Sunshine Super Girl is destined to become a legacy piece of Australian theatre

- Written by Liza-Mare Syron, Indigenous Scientia Senior Lecturer, UNSW

Review: Sunshine Super Girl, written and directed by Andrea James, Performing Lines and Sydney Festival

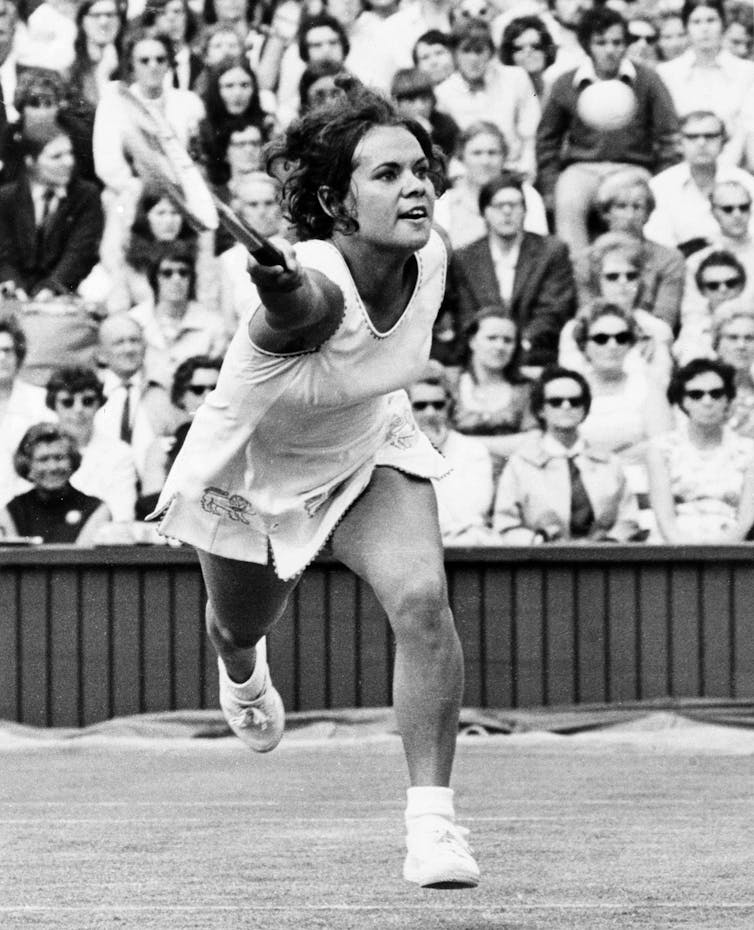

Evonne Goolagong Cawley is one of Australia’s greatest sportspeople. She was the top woman tennis player in the world in 1971 (a feat she repeated in 1976), becoming the first Indigenous woman to achieve national and international prominence.

Born in Griffith, New South Wales, Goolagong Cawley ended her career with 82 singles titles, including seven Grand Slam titles. At just 19, she won the French Open singles crown and the Australian Open doubles championships (with Margaret Court), and in 1980 she became the first woman to win Wimbledon as a mother since 1914.

Sunshine Super Girl, written and directed by Yorta Yorta/Gunnaikurnai playwright Andrea James, brings the biography of the Wiradjuri tennis sensation to the stage.

The task of translating a biography to the stage is a difficult one and James constructs a chronological arrangement focusing on key transition periods in Goolagong Cawley’s life. A passionate tennis fan, James is the right person to pen this story for the stage, weaving this history in a way that is both intimate and personal.

Tuuli Narkle and Luke Carrol hold this story gently and with confidence.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

Tuuli Narkle and Luke Carrol hold this story gently and with confidence.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

Created from interviews with Goolagong Cawley - who was very much part of the play’s development — Sunshine Super Girl is a moving account of Goolagong Cawley’s life from her small town tennis competitions in Barellan, NSW, to becoming a world sensation and Grand Slam champion.

A love story at its heart

One by one, the actors enter, warming up in their white tennis outfits. Taking her place on top of the umpires chair, Evonne (Yued/Willman actor Tuuli Narkle) throws a fishing line into the Murrumbidgee river.

Narkle is a little tentative in her opening performance, given only two weeks to rehearse after Murrawarri actor Katie Beckett was injured. But with renowned Wiradjuri actor Luke Carrol by her side playing both local tennis mentor Bill Kurtzman and her professional coach Vic Edwards, the pair hold this story gently and with confidence.

Sunshine Super Girl uses both text and dance to tell the story.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

Sunshine Super Girl uses both text and dance to tell the story.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

Dancers Jax Compton (Wuthathi), Katina Olsen (Waka Waka/Kombamerri) and Kyle Shilling (Bundjalung) provide a seamless choreography (by Olsen and Vicki Van Hout) of tennis postures deconstructing each pose and stance of the body in its attack of the ball, while also performing various sideline characters.

Goolagong Cawley’s parents, siblings, and tennis opponents (Martina Navratilova, Chris Everett Lloyd and Margaret Court) are thinly sketched at best. But Compton’s satirical portrayal of John Newcombe as the reigning men’s champion dancing at the “Wimbledon Ball” is a scene stealer.

Dramatic moments in the play mostly culminate on court, but at the heart of Sunshine Super Girl is the love story between Evonne and Roger Cawley (played by Shilling), a romance that spans the globe and culminates in a return to country.

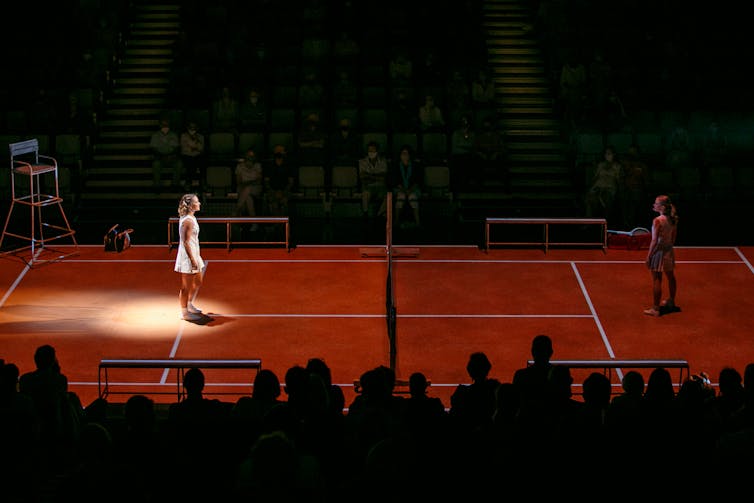

Staged in the traverse, Sunshine Super Girl mimics sitting court-side at a tennis match.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

Staged in the traverse, Sunshine Super Girl mimics sitting court-side at a tennis match.

Yaya Stempler/Sydney Festival

The tennis court set, designed in the traverse by Mel Lertz, is simple but effective and brought to life by video designer Mic Gruchy’s animated projections.

Karen Norris’ lighting is subtle with light pink and blue tones suggesting the reticent “rock star” status of Goolagong Cawley, but flashing camera lights regularly intrude the softness of this gentle ambience.

Strength of spirit

Having a writer as the show director is always a precarious choice, but not unusual in Indigenous theatre. Having creative control over how an Indigenous story is developed and presented is a key feature of what makes a work Indigenous.

The theatrical framework in which we work is mostly determined by Western and European understandings of theatre narrative structures, plot, characters, stage elements and language. In this, the role of the Indigenous director or playwright is often to provide and support a way of working that embeds Indigenous ways of knowing, seeing, and doing in performance.

Evonne Goolagong Cawley at Wimbledon in 1971, where she would win her first Wimbledon, weeks after winning the French Open.

AP Photo, File

Evonne Goolagong Cawley at Wimbledon in 1971, where she would win her first Wimbledon, weeks after winning the French Open.

AP Photo, File

James’ direction is sparse, allowing for the depth and breadth of Goolagong Cawley’s life to be magnified on stage. The more serious moments in the play are tempered by comic relief, reflecting a common cultural response to the casual racism of Australian media and society many Indigenous peoples face.

In attending the opening night performance, I was saddened by the lack of First peoples in the audience. I understand these events are for patrons and supporters of the festival, but I believe having First peoples present at the telling of one of their own stories provides a different experience than one where they are absent. First peoples audiences hold these stories and can offer an extraordinary generosity of attendance.

Sunshine Super Girl is destined to become a legacy piece, one that celebrates our history, reflects on our struggle for equality, and shows how the spirit can overcome in spectacular ways.

Sunshine Super Girl is at Sydney Festival until January 17.

Authors: Liza-Mare Syron, Indigenous Scientia Senior Lecturer, UNSW