how the Soviet film redrew the boundaries of cinema

- Written by Alexander Howard, Senior Lecturer, Discipline of English and Writing, University of Sydney

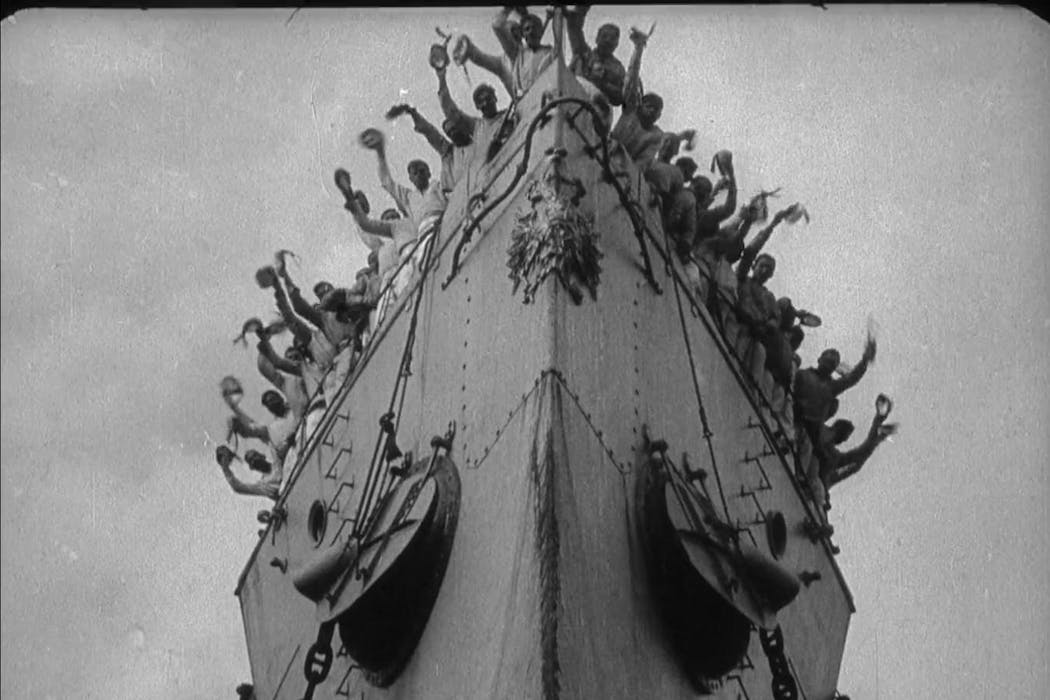

People crowd together in the sun. All smiles and waves. Joyous.

Pandemonium erupts. Panic hits like a shockwave as those assembled swivel and bolt, spilling down a seemingly infinite flight of steps.

Armed men appear at the crest, advancing with mechanical precision. We are pulled into the chaos, carried with the writhing mass as it surges downward. Images sear themselves on the retina. A child crushed underfoot. A mother cut down mid-stride.

An infant’s steel-framed pram rattling free, gathering speed as it hurtles downward. A woman’s glasses splinter, skewing across her bloodied face as her mouth stretches open in a soundless scream.

I’ve just described one of the most famous sequences in the history of film: the massacre of unarmed civilians on the steps of Odessa. Instantly recognisable and endlessly quoted, it is the centrepiece of Sergei Eisenstein’s masterpiece, Battleship Potemkin, which turns 100 this month.

A new front for cinema

Battleship Potemkin redrew the boundaries of cinema, both aesthetically and politically.

It is a dramatised retelling of a 1905 mutiny in the Black Sea Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy – a key cresting point in the wave of profound social and political unrest that swept across the empire that year.

The first Russian revolution saw workers, peasants and soldiers rise up against their masters, driven by deep frustration with poverty, autocracy and military defeat.

Although the tsar remained in power, the discord forced him to concede limited reforms that fell far short of what had demanded.

The impetus for the historical mutiny on the Potemkin was a protest over rotten food rations. Eisenstein emphasises this in his film, lingering on stomach-churning close-ups of maggots crawling over spoiled meat.

When the sailors refuse to eat the putrid rations, they are accused of insubordination and lined up before a firing squad. The men refuse to gun down their comrades and the crew rises up, raising the red flag of international solidarity as they symbolically nail their colours to the mast.

A sailor called Vakulinchuk, who helped lead the uprising, is killed in the struggle. Sailing to Odessa, the crew lays his body out for public mourning and the mood in the city becomes increasingly volatile. Support for the sailors swells, and the authorities respond with lethal force, sending in troops and prompting the slaughter on the Odessa Steps.

The Potemkin fires on the city’s opera house in retaliation, where military leaders have gathered. Soon after, a squadron of loyal warships approaches to crush the revolt. The mutineers brace for battle, but the sailors on the other boats choose not to fire. They cheer the rebels and allow the Potemkin to pass in an act of comradeship.

At this point Eisenstein departs from the historical record: in reality, the 1905 mutiny was thwarted and the revolution suppressed.

Political myth-making

Battleship Potemkin was commissioned by the Soviet State to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the revolution.

The new Bolshevik administration viewed cinema as a powerful tool for shaping public consciousness and Eisenstein – then in his late 20s and gaining attention for his radical theatre work – was tasked with creating a film that would celebrate the origins of Soviet power.

Eisenstein initially planned a sprawling multi-part film canvasing the revolution’s major events, but faced production constraints. He turned instead to the Potemkin, a story which allowed him to depict oppression, collective struggle and the forging of revolutionary unity in a distilled form.

The finished piece was less a literal history lesson than a highly stylised piece of political myth-making.

When Potemkin was presented at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre in December 1925 the invited spectators, a mix of communist dignitaries and veterans of the abortive 1905 mutiny, punctuated the screening with bursts of wild applause – none more ecstatic than when the battleship’s crew unfurl the red flag, hand-tinted a vivid red on the black and white film.

Celebrated – and banned

Battleship Potemkin was a global sensation. Filmmakers and critics hailed it as truly groundbreaking. Charlie Chaplin declared it “the best film in the world”.

Yet its impact also made it feared. Governments recognised the volatile political charge running through its images. In Germany it was heavily cut, and in Britain it was banned. Even so, prints continued to circulate, and the film’s reputation only grew.

Eisenstein’s growing international status did little to protect him at home. As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s, the tides of Stalinist cultural policy began to turn sharply against him. Eisenstein’s approach was profoundly out of step with the new aesthetic of Socialist Realism, which demanded clear narratives, heroic characters and unambiguous political messaging.

Where his signature technique, montage, was dynamic and dialectical, Socialist Realism insisted on straightforward storytelling and easily digestible moral lessons. As a result, Eisenstein found himself accused of obscurity, excess and political unreliability.

Several of his projects were halted; others were taken out of his hands altogether. Those he did complete were admired, but none matched the impact of Battleship Potemkin.

A century on, its vision of oppression, courage and collective resistance still crackles with an energy that reminds us why cinema matters.

Authors: Alexander Howard, Senior Lecturer, Discipline of English and Writing, University of Sydney