the sublime kith and kin is simultaneously somber and stirring

- Written by Wes Hill, Associate Professor, art history and visual culture, Southern Cross University

This article mentions ongoing colonial violence towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The names of the dead resound in Archie Moore’s sublime, Golden Lion winning installation at this year’s Venice Biennale. Moore is the first Australian to win the prestigious award, given to the best national pavilion at the world’s oldest and most renowned art biennale, which began in 1895.

Singled out from 85 other national presentations, Moore’s kith and kin is exceptional in many ways. Intelligently supported by curator Ellie Buttrose, Moore has given the black cubical modernist Australian pavilion an internal form that perfectly complements its outer appearance.

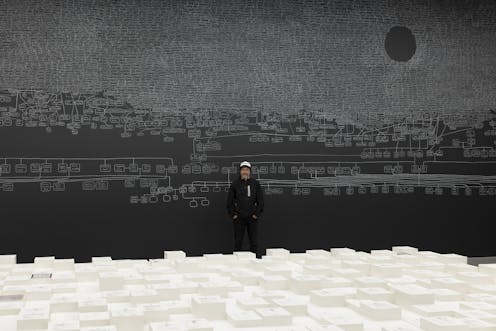

Having long been attracted to the gothic, an enormous, hand-drawn family tree by Moore greets viewers with its powerful, eulogistic presence.

Rendered with white chalk on black chalkboard-painted walls, Moore’s ancestral connections – real and imagined – branch out onto the ceiling. The dimly lit gallery becomes a church, a cave and a classroom. When entering on a spring Venetian day, the walls shimmer. At a distance, they evoke the late great Nyapanyapa Yunupingu, an Australian Yolngu painter renowned for her ghostly white paintings.

On a large plinth in the centre of the space, a memorial-like display of precisely amassed papers of varying heights is enclosed by a shallow pool of water.

Rows of redacted material from coronial inquests into the 557 Aboriginal people who have died in police and prison custody since 1991 provide a solemn, micropolitical base to Moore’s work.

It conjures all the bureaucratic processes dealing with Aboriginal injustice that have been announced, shelved or failed, and the chains of lives affected. It’s a centrepiece that wouldn’t be amiss in the oeuvre of Hans Haacke. From the late 1960s, the work of the German-American conceptualist has prefigured much of today’s issue-driven art.

Read more: Why we should honour the humanity of every person who dies in custody

Triumphant and cinematic

Given the soberness of its central object, it is all the more remarkable that kith and kin manages to still be triumphant and, in its atmospheric slowing down of time, vaguely cinematic. The work is essentially a hybrid of two series Moore has shown before – Family Tree (2018) and Inert State (2023) – dramatically upping their scale.

Together, both pieces transmute macro and micro histories into a stirring, labour-of-love installation. In following his parental lineages, two ways of representing ancestry – Aboriginal and European – converge, just as the two series of works – one based in drawing, the other in sculpture – are made to share the space with one another.

Like all family trees, kith and kin begins with the self-consciousness of the person doing all the research. Moore is a descendant of Bigambul and Kamilaroi people on his mother’s side and Scottish and British people on his father’s. “Me” appears in the middle of the back wall. It connects to the names “Stanley Moore” and “Jennifer Cleven”: the artist’s parents.

Moore racked up hundreds of hours (and identified more than 3,000 relatives) on the popular website Ancestry.com. In his archival research, he also discovered a genealogical chart made by anthropologist Norman Tindale, who interviewed Moore’s maternal great-grandmother in 1938.

Moore extrapolates the genealogical underpinnings of identity-based art literally, into a chart that, as he says, spans 2,400 generations and 65,000 years. Arriving in Venice early, he spent over two months drawing this inventory of thousands of names on the wall, in what must have been a melancholic yet spiritual endeavour.

Each name is surrounded by an imperfectly drawn box interconnected with lines to other boxes. Some boxes are left empty, signifying, in a reversal of logic, relatives who are still alive.

Higher up on the wall, the dead on his mother’s side are overwhelmingly represented by singular and diminutive names such as “Tommy”, “half-caste”, “old gin” and “abo”. Moore does not discount their presence due to their neglect by history’s gatekeepers. Instead, he gives them the dignity of at least occupying a space in his part-arboreal, part-rhizomatic system.

Generations marked by anonymous and racist epithets are turned by Moore into beatific survivalist motifs. Sensitive to the ghosts of the past, the work addresses the failures of colonialist and continuing regimes in Australia, the racist appellations and redacted names reminders of a desire to have some people lost to history.

Presenting for, not representing, Australia

In following an archival impulse, Moore often undertakes extensive historical research only to concentrate on the absences and inconsistencies he finds there. It’s an approach that corresponds with Hal Foster’s observation of a tendency amongst cognisant artists in the digital age who “make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present”.

This dichotomous treatment of archives – turning their specificity into speculative projections – may be what sets Moore, who has long been regarded as an “artist’s artist”, apart from many of his Indigenous peers. He is a particularly brilliant but often underappreciated interpreter of historical material.

Conscious of how forms are engaged with and read in specific contexts, he always seems to make more of his messaging than what is actually there.

Capturing the zeitgeist of the Venice Biennale’s pronounced First Nations-led approach this year, kith and kin mixes politics and history with the poetry of internalised anxieties around belonging. Adamant that he was “presenting for” rather than “representing” Australia, Moore’s paean to a “larger network of relatedness” has nonetheless done us all proud.

Read more: We're analysing DNA from ancient and modern humans to create a 'family tree of everyone'

Authors: Wes Hill, Associate Professor, art history and visual culture, Southern Cross University