Stirring films made the Snowy scheme a nationbuilding project. Could the troubled Snowy 2.0 do the same?

- Written by Belinda Smaill, Professor of Film and Screen Studies, Monash University

In 2017, then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull alighted from a helicopter to announce a grand plan: Snowy Hydro 2.0. It would turn the famous hydroelectric scheme into a giant battery, ready to power the green transition.

Turnbull no doubt expected his announcement would associate his leadership with the positive aura of the enormous post-war Snowy scheme, since mythologised as the foremost nation-building achievement of the 20th century.

But bad press has plagued Snowy 2.0. Recent news of a tunnel collapse is the latest episode in ongoing mechanical problems. There have been reports of environmental mismanagement, bogged tunnelling machines and cost blowouts. The constant stream of bad stories have outweighed any nation-building glow.

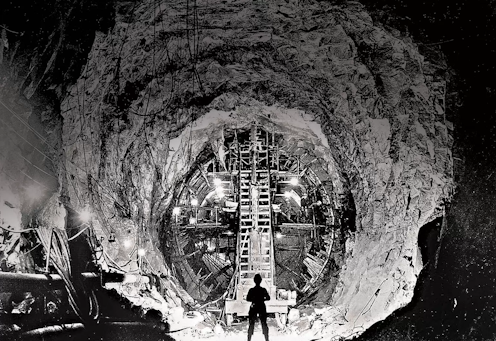

Or has it? Snowy 1.0 took 25 years to complete. It was a huge task to divert the Snowy River inland through tunnels, bolstering water supplies in the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers and generating power through hydroelectricity. Workers died. Costs blew out. But the mythology of the project grew, partly driven by promotional films depicting the project as a source of national pride and power.

A tale of two projects

Snowy 2.0 is overseen by a government-owned corporation, Snowy Hydro. Its public relations program includes social media, an onsite Discovery Centre and a YouTube channel with monthly video updates narrated by Snowy 2.0 personnel.

To date, the biggest boon for the project has been the three-part SBS series, Building the Snowy, first broadcast in August 2023. While not formally a product of Snowy Hydro, the series has an upbeat tone. Extensive use of archival footage strongly links current works to the celebrated post-war scheme.

Despite these efforts, Snowy 2.0 is now nationally known for slow progress and cost blowouts. The negative perception is fair. Snowy Hydro bosses admit there have been unanticipated setbacks.

Is it too late to change these perceptions? Not necessarily. Energy projects can be powerfully reimagined and legitimated in the public sphere. The original Snowy Scheme of the 1950s offers a formidable template.

This wasn’t by accident. Sir William Hudson, an engineer tasked with managing the Snowy scheme, had witnessed the successful promotion of Roosevelt’s 1930s New Deal policies in the United States, including the construction of the monumental Hoover Dam.

Hudson decided to follow suit, investing heavily in promotion. This, it turned out, was wise. The scheme’s early years were fraught. Political wrangling meant the scheme was started under Commonwealth defence powers until it was formalised by state legislation in Victoria and NSW in 1959. It could easily have been cancelled or curtailed.

As the building progressed, workers began to die in accidents – a tally which would reach 121. States continued to disagree about the allocation of water for irrigation.

Hudson had to convince both the public and politicians of its merits. In addition to the usual press releases and newsreels, Hudson turned the works into a tourist attraction, taking people into the mountains by the busload.

Documentaries by the dozen

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Snowy Mountain Authority sponsored a prolific photographic section, which put out huge volumes of photos – and around 130 documentaries.

Some of these weren’t aimed at a wide audience, such as safety training films or recruitment films to sustain the workforce.

But there were dozens which deliberately set out to create a favourable image of the scheme. The experienced cinematographer Harry Malcolm produced many of these films, which were shown at film festivals, schools and community group screenings.

The films made much of the spectacular alpine environment. Some showed the lives and accommodation of workers and their families in company towns such as Khancoban and Cabramurra. Only a few mentioned the multicultural workforce the scheme is known for.

Titles include Where Men and Mountains Meet (1963), Challenge of the Great Divide (1967) and Where the Hills Are Twice as Steep (1958). This last features a male narrator speaking from the perspective of Mt Kosciuszko, describing a chronology from deep time to colonisation to the problems of irrigation and electricity the scheme was meant to solve.

A high point was Conquest of the Rivers (1957), which won awards at film festivals and circulating internationally.

The semi-fictionalised documentary tells the story of Tom Carpenter who leaves his drought-affected home west of the Great Dividing Range with his small family and travels to Cooma to work on the Snowy.

Conquest of the Rivers emphasises a better future, created by the labour of male bodies as they carve paths inside mountains. The film draws on wartime tropes of capable masculinity.

Taken together, these documentaries offered a stabilising discourse for the nation against the massive social change brought by the large Baby Boomer generation.

By 1960, the films had done their work. There was widespread enthusiasm for the project and its future was guaranteed.

There’s a telling quote from Tom Mitchell, a critic of the scheme, in Margaret Unger’s Voices from the Snowy:

In 1960 Upper Murray people suffered from a strange disease known as ‘Snowyitis’ which consisted of an overwhelming enthusiasm for the Snowy Scheme, almost rising to the fervour of a Billy Graham crusade. And yet, if asked, no one could really define the benefits

These films were never meant to be even-handed. Instead, Harry Malcolm’s films were a potent mix of truth and illusion, distracting from real problems such as deficient safety standards, low worker morale, and alarmingly, no planning for floods until after devastating floods on the Murray in 1956.

Could history repeat?

Just like the original Snowy scheme, the future of Snowy 2.0 is not assured. Its original backer has left politics. Enormous engineering challenges have yet to be overcome.

Could Snowy 2.0 be reframed as 1.0 did? It is possible. But it would require a much more imaginative storytelling regime, beyond photos of large tunnelling machines or commentary from engineers.

To make it successful in the public eye, it should harness the new story of our time – the essential energy transition away from fossil fuels and the creation of a new grid. It should connect this project in the mountains to the needs of people around the nation, appealing to the senses and conjuring up the desired future.

And it cannot be only in the realm of PR – Snowy 2.0 must make our environmental plight better, not worse.

Authors: Belinda Smaill, Professor of Film and Screen Studies, Monash University