who's spending and who’s winning on social media ahead of New Zealand's election

- Written by Sommer Kapitan, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, Auckland University of Technology

If social media engagement rates determined which parties form the next government, New Zealand’s parliament would soon look a lot different.

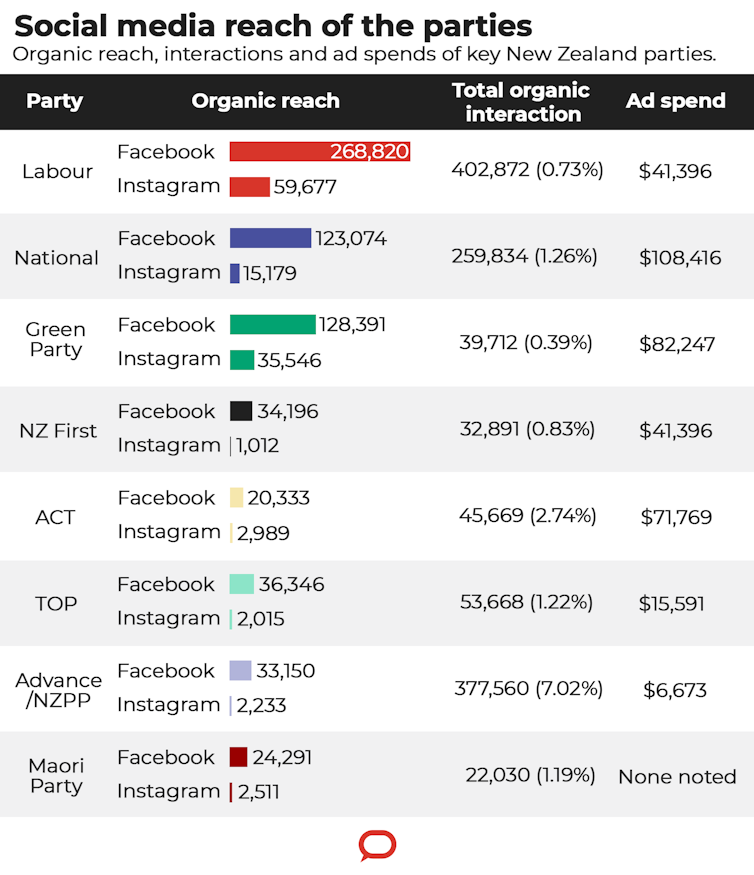

With its daily social media interactions commanding an average 7.7% engagement rate, Advance NZ (incorporating the NZ Public Party) would be streets ahead of Labour and National.

Opposing the COVID-19 Public Health Response Act 2020, 5G and the United Nations, and promoting anti-lockdown protests, might only get them to 1% in opinion polls — but it is a winning formula online.

Advance NZ’s livestreamed anti-lockdown march in August netted 255,600 views — 86% of them generated by only 4,793 people who shared the posted video.

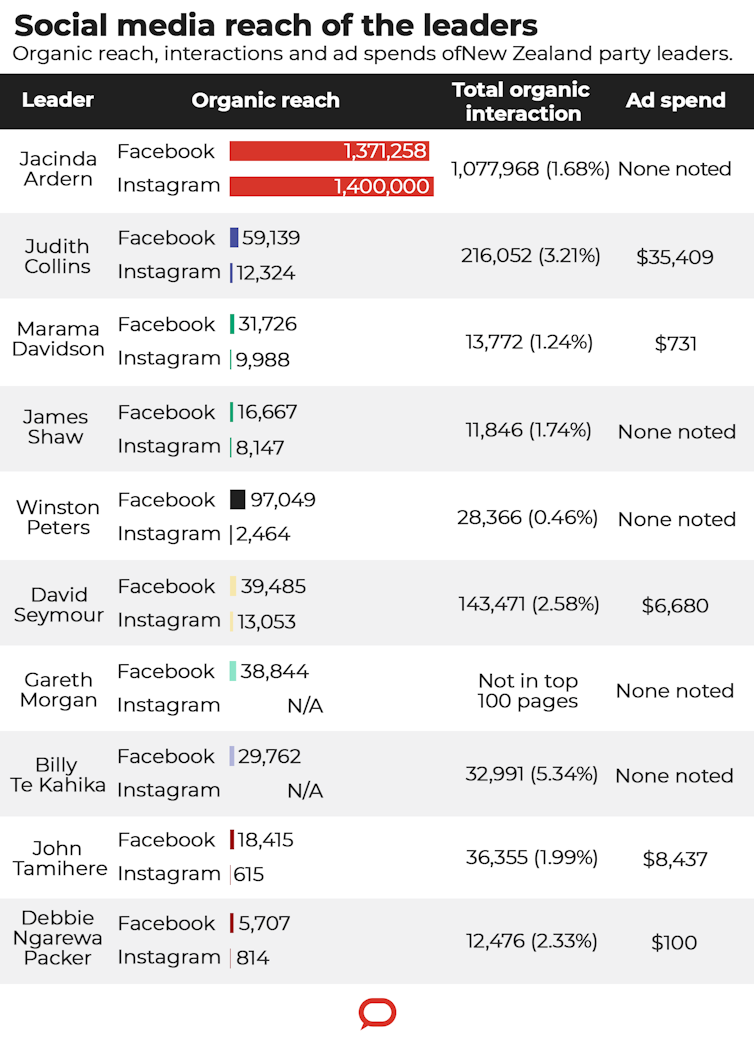

That’s a higher engagement rate than many posts by the acknowledged Facebook champion of New Zealand politics, the prime minister and Labour leader, Jacinda Ardern, whose own posts routinely attract between 120,000 and 500,000 views.

Politics in the attention economy

Across the political spectrum, parties have seen the greatest boost in visibility when they post about hot-button issues: taxation, lockdowns, economic stress, mask wearing — even tobacco prices.

A photo meme of New Zealand First leader Winston Peters pledging to remove tobacco excise tax was among the highest-performing posts, gaining 24 times the party’s usual number of comments, likes, shares and views.

The platform algorithms reward posts that outperform a party page’s usual engagement rates. In a kind of snowball effect, high-performing posts are pushed higher into news feeds and deeper into the minds of voters.

Social media algorithms are proprietary and tweaked often. But their purpose is clear — to read the user’s searches and interactions in order to serve them more related content and keep them continually engaged.

With this persuasive power built into the technology and our attention now a commodity to be bought and sold, no politician can ignore social media nowadays.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Organic vs paid media

In New Zealand from July to September 25, there were 9,537 paid advertisements on Facebook and Instagram related to social issues, elections and politics, costing a total of $NZ 1,054,713.

Parties are particularly paying for attention when their content has limited organic reach.

Labour and Jacinda Ardern have the greatest organic reach, with 1.6 million Facebook fans combined (the lion’s share being Ardern’s). The party spent only $41,396 on posts in one 30-day period ending in September.

Read more:

We need a code to protect our online privacy and wipe out 'dark patterns' in digital design

By contrast, National and its leader Judith Collins lack organic reach. With only 180,000 fans across their Facebook pages, they need to spend to keep up — $143,825 in the same 30-day period.

Of that, $35,000 was devoted to a massive push for people seeing Collins’ social media advertisements to “like my page to stay up to date”. Ultimately, the strategy is about boosting party votes and building greater organic reach in future.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Organic vs paid media

In New Zealand from July to September 25, there were 9,537 paid advertisements on Facebook and Instagram related to social issues, elections and politics, costing a total of $NZ 1,054,713.

Parties are particularly paying for attention when their content has limited organic reach.

Labour and Jacinda Ardern have the greatest organic reach, with 1.6 million Facebook fans combined (the lion’s share being Ardern’s). The party spent only $41,396 on posts in one 30-day period ending in September.

Read more:

We need a code to protect our online privacy and wipe out 'dark patterns' in digital design

By contrast, National and its leader Judith Collins lack organic reach. With only 180,000 fans across their Facebook pages, they need to spend to keep up — $143,825 in the same 30-day period.

Of that, $35,000 was devoted to a massive push for people seeing Collins’ social media advertisements to “like my page to stay up to date”. Ultimately, the strategy is about boosting party votes and building greater organic reach in future.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Reach and reinforcement

But even smaller parties have outspent Labour. The Greens paid $82,000 for social advertising in the same period.

However, Greens Auckland Central candidate Chloe Swarbrick (who has a bigger social following than party co-leaders James Shaw or Marama Davidson) went organically viral with a simple photo of herself wearing a vintage party jumper.

Replica garments were rushed into production and sold out overnight on the party’s fundraising site.

So, social media do work, as ACT and its leader, David Seymour, would no doubt also attest. Having spent $78,000 to promote their “Change your future” bus tour and “Holding the other parties accountable” message, the party is climbing in the polls.

And despite its organic strength, Advance NZ has spent nearly $7,000 on social media. Half of that was dedicated to boosting numbers at the anti-lockdown protests, but such spending is also clearly designed to reach voters who aren’t already fans or friends of fans.

Cultivating reality

The benign view is that social channels allow parties to stay in the conversations and thoughts of voters. Voters in return become more connected to politicians and informed on the issues they care about.

But because of the way those algorithms work, voters may rarely see the other side of policies and issues. Instead, those first clicks, views and interactions lead down the rabbit hole and create filter bubbles.

Read more:

With the election campaign underway, can the law protect voters from fake news and conspiracy theories?

Filter bubbles have been blamed for slowly polarising audiences, causing gradual changes in voter behaviour and perception. This is a vastly different political sphere than existed even five years ago.

For example, anyone following only certain politicians might not have known that several social posts misrepresenting Ardern’s comments about farming in the first TV leaders’ debate had been subsequently fact-checked and debunked.

Over time, the filter bubble makes room for fake news to churn inside these echo chambers where users often fail to fact-check content. Misinformation thrives on repetition and familiarity.

But is there evidence that digital messaging influences voting behaviour? Yes, according to at least one major US study, especially when shared with friends and family. Such forms of social transmission seem more effective than politicians’ own use of social media.

If attitudes cultivated online translate into real-world voting behaviour, then Advance NZ may be merely a forerunner of what’s to come in New Zealand.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Reach and reinforcement

But even smaller parties have outspent Labour. The Greens paid $82,000 for social advertising in the same period.

However, Greens Auckland Central candidate Chloe Swarbrick (who has a bigger social following than party co-leaders James Shaw or Marama Davidson) went organically viral with a simple photo of herself wearing a vintage party jumper.

Replica garments were rushed into production and sold out overnight on the party’s fundraising site.

So, social media do work, as ACT and its leader, David Seymour, would no doubt also attest. Having spent $78,000 to promote their “Change your future” bus tour and “Holding the other parties accountable” message, the party is climbing in the polls.

And despite its organic strength, Advance NZ has spent nearly $7,000 on social media. Half of that was dedicated to boosting numbers at the anti-lockdown protests, but such spending is also clearly designed to reach voters who aren’t already fans or friends of fans.

Cultivating reality

The benign view is that social channels allow parties to stay in the conversations and thoughts of voters. Voters in return become more connected to politicians and informed on the issues they care about.

But because of the way those algorithms work, voters may rarely see the other side of policies and issues. Instead, those first clicks, views and interactions lead down the rabbit hole and create filter bubbles.

Read more:

With the election campaign underway, can the law protect voters from fake news and conspiracy theories?

Filter bubbles have been blamed for slowly polarising audiences, causing gradual changes in voter behaviour and perception. This is a vastly different political sphere than existed even five years ago.

For example, anyone following only certain politicians might not have known that several social posts misrepresenting Ardern’s comments about farming in the first TV leaders’ debate had been subsequently fact-checked and debunked.

Over time, the filter bubble makes room for fake news to churn inside these echo chambers where users often fail to fact-check content. Misinformation thrives on repetition and familiarity.

But is there evidence that digital messaging influences voting behaviour? Yes, according to at least one major US study, especially when shared with friends and family. Such forms of social transmission seem more effective than politicians’ own use of social media.

If attitudes cultivated online translate into real-world voting behaviour, then Advance NZ may be merely a forerunner of what’s to come in New Zealand.

Authors: Sommer Kapitan, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, Auckland University of Technology