First-ever biomechanics study of Indigenous weapons shows what made them so deadly

- Written by Michelle Langley, Associate Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University

For the first time, state-of-the-art biomechanics technology has allowed us to scientifically measure just how deadly are two iconic Aboriginal weapons.

In First Weapons, an ABC TV series aired last year, host Phil Breslin tested out a range of Indigenous Australian weapons. Amongst these were two striking weapons – the paired leangle and parrying shield, and the kodj.

Both weapons are used to strike at an opponent. While the warriors who wield them are well aware of the weapons’ lethality, our team was approached by the show’s creators, Blackfella Films, to use modern biomechanic tools and methods to assess them.

Our goal was to determine exactly where their striking power comes from and just what makes their ancient designs so deadly. Our study is now published in Scientific Reports.

Deadly weapons

We studied the kodj made by Nyoongar peoples of the southwest of the Australian continent and the leangle and parrying shield from the southeast.

The kodj is part hammer, part axe, and part poker. Its design is likely tens of thousands of years old, though determining exactly when this tool form was invented is difficult – only the stone parts can survive the archaeological record long term.

So far, the oldest axe recovered from an Australian archaeological site dates to between 49,000 and 44,000 years ago. It was found in a Bunuba site called Carpenter’s Gap 1.

What is a kodj? (First Weapons, Blackfella Films, ABC).The beauty of this weapon is its ability to be “pivoted by a turn of the wrist so that the blade can cut in any direction”.

The kodj used in our experiment was made by Larry Blight, a Menang Noongar man from Western Australia. Its handle is carved from wattle wood with a sharpened boya (stone) blade attached to one side and a blunt boya edge on the other with balga (Xanthorrhoea or grass tree) resin.

The leangle and parrying shield we studied were made by expert weapon-makers Brendan Kennedy and Trevor Kirby on Wadi Wadi Country. Each was carved from hardwood and are traditionally used together in one-on-one, close quarters combat.

Weapon-makers Brendan Kennedy and Trevor Kirby making the leangle and parrying shield used in this experiment (First Weapons, Blackfella Films, ABC).Determining when this weapon was invented is even more difficult than the kodj, because both the leangle and its paired shield are entirely made of wood. Wood rarely survives long term, and certainly not over the thousands of years needed to track its innovation.

Currently, the oldest surviving wooden artefacts found on the Australian continent are 25 tools including boomerangs and digging sticks recovered from Wyrie Swamp, South Australia. They are more than 10,000 years old and only preserved because they were in a waterlogged environment which protected them from decay.

See the leangle and parrying shield in action on Wadi Wadi Country (First Weapons, Blackfella Films, ABC).Biomechanics of the weapons

There are no previous studies describing human and weapon efficiency when striking with a hand-held weapon, so we were starting from scratch. For this study, the show’s host, Phil Breslin, acted as the warrior putting the weapons through their paces.

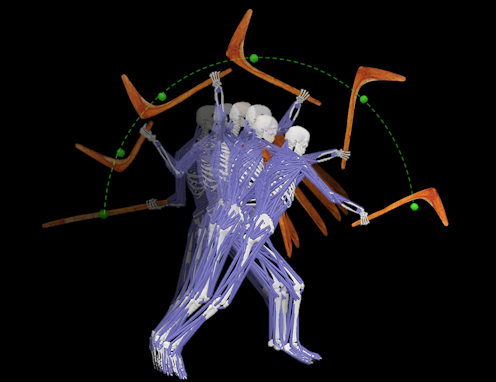

Using wearable instruments, we tracked the human and weapon kinetic energy and velocities built up during kodj and leangle strikes. Biomechanical analyses provided insights into shoulder, elbow and wrist motions, and the powers reached during each strike motion.

These tests found that the leangle is far more effective at delivering devastating blows to the human body than the kodj.

The kodj, on the other hand, is more efficient for an individual to manoeuvre, but still capable of delivering severe blows that can cause death.

Over the past few hundred years, European writers have noted a range of weapons have been used in conflict both within and between First Nations on the Australian continent. Stencils and painting of these same weapons appear in rock art, recording their presence prior to European arrival.

Some weapons were also used in dispute resolution. These included “trial by ordeal”, whereby an accused person must face a barrage of projectiles (spears or fighting boomerangs) unarmed or with a shield. Such trials often resulted in injuries, but rarely in death.

Archaeological evidence for interpersonal violence (injuries of skeletal remains) is rare in Australia, but when found, usually consists of depressions to the skull and “parrying fractures”. These are breaks to the arm bones above the wrist, resulting from the raising of the arm in defence against a weapon. This can be either from a direct blow or a glancing blow off a shield – like the one used in this experiment.

Cultures around the globe have invested significant time and effort into designing deadly hand-held weaponry. Our results show that while design is critical for weapon efficiency, it is the person who must deliver the deadly strike.

Authors: Michelle Langley, Associate Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University