Vanessa was ‘kidnapped’ by the family policing system aged 10. Now, she’s fighting for other First Nations families

- Written by Allanah Hunt, Lecturer, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, The University of Queensland

“When you take a child, you are taking sovereignty, their role, their connection – you are taking whole communities that live inside that little being,” writes Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts.

Her memoir, Long Yarn Short, imprinted on my mind and heart. In a warm, inviting voice, this proud Bundjalung Widubul-Wiabul woman paints an unflinchingly honest picture of her life as a child stolen by the state, at just ten years old, in the mid-2000s. She describes being “tucked up in bed” by her dad and “about to close [her] eyes” when it happened.

“I want you to imagine your dad going out onto the balcony, terrified,” she writes. “I want you to hear him yelling, ‘Bub … Big girl. I am so sorry, but they are coming to get you’.”

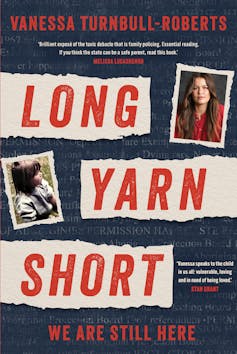

Review: Long Yarn Short by Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts (UQP)

Turnbull-Roberts spent eight years in various out-of-home care placements (foster care) in Sydney. Through this time, she fought to see her family whenever she could, but it was mostly on restricted monthly supervised visits. With great resilience, she refused to allow the state to steal her identity and connection. At 18, when she aged out of the care system, she returned to Bundjalung Country for the first time. On her return, she completed a law degree at University of New South Wales, with the help of a scholarship that allowed her to stay in student housing.

Now, in her role as the Australian Capital Territory’s Commissioner for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Young People, the human rights lawyer and Fulbright scholar fights for other First Nations children to not face the same trauma she did. She wants to prevent them from being “crossover children”, going from the foster care system to juvenile detention.

Kidnappers, not case workers

Turnbull-Roberts was “born to two parents who were battling their own demons”, but describes the feeling of love and care that was always there.

Her mother had schizophrenia, which she was demonised for in the health and foster care systems – where, Turnbull-Roberts writes, she also experienced abuse related to her mental health. Her father was a Bundjalung man carrying generational trauma, who had some unhealthy coping mechanisms – something he was punished for, never helped with.

Turnbull-Roberts and her brother moved between the houses of her parents, who “co-parented in a more open, flexible way than could be understood by Western ways of parenting” at the time she was stolen. Her older brother was with her mother the night she was taken – and he remained with her.

“There was no reason why Mum could not take me,” Turnbull-Roberts writes. Her mother’s mental illness had been “used against her to justify the removal” of the first of her three children, Turnbull-Roberts’ eldest brother. Since Turnbull-Roberts was conceived, her mother had feared her being taken as well. “In my world, she was my mum, my everything,” Turnbull-Roberts writes.

She chooses her words carefully and poignantly, never buying into the euphemisms and lies of a system built to destroy her connection to kin and culture. They aren’t “case workers”, they are “kidnappers”. They aren’t “removing” her, they are “kidnapping”.

As I read, Turnbull-Roberts never let me forget she was ripped away from community, family and warmth, to be neglected and abused by a system that proclaimed it saved her from neglect and abuse.

‘A familiar lie’

In a note to her younger self at the end of the book, Turnbull-Roberts writes that she has “embarked on journeys in law and social work, dedicating herself to supporting other youth and children, fighting for her people”.

This story, perpetuated by the family policing system, of Indigenous children being neglected and unloved by their parents, is a familiar lie. These were the exact narratives spun when justifying historic oppressive policies, like the original Stolen Generations.