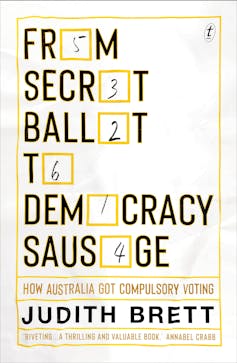

From secret ballot to democracy sausage

- Written by Judith Brett, Emeritus Professor of Politics, La Trobe University

This is an edited extract from Judith Brett’s new book, From secret ballet to democracy sausage: how Australia got compulsory voting, Text Publishing, 2019.

Not many countries compel their citizens to vote, but Australia is one. Voting is compulsory in 19 of the world’s 166 electoral democracies and only nine strictly enforce it. None of Europe’s most influential democracies has it, and none of the countries in the mainstream of Australia’s political development: not the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, New Zealand or Ireland.

People from our sister democracies are often astonished that Australians are compelled to turn up to vote: it seems an affront to freedom. We in reply are appalled at their low turnouts and the election of leaders and governments by a minority of voters.

In the 2016 American presidential election, the percentage turnout was in the high fifties. Donald Trump did not have the support of the majority of voters, but neither would Hillary Clinton had she won.

Britain’s disastrous 2016 decision to leave the European Union was carried by a slim majority of the 72.2% of voters who turned out. At Canada’s 2015 election, which brought Justin Trudeau to power, the turnout of 68.3% was the highest in 20 years.

These are percentages of registered voters, not of all those eligible to vote. In none of these countries is it compulsory to be on the electoral roll. In Australia, registration has been compulsory since 1911. Turnout in Australian elections is always above 90% of registered voters, and in the high eighties of those eligible to enrol.

It has been compulsory to vote in Australian federal elections since 1924, when a private member’s bill passed through both houses in a single day with scarcely any debate. Geoffrey Sawer, doyen of Australia’s legal historians, famously wrote:

No major departure in the federal political system had ever been made in so casual a fashion.

Sawer was wrong: the ease of the bill’s passage was not because of lack of attention. Rather, it was uncontroversial because it expressed the political culture that had developed in Australia since the middle of the 19th century, when the colonies became self-governing.

This political culture was majoritarian and bureaucratic. Australians wanted their governments to have the support of the majority of electors, they preferred their elections to be orderly and they were happy for them to be run by government officials. By the time voting was made compulsory for federal elections, the arguments for and against had been thoroughly aired, and for 13 years it had been compulsory for all eligible adults to be on the electoral roll. The paucity of debate Sawer noted was not a sign of indifference but of relaxed acceptance of an outcome long in the making.

Support for compulsory voting among Australians is consistently high. Since the earliest opinion polls on the matter, in 1943, it has never been less than 60%. Support grew in the decades following the second world war and since 1967, it has bounced around in the 70% range. The lowest was 64% in 1987, and the highest 77% in 1969 and 2007, both elections in which there was a surge to Labor.

Respondents were also asked if they would vote if it were voluntary and more than 80% said Yes. They were telling the truth. This is around the number who took part in the non-compulsory same-sex marriage survey in 2017.

In the 2016 American presidential election, the percentage turnout was in the high fifties. Donald Trump did not have the support of the majority of voters, but neither would Hillary Clinton had she won.

Britain’s disastrous 2016 decision to leave the European Union was carried by a slim majority of the 72.2% of voters who turned out. At Canada’s 2015 election, which brought Justin Trudeau to power, the turnout of 68.3% was the highest in 20 years.

These are percentages of registered voters, not of all those eligible to vote. In none of these countries is it compulsory to be on the electoral roll. In Australia, registration has been compulsory since 1911. Turnout in Australian elections is always above 90% of registered voters, and in the high eighties of those eligible to enrol.

It has been compulsory to vote in Australian federal elections since 1924, when a private member’s bill passed through both houses in a single day with scarcely any debate. Geoffrey Sawer, doyen of Australia’s legal historians, famously wrote:

No major departure in the federal political system had ever been made in so casual a fashion.

Sawer was wrong: the ease of the bill’s passage was not because of lack of attention. Rather, it was uncontroversial because it expressed the political culture that had developed in Australia since the middle of the 19th century, when the colonies became self-governing.

This political culture was majoritarian and bureaucratic. Australians wanted their governments to have the support of the majority of electors, they preferred their elections to be orderly and they were happy for them to be run by government officials. By the time voting was made compulsory for federal elections, the arguments for and against had been thoroughly aired, and for 13 years it had been compulsory for all eligible adults to be on the electoral roll. The paucity of debate Sawer noted was not a sign of indifference but of relaxed acceptance of an outcome long in the making.

Support for compulsory voting among Australians is consistently high. Since the earliest opinion polls on the matter, in 1943, it has never been less than 60%. Support grew in the decades following the second world war and since 1967, it has bounced around in the 70% range. The lowest was 64% in 1987, and the highest 77% in 1969 and 2007, both elections in which there was a surge to Labor.

Respondents were also asked if they would vote if it were voluntary and more than 80% said Yes. They were telling the truth. This is around the number who took part in the non-compulsory same-sex marriage survey in 2017.

Australians take their right to vote seriously. Even though the marriage equality postal vote was not compulsory, about 80% of eligible voters lodged a ballot.

AAP/Danny Casey

When it was first introduced, the penalty for not voting was high: two pounds, or $160 in today’s money. In 2017, the fine for not voting in a federal election without adequate reason was only $20, scarcely enough to compel a high turnout. It is also permissible simply to turn up to the polling booth, have one’s name crossed off and leave the ballot paper blank, though surprisingly few take this option. Most invalid votes are the results of confusion.

How did compulsory voting become so entrenched in Australia’s political culture and why is it that, alone among English-speaking democracies, Australia compels its citizens to vote?

Compulsory voting and enrolment are not the only distinctive features of our elections. We vote on Saturdays, the United Kingdom on Thursdays because it was once market day, and the United States on Tuesdays. We have preferential voting, whereas the norm is firstpast-the-post, in which the candidate with the most votes wins. We can vote at any electoral booth in our home state, as well as interstate and at our overseas embassies and consulates. And our elections are run by government bureaucrats, according to uniform rules, with political parties and politicians at arm’s-length.

Australia’s embrace of compulsory voting tells us a great deal about the way our history has shaped our political culture. When he was president, Barack Obama praised Australia’s mandatory voting and said that if everybody in the United States voted:

it would completely change the political map in this country because the people who tend not to vote are young. They are lower-income. They are skewed more heavily towards immigrant groups and minority groups.

Mandatory voting would counteract the power of money in determining elections, he said, and encourage lawmakers to make it easier rather than harder for people to vote. Obama stopped short, however, of calling for a change in the law. No doubt he knew that this would have little chance in a country which places a higher value on the liberty of the individual than on the collective good. Too many would argue that it was undemocratic, authoritarian, an infringement of an individual’s rights.

By the time the Australian colonies were establishing their political institutions, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, the British parliament had well and truly defeated the autocratic monarchs. Britain was a constitutional monarchy, with legislative and executive power firmly in the hands of the parliament and the monarch reduced to a largely ceremonial role.

The franchise was expanding, and the British government, not wanting to lose its Australian colonies as it had its American, ruled them with a light touch. When the colonies started politely to request self-government, it was granted. Where John Locke was the foundational thinker for the United States, for Australia it was the philosopher and political reformer Jeremy Bentham.

Bentham rejected the idea of natural or divinely given rights that precede the establishment of government. He argued instead that rights are created by law; that without government and law there are no rights. Government first, then rights.

He also believed that government should be guided by what he called the principle of utility: that government policies and actions should advance the greatest happiness for the greatest number, with each person counting as one. British government in the early 19th century was patently not doing this. Power was in the hands of a small landed elite, who governed for the interests of their class while the lives of many were blighted by want and misery. Bentham wrote lengthy accounts of schemes for the reform of Britain’s political and legal institutions, including for manhood suffrage (the right for all men to vote regardless of property or income) and the secret ballot.

Bentham held a much more expansive view of the possibilities of government action than did America’s founding fathers, with their elaborate checks and balances, and this suited the circumstances of the Australian colonies. New colonies demand “ample government”, wrote Edward Gibbon Wakefield, whose ideas on systematic colonisation inspired the establishment of South Australia. Australia’s colonies needed roads, bridges, ports, railways and irrigation works, and later gas, electricity, sewerage and the telegraph — in short, all the infrastructure required for a modern exporting economy — and it was provided by the government.

What’s more, for the first 100 years or so, Australian taxpayers didn’t even have to pay much for the services government provided. The threat of taxation, a major motivator of liberalism’s defence of individual rights and arguments for small government, was largely missing. The British government paid for the early Australian governments. Remembering the American colonies’ revolt over taxation without representation, it decided not to tax the Australian settlers. Britain would gain its economic return instead from increased trade and investment opportunities.

Nor did Australia have to pay for its own defence, as this too was provided by the British government. With little taxation, why would people want to limit government expenditure on services that benefited them?

“So,” writes the historian John Hirst, “the function of government changed in Australia: it was not primarily to keep order within and defeat enemies without; it was a resource which settlers could draw on to make money.” The paternalism of the Australian state is based on the circumstances of our settlement.

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Australia led the world in electoral reform.

It was a laboratory for new ideas about democracy, and new methods of achieving them. Property qualifications were all but gone for men for lower-house elections in the populous south-eastern colonies by the end of the 1850s. Colonial politicians had invented the ballot paper and the compartmentalised polling booth to ensure secret voting, and the Australian ballot, as it became known, quickly spread around the world.

In 1894, South Australian women won the right to vote, a year after women in New Zealand, along with the right to stand for parliament, which was a world-first. South Australia also established the first non-partisan, government-run electoral office to manage elections.

Two of our innovations, though, have found few followers: compulsory voting and our rejection of first-past-the-post in favour of preferential voting. Few countries use preferential voting, and then only for some elections. We use it for them all.

Preferential voting is as distinctively Australian as compulsory voting. Both ensure that the governments we elect have the support of the majority of voters.

At the end of the 19th century, after the colonial politicians had hammered out a constitution for a new, federated nation, men (and women in South and Western Australia) voted on whether to accept it. The question was simple:

Are you in favour of the proposed Federal Constitutional Bill? Yes or No.

In 1898, the answer was No, but, after some amendments, at a second referendum a year later it was Yes, and the new Commonwealth was proclaimed on New Year’s Day, 1901.

The elections for the first federal parliament were run according to the laws of the states; once elected, the new parliament had to settle on how future federal elections would be run and who would be eligible to vote.

Australians take their right to vote seriously. Even though the marriage equality postal vote was not compulsory, about 80% of eligible voters lodged a ballot.

AAP/Danny Casey

When it was first introduced, the penalty for not voting was high: two pounds, or $160 in today’s money. In 2017, the fine for not voting in a federal election without adequate reason was only $20, scarcely enough to compel a high turnout. It is also permissible simply to turn up to the polling booth, have one’s name crossed off and leave the ballot paper blank, though surprisingly few take this option. Most invalid votes are the results of confusion.

How did compulsory voting become so entrenched in Australia’s political culture and why is it that, alone among English-speaking democracies, Australia compels its citizens to vote?

Compulsory voting and enrolment are not the only distinctive features of our elections. We vote on Saturdays, the United Kingdom on Thursdays because it was once market day, and the United States on Tuesdays. We have preferential voting, whereas the norm is firstpast-the-post, in which the candidate with the most votes wins. We can vote at any electoral booth in our home state, as well as interstate and at our overseas embassies and consulates. And our elections are run by government bureaucrats, according to uniform rules, with political parties and politicians at arm’s-length.

Australia’s embrace of compulsory voting tells us a great deal about the way our history has shaped our political culture. When he was president, Barack Obama praised Australia’s mandatory voting and said that if everybody in the United States voted:

it would completely change the political map in this country because the people who tend not to vote are young. They are lower-income. They are skewed more heavily towards immigrant groups and minority groups.

Mandatory voting would counteract the power of money in determining elections, he said, and encourage lawmakers to make it easier rather than harder for people to vote. Obama stopped short, however, of calling for a change in the law. No doubt he knew that this would have little chance in a country which places a higher value on the liberty of the individual than on the collective good. Too many would argue that it was undemocratic, authoritarian, an infringement of an individual’s rights.

By the time the Australian colonies were establishing their political institutions, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, the British parliament had well and truly defeated the autocratic monarchs. Britain was a constitutional monarchy, with legislative and executive power firmly in the hands of the parliament and the monarch reduced to a largely ceremonial role.

The franchise was expanding, and the British government, not wanting to lose its Australian colonies as it had its American, ruled them with a light touch. When the colonies started politely to request self-government, it was granted. Where John Locke was the foundational thinker for the United States, for Australia it was the philosopher and political reformer Jeremy Bentham.

Bentham rejected the idea of natural or divinely given rights that precede the establishment of government. He argued instead that rights are created by law; that without government and law there are no rights. Government first, then rights.

He also believed that government should be guided by what he called the principle of utility: that government policies and actions should advance the greatest happiness for the greatest number, with each person counting as one. British government in the early 19th century was patently not doing this. Power was in the hands of a small landed elite, who governed for the interests of their class while the lives of many were blighted by want and misery. Bentham wrote lengthy accounts of schemes for the reform of Britain’s political and legal institutions, including for manhood suffrage (the right for all men to vote regardless of property or income) and the secret ballot.

Bentham held a much more expansive view of the possibilities of government action than did America’s founding fathers, with their elaborate checks and balances, and this suited the circumstances of the Australian colonies. New colonies demand “ample government”, wrote Edward Gibbon Wakefield, whose ideas on systematic colonisation inspired the establishment of South Australia. Australia’s colonies needed roads, bridges, ports, railways and irrigation works, and later gas, electricity, sewerage and the telegraph — in short, all the infrastructure required for a modern exporting economy — and it was provided by the government.

What’s more, for the first 100 years or so, Australian taxpayers didn’t even have to pay much for the services government provided. The threat of taxation, a major motivator of liberalism’s defence of individual rights and arguments for small government, was largely missing. The British government paid for the early Australian governments. Remembering the American colonies’ revolt over taxation without representation, it decided not to tax the Australian settlers. Britain would gain its economic return instead from increased trade and investment opportunities.

Nor did Australia have to pay for its own defence, as this too was provided by the British government. With little taxation, why would people want to limit government expenditure on services that benefited them?

“So,” writes the historian John Hirst, “the function of government changed in Australia: it was not primarily to keep order within and defeat enemies without; it was a resource which settlers could draw on to make money.” The paternalism of the Australian state is based on the circumstances of our settlement.

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Australia led the world in electoral reform.

It was a laboratory for new ideas about democracy, and new methods of achieving them. Property qualifications were all but gone for men for lower-house elections in the populous south-eastern colonies by the end of the 1850s. Colonial politicians had invented the ballot paper and the compartmentalised polling booth to ensure secret voting, and the Australian ballot, as it became known, quickly spread around the world.

In 1894, South Australian women won the right to vote, a year after women in New Zealand, along with the right to stand for parliament, which was a world-first. South Australia also established the first non-partisan, government-run electoral office to manage elections.

Two of our innovations, though, have found few followers: compulsory voting and our rejection of first-past-the-post in favour of preferential voting. Few countries use preferential voting, and then only for some elections. We use it for them all.

Preferential voting is as distinctively Australian as compulsory voting. Both ensure that the governments we elect have the support of the majority of voters.

At the end of the 19th century, after the colonial politicians had hammered out a constitution for a new, federated nation, men (and women in South and Western Australia) voted on whether to accept it. The question was simple:

Are you in favour of the proposed Federal Constitutional Bill? Yes or No.

In 1898, the answer was No, but, after some amendments, at a second referendum a year later it was Yes, and the new Commonwealth was proclaimed on New Year’s Day, 1901.

The elections for the first federal parliament were run according to the laws of the states; once elected, the new parliament had to settle on how future federal elections would be run and who would be eligible to vote.

Celebrating federation in Australia, 1901.

Museum of Australian Democracy

The federal Franchise Act and the federal Electoral Act were both passed in 1902, the first quickly, the second after extensive debate. The disenfranchisement of Australia’s Indigenous people, even as white women were being given the vote, is notorious, but in most other ways these two acts were astonishingly democratic and they laid the foundations of our electoral system.

There were crucial developments in 1911, when Labor made registration compulsory and introduced Saturday voting; in 1918, when preferential voting came in; and in 1924, when voting too was made compulsory.

Australia was born not on the battlefield but at the ballot box. Sixteen years after the 1899 referendum which accepted the constitution, and 14 after the Commonwealth was proclaimed in 1901, the nation was born again, on the Gallipoli Peninsula, as the mettle of its men was tested by war.

The Anzac Legend is a core Australian foundation myth. But we need more than stories of blood and heroic sacrifice, compelling as these will always be, if we are to understand our peacetime nation. The story of how we got compulsory voting is no less definitive of who we are.

Celebrating federation in Australia, 1901.

Museum of Australian Democracy

The federal Franchise Act and the federal Electoral Act were both passed in 1902, the first quickly, the second after extensive debate. The disenfranchisement of Australia’s Indigenous people, even as white women were being given the vote, is notorious, but in most other ways these two acts were astonishingly democratic and they laid the foundations of our electoral system.

There were crucial developments in 1911, when Labor made registration compulsory and introduced Saturday voting; in 1918, when preferential voting came in; and in 1924, when voting too was made compulsory.

Australia was born not on the battlefield but at the ballot box. Sixteen years after the 1899 referendum which accepted the constitution, and 14 after the Commonwealth was proclaimed in 1901, the nation was born again, on the Gallipoli Peninsula, as the mettle of its men was tested by war.

The Anzac Legend is a core Australian foundation myth. But we need more than stories of blood and heroic sacrifice, compelling as these will always be, if we are to understand our peacetime nation. The story of how we got compulsory voting is no less definitive of who we are.

Authors: Judith Brett, Emeritus Professor of Politics, La Trobe University

Read more http://theconversation.com/book-extract-from-secret-ballot-to-democracy-sausage-112695