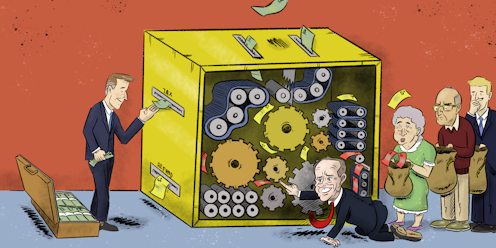

Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation. And what's "retiree tax"?

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

You’re forgiven for being confused.

Newspapers need to economise on words. Television and radio reporters need to economise on seconds. So they use shorthand: words like “dividend imputation”, “franking credits”, and yes, “retiree tax”

Which is fine if you already know what they mean, and pretty fine if you don’t, because you probably don’t need to. They speed things along.

Until now. Suddenly, because of their prominence in the upcoming election campaign, we are going to have to know what they mean. We are even going to have to know that one of them doesn’t mean what it seems to mean. The election might depend on it.

So here goes:

Taxable profits

If a company’s income exceeds its expenses, it has made a profit, which in ordinary circumstances is taxed at the leglislated rate, which for big companies such as Telstra and the big banks is 30 cents in the dollar.

Dividends

After the tax is taken out, companies can pay some of what’s left to shareholders as a dividend, one for each share.

Last September Telstra paid shareholders a dividend of 15.5 cents per share. The previous March it was 11 cents.

Income tax

Australians pay tax on what they earn, unless the income is classified as not taxable or is below the A$18,200 tax-free threshold. The marginal rate (the rate on extra income) climbs with income, so that anyone earning more than A$180,000 (the top threshold) pays 45 cents on each extra dollar earned.

Dividends are taxable and so are taxed along with other income.

Dividend imputation

In 1987 in what he hailed as a world first, Labor treasurer Paul Keating introduced a rebate for each each tax-paying dividend recipient.

Taken off their tax would be the company tax the company had paid on the part of the profit that had been handed to them as a dividend.

It “would greatly reduce the existing bias in the tax system which taxed interest income once, but dividend income twice”.

Here’s how it was to work at today’s tax rates.

Jill owns 1,000 Telstra shares

Over the period of a year she gets dividends of A$265

To provide them, Telstra made a profit of A$379 on which it paid A$114 tax

Jill pays tax on the full $379 but gets a credit of A$114 that can be taken off any other tax she owes that year

As with other tax credits, it can be used to cut Jill’s tax bill as far as zero, but not to turn it negative. It can’t be handed to her in cash.

As Keating put it, the tax paid at the company level would be imputed, or allocated to shareholders by means of imputation credits.

But not to all of them. Non-resident (overseas) shareholders couldn’t get them, and nor could shareholders whose dividends hadn’t been franked.

Franking credits

As Keating explained, the tax credit only applied to the extent to which full Australian company tax had been paid; to the extent to which the dividends had been franked (stamped) to indicate that tax had been paid.

Not every company pays the full 30 cents in the dollar in every year. Often it is carrying forward previous losses. Only dividends from profits on which full tax had actually been paid were to be marked “fully franked”. Dividends on which tax had been partly paid were to be marked “partly franked”.

Fully franked dividends became sought after, because they brought with them the biggest franking credits. In a useful side effect, dividend imputation encouraged companies that wanted to look after their shareholders to pay full tax.

Refunds to non taxpayers

Although the particular Australian design arguably was a world first, dividend imputation or something similar is not unusual. Many countries have systems in place that to a greater or lesser degree ensure company profits are taxed only once – among them Canada, New Zealand, Chile, Mexico, Malaysia and Singapore, whose system is called “one-tier” tax.

Many that did adopt it later moved away from it, using the money saved to cut headline tax rates; among them Britain, Ireland Germany and France.

What is unusual is what Australia did next. In 2001 after more than a decade of dividend imputation, the Howard government supercharged it, paying out franking credits in cash to shareholders who didn’t have any or enough tax to offset.

From the point of the view of these non-taxpayers, dividend imputation became a negative income tax: instead of them paying the government money, the government paid them money.

As far as is known, it is an enhancement that has not been copied anywhere.

On one hand, it makes sense because it treats non-taxpayers the same as taxpayers by refunding them the same amount of company tax.

On the other hand, it does not make sense because it means that instead of being taxed once (at either the company or the personal level) as was the original intention, company profits can escape tax altogether.

Untaxed super

From 2007 the change mattered to many more retirees.

The Howard government’s “Simplified Superannuation” package made super benefits paid from a taxed source (that’s most super benefits outside of the public service) tax free when paid to people aged 60 and over.

A quirk in the wording of the Act went further. Not only did super withdrawals become tax free, they also became no longer included in “taxable income” and so didn’t need to be declared on tax forms.

This meant that many retirees on reasonable super incomes were no longer taxed at reasonable rates on their other income, including income from shares which could be untaxed if it fell below the tax free threshold.

And because of the 2001 decision to send dividend imputation cheques to shareholders who were untaxed, these retirees who suddenly found themselves untaxed also got imputation cheques mailed to them from the government.

Self-managed super funds, whose income is tax exempt in the retirement phase, also got imputation cheques.

In July 2017 the Turnbull government wound back tax free super by placing a limiting it to accounts with less than A$1.6 million. The restriction was to hit 1% of super-fund members.

Labor’s proposal

Treasury’s 2015 tax discussion paper prepared for the Abbott government referred to “revenue concerns” about dividend imputation cheques.

They cost the budget just A$550 million in the year the Howard government introduced them, but A$5 billion per year by 2018 and were on track to cost A$8 billion.

Labor’s proposal, announced in mid March 2018, was to return the divided imputation system to where it had been before Howard changed it in 2001, and to where it still is elsewhere. Tax credits could be used to eliminate a tax payment but not to turn it negative.

Labor allowed exceptions for tax exempt bodies such as charities and universities who would continue to receive imputation cheques alongside dividends.

Pensioner guarantee

Two weeks later, in late March, Labor amended its policy by adding a “pensioner guarantee”. Pension and allowance recipients, even part pensioners, would be exempt from the changes and would continue to receive cash payments.

Also exempt would be self-managed super funds with at least one member who was receiving a pension or part-pension at the date of Labor’s announcement, 28 March 2018.

The change cost relatively little (the budget saving over the next four years fell to A$10.7 billion from A$11.4 billion) because most of the imputation cheques go to Australians with too much wealth to get even a part pension.

Self Managed Super Funds

Retail and industry super funds pool their members contributions, and so almost always have tax to reduce, meaning most are would be unaffected by the withdrawal of cash credits.

Self Managed funds usually represent just one person, or a couple; their funds aren’t pooled with anyone else’s. This means that in the retirement phase, where fund earnings are untaxed, most do to have enough tax to reduce. So they get imputation cheques, which they would no longer get when Labor’s policy was implemented.

The Parliamentary Budget Office expects some self-managed funds to change their investment mix and some owners of self-managed funds to transfer their investments to retail or industry funds.

Retirement tax

There is no such thing. The phrase is shorthand for Labor’s proposal to withdraw dividend imputation cheques from dividend recipients who are outside the tax system.

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University