The Queensland Dragon Heath is like a creature in the mist

- Written by Fanie Venter, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, James Cook University

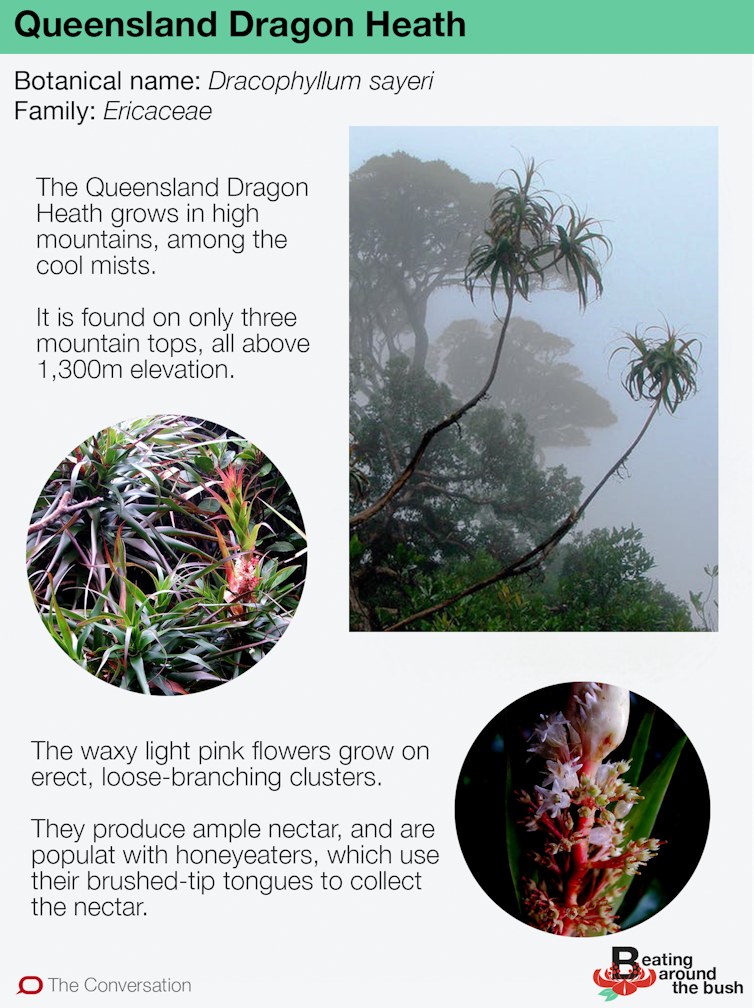

The Queensland Dragon Heath, or Dracophyllum sayeri, is a small, open-branched tree that grows up to 8 metres tall. It also looks decidedly as if someone has stuck pineapple plants or bromeliads on to the tips of its branches.

It has very specific habitat requirements, and is restricted to mountaintops where it receives high rainfall and misty conditions for at least 30 days of the year. The curved and pendulous leaves move in the slightest breeze, looking like they are dancing.

Read more: Queensland's new land clearing bill will help turn the tide, despite its flaws

Walking towards Queensland Dragon Heath plants in the mist evokes a prehistoric feeling. I’m always subconsciously looking out and listening for approaching dinosaurs. One would think that the Dragon Heath plants, with their strap-shaped leaves, would be easy to spot in the vegetation. Not really: it is part of their camouflage on par with the stripes of tigers. When you are further than about 20 metres from a tiger in the bush, it melts into the vegetation.

For this reason, it is easier to spot the stems, with their flaky bark, than the bromelioid leaves of the Dragon Heath. It is of course another story searching for Dragon heaths in New Zealand. In the land of the long white cloud, Dragon Heath species vary from flat cushions, a mere centimetre high, to trees 18m tall, reminiscent of their Queensland counterpart.

It’s rather fun doing fieldwork there looking, at Dragon Heath in the hot sun at the foot of the mountains, then a few hours later trying to take notes with teeth chattering in blizzard conditions. Studying the New Zealand Dragon Heaths is definitely not for the faint-hearted.

Queensland Dragon Heath.

The Conversation

Queensland Dragon Heath.

The Conversation

The Queensland Dragon Heath belongs to the Ericaceae, a large family of 126 genera and about 4,260 species that grow everywhere from icy tundra to steamy tropical rainforests. Ericaceae includes heathers, rhododendrons, azaleas, and blueberries.

The Dragon Heath genus was first described by French biologist Jacques-Julien Houtou de Labillardière, based on a plant he collected in New Caledonia in April 1793. The leaves and stature of the plant reminded him of the dragon trees (Dracaena draco) of the Canary Islands; hence the name Dracophyllum. He described this plant in a book about his travels, aptly named Relation du voyage a la recherche de la Perouse, published in 1800.

Canary Islands dragon tree, inspiration for the Dragon Heath’s name.

Frank Vincentz/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Canary Islands dragon tree, inspiration for the Dragon Heath’s name.

Frank Vincentz/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Dragon Heaths grow across Australia, on the sub-Antarctic islands of New Zealand and New Caledonia. In Australia, they grow from Tasmania in the south to the tropical forests of Far North Queensland, as well as on Lord Howe Island.

Dragon Heaths vary widely, from tiny cushion plants 10mm tall (such as the cushion inka, Dracophyllum muscoides) to a much-branched tree 18m tall (the mountain neinei, D. traversii). The first DNA studies done on the genus Dracophyllum showed that they originated in Australia with two subsequent dispersals at least 16.5 million years ago, one to New Zealand and the other to New Caledonia.

The seeds of Dracophyllum are extremely light, similar to the dust-like seeds of orchids. They can travel very long distances by wind, making it easy to disperse to far-off places, especially during cyclones.

D sayeri flowers Bellenden Ker.

Photo: Fanie Venter

D sayeri flowers Bellenden Ker.

Photo: Fanie Venter

But the Queensland Dragon Heath is far more localised than its cousins. It is only known to grow on three mountaintops in Queensland (Mt Bellenden-Ker, Mt Bartle Frere, and the eastern slopes of Mt Spurgeon), all above 1,300m elevation. The species name D. sayeri is after the naturalist W.A. Sayer, who collected the type specimen in 1886 on Mt Bellenden-Ker, the second highest peak in Queensland.

It prefers to grow in fairly open low rainforest on mountain ridges where there is lots of air movement, and it can grow in thin layers of humus-rich granitic soils. Temperatures on the mountain peaks are normally low, with a maximum of 25℃ during the day and a minimum of 15℃ in the evenings.

A unique feature is the strap-shaped leaves that are parallel-veined, a character normally associated with monocots (lilies, grasses, sedges, and so on) rather than with dicots (plants with net-like veins).

The waxy light pink flowers are arranged in erect, loose-branching clusters. They produce ample nectar, which is popular with our feathered friends, the honeyeaters, which use their brushed-tip tongues to collect it.

Read more: Bunya pines are ancient, delicious and possibly deadly

Unfortunately the Queensland Dragon Heath is difficult to grow. It is really a plant for gardens in cooler climates and the chances of growing this plant is enhanced if the soil is inoculated with micorrhiza (fungal strands that exchange nutrients between their surroundings and their host plant) and the soil is kept moist. A thick layer of leaf mulch will keep the fine roots moist and cool.

I have succeeded in growing most of the New Zealand Dracophyllum species but had limited success with the alpine species. My next challenge is to grow the Queensland Dragon Heath successfully so that we can introduce this ancient-looking gem into horticulture.

Authors: Fanie Venter, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, James Cook University

Read more http://theconversation.com/the-queensland-dragon-heath-is-like-a-creature-in-the-mist-109644