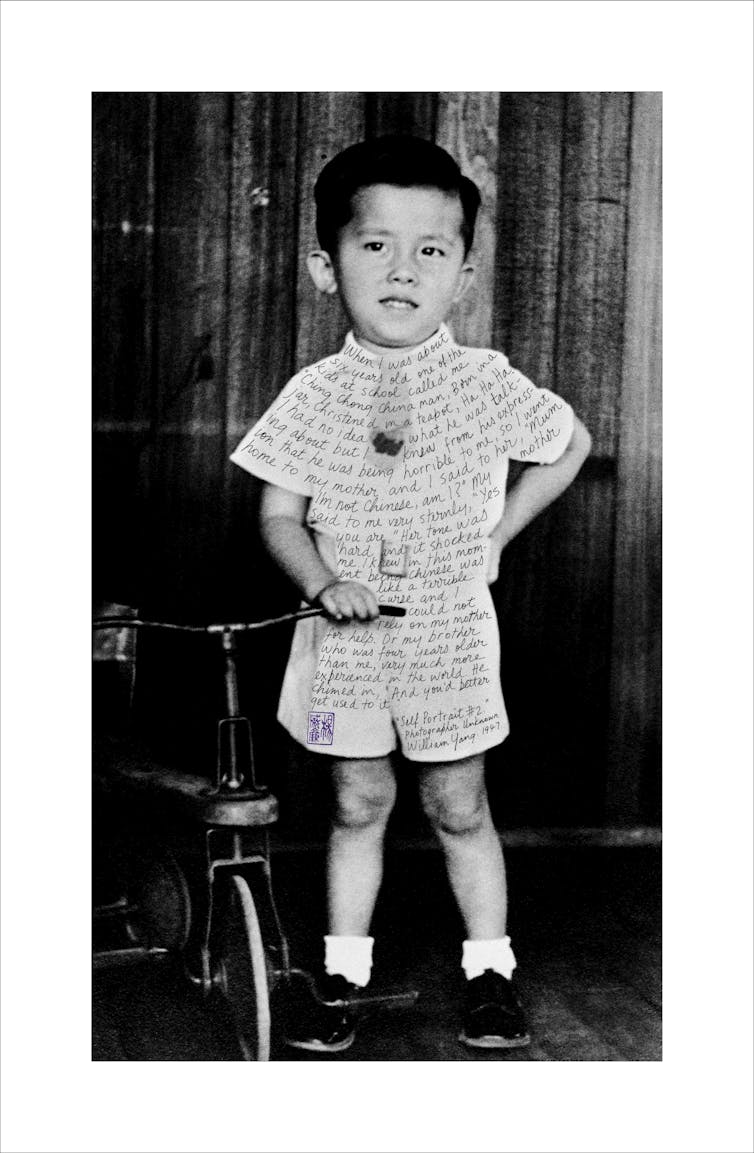

In one of his most iconic images, Life Lines #3 – Self-portrait #3, Yang rephotographs a vintage image of himself at age three and recounts in handwritten text the racist taunts he experienced at primary school.

William Yang.

Australia, 1943, Life Lines #3 - Self portrait #2 (1947) 1947/2008 photographer: Unknown. image 100.0 x 70.0 cm. Collection of The University of Queensland,

purchased 2010.

Photo: Carl Warner

Reproduced courtesy of the artist and

Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

William Yang.

Australia, 1943, Life Lines #3 - Self portrait #2 (1947) 1947/2008 photographer: Unknown. image 100.0 x 70.0 cm. Collection of The University of Queensland,

purchased 2010.

Photo: Carl Warner

Reproduced courtesy of the artist and

Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

This strategy features prominently throughout the exhibition. Yang will frequently rework his photographs, handwriting text onto the images. Through the repeated use of first person, Yang creates a sense of closeness with the viewer akin to sharing a diary or confession.

In his catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition, author and broadcaster Benjamin Law observes Yang possesses a “superpower”: an ability to create a sense of ease with his sitting subjects. Like a Möbius strip, Yang has traced his observations directly onto Law’s image, tracing the contours of his body and reinforcing the connection between photographer and subject.

William Yang, Australia, b. 1943, Ben Law. Arncliffe 2016, Inkjet print on Ilford Galerie Smooth Cotton Rag. Image courtesy the artist.

© William Yang

William Yang, Australia, b. 1943, Ben Law. Arncliffe 2016, Inkjet print on Ilford Galerie Smooth Cotton Rag. Image courtesy the artist.

© William Yang

Yang moved to Sydney via Brisbane in 1969, and found paid work as a social photographer. Working in a photojournalist tradition, which reaches back to New York-based photographers such as Nan Goldin and Diane Arbus, there was a complex duality at play.

On the one hand there is a warm exuberance characterising much of his social photography.

On the other, there is an urgent political undercurrent. What emerges is an important photographic archive of Australia’s emerging gay and lesbian communities in the 1970s and 1980s.

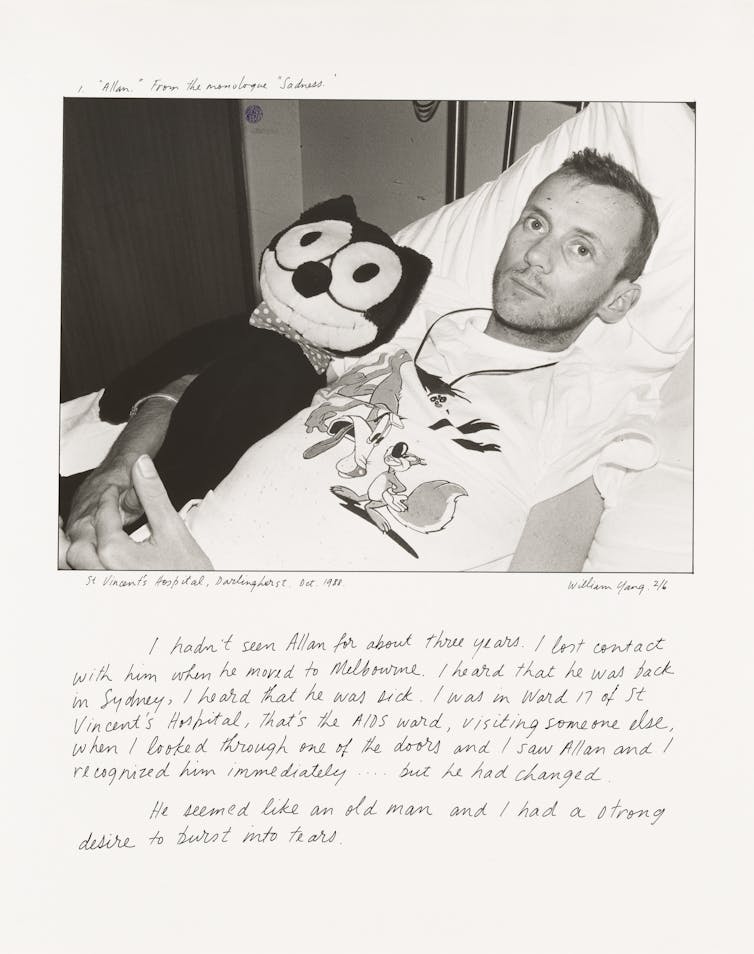

Visibility as a political strategy comes to the fore in the powerful sequence “Allan” from the 1990s Sadness project. Allan’s life is memorialised as Yang traces his friend and ex-lover’s physical decline from a HIV-related illness, poignantly reminding us of the terrifying devastation wreaked by AIDS on Sydney’s gay community during this time.

The viewer is allowed into the intensely private world of death and dying as Yang chronicles the final 12 months of Allan’s life with dignity and tenderness.

William Yang, Allan, no.1 (from the ‘Sadness’ series) 1990. Gelatin silver photographs, ink / 21 photographs, 51 x 41cm (sheet, each). Purchased 2000.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

© William Yang.

William Yang, Allan, no.1 (from the ‘Sadness’ series) 1990. Gelatin silver photographs, ink / 21 photographs, 51 x 41cm (sheet, each). Purchased 2000.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

© William Yang.

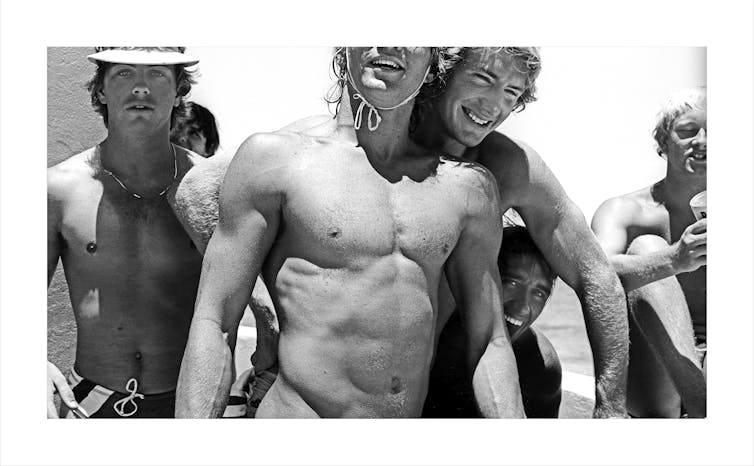

Yang is at his playful best when he disrupts stereotypical ideas of nationhood. For generations, the beach and its lifesavers have occupied a symbolic position in Australian’s national consciousness.

In one of the key images of the exhibition, lifeguards from Sydney’s Tamarama beach are captured by Yang’s desirous gaze, forcing the viewer to consider the heterosexual framing of national identity.

William Yang, Tamarama Lifesavers 1981.

Inkjet print on Hahnemühle Fine Art Pearl.

Image courtesy the artist.

© William Yang

William Yang, Tamarama Lifesavers 1981.

Inkjet print on Hahnemühle Fine Art Pearl.

Image courtesy the artist.

© William Yang

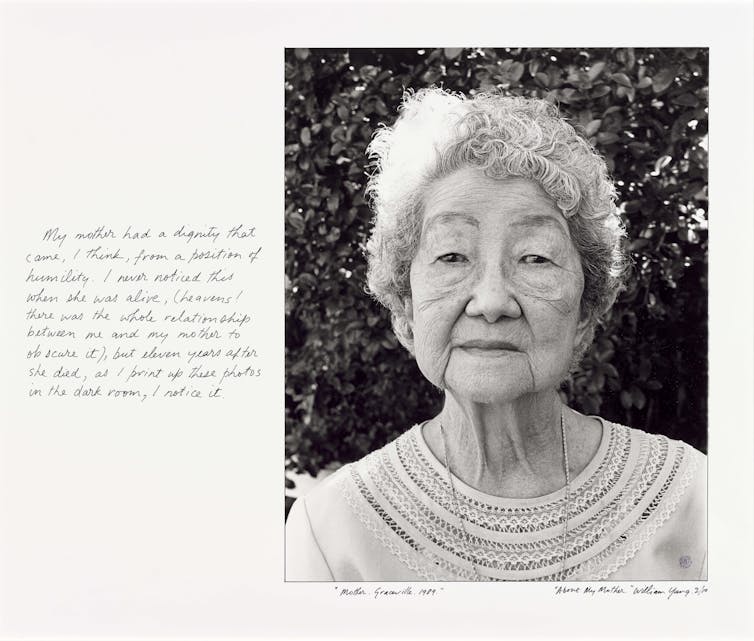

Family history has also preoccupied Yang over the decades. The series “About my mother” is both affectionate and loving as he retrospectively documents the relationship with his mother Emma after her death.

William Yang, 1943, Mother. Graceville. 1989. (from About my mother portfolio) 2003, Gelatin silver photograph ed. 2/10.

51.3 x 61.1cm. Purchased 2004. Queensland Art Gallery

Foundation Grant.

© William Yang. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

William Yang, 1943, Mother. Graceville. 1989. (from About my mother portfolio) 2003, Gelatin silver photograph ed. 2/10.

51.3 x 61.1cm. Purchased 2004. Queensland Art Gallery

Foundation Grant.

© William Yang. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Again, text is important as Yang records his memories and observations. Some are candid and fun; others record Emma’s unwillingness to acknowledge Yang’s sexual identity. Yang reflects:

My mother had a dignity that came, I think, from a position of humility: I never noticed this when she was alive (heavens! there was the whole relationship between me and my mother to obscure it), but eleven years after she died, as I print up these photos in the dark room, I notice it.

One of the surprising aspects of the exhibition is Yang’s landscape photography.

Frequently, Yang will insert himself into these landscapes. Working in a large-scale format, these images suggest Yang is still trying to make sense of his identity and his relationship with the physical environment of far north Queensland that shaped his childhood.

William Yang, Australia, 1943, Return to the place of childhood. Dimbulah 2016. Inkjet print on Ilford Galerie Smooth Cotton.

Rag. Image courtesy: The artist

© William Yang.

William Yang, Australia, 1943, Return to the place of childhood. Dimbulah 2016. Inkjet print on Ilford Galerie Smooth Cotton.

Rag. Image courtesy: The artist

© William Yang.

William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen is showing at the Queensland Art Gallery until August 22.

Authors: Chari Larsson, Lecturer of art history, Griffith University