why thousands of Rohingya are desperately trying to escape refugee camps by boats

- Written by Ruth Wells, Senior research fellow, Psychiatry and Mental Health, UNSW Sydney

Late last week, a boat crammed with Rohingya refugees fleeing a squalid camp in Bangladesh capsized off the coast of Indonesia. Around 75 people were rescued, including nine children, but more than 70 are missing and presumed dead.

This tragedy isn’t an isolated incident. The number of Rohingya people trying to escape refugee camps by boat has skyrocketed in recent months.

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 1,783 Rohingya refugees boarded boats from Bangladesh from January to October 1, 2023. Since then, around 3,100 people have embarked on these treacherous journeys – an increase of nearly 74%.

Since January 2023, around 490 Rohingya have been reported dead or missing, including 280 since October 1.

Their attempts to reach countries like Malaysia and most recently Indonesia are being met with refusals and pushbacks, leaving many Rohingya stranded at sea and vulnerable to exploitation, trafficking and even death.

Why are so many Rohingya trying to flee in recent months? And how should the international community respond to this increasingly desperate humanitarian crisis?

In a new article recently submitted for peer review, we (two Australian academics and six anonymous Rohingya activists) describe the “push factors” that have been identified in community-based research in the camps, which are forcing many people to board boats to try to reach safety.

Living with constant tension

The nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees now living in Bangladesh are survivors of a massive Myanmar military operation in 2017 aimed at driving them from their homes in western Rakhine state.

Estimates of the number of people killed during the operation range from around 7,800 to 24,000. The United Nations has called it a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” and genocide.

Even before they were forced across the border, the Rohingya people had been subjected to decades of discrimination, denial of citizenship, exclusion from schools and work, restrictions on freedom of movement and violence from authorities.

Now, trapped in limbo in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, they are experiencing many of the same things.

In 2019, we conducted on-the-ground interviews with 27 Rohingya community experts living in Cox’s Bazaar, including teachers, mothers, religious leaders, spiritual healers, youths and activists. We wanted to know how Rohingya people understand and describe the psychological impacts of genocide and displacement.

This understanding is important because most mental health services are based on Western terminology like “depression”, “anxiety” or “stress”. But these may not properly fit the Rohingya experience. Instead, we found the English word “tension” (in Rohingya, sinta) was used by many refugees, which conveys feelings of worry, concern and anxiety and captures the experience of being stateless.

As two anonymous adolescent Rohingya women described it to us:

There is no opportunity to do anything, all we do is stay inside.

Tension is loss. We’ve lost land, children, husband, that’s why we feel tension.

Tension is neck pain. Tension is throat, shoulders and head pain.

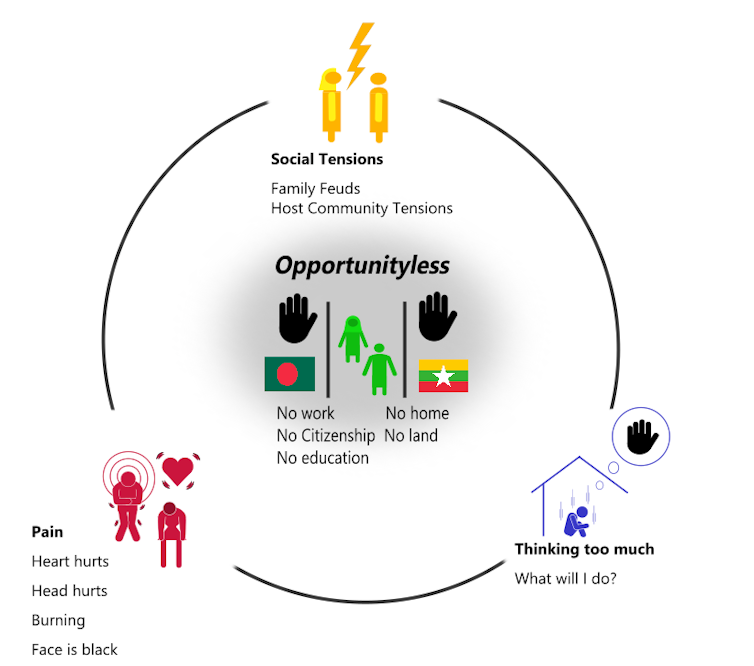

After conducting our interviews, we then developed a pictorial model of “tension”, as Rohingya is an oral language. The model (below) showed how being “opportunity-less” – from lack of work, education or freedom of movement – sits at the centre of tension.

Our interview subjects told us lack of opportunity leads to thinking too much, pain in the body and conflict in the family, between families and with the Bangladeshi community.

What Australia and regional partners should do

What can – and should – the international community do to find a durable solution to this problem?

As a well-resourced regional partner, Australia can play a much bigger humanitarian role not focused solely on punishing people smugglers or the refugees themselves through boat turnbacks.

When people are faced with such dire conditions, they will move, no matter the cost. As recent refugee boat arrivals in Australia and Indonesia demonstrate, boat turnbacks and arrests fail to address the root causes of forced migration. They do not “stop the boats”.

Here are our recommendations for what Australia, New Zealand and their regional partners should do instead to help the Rohingya people:

1. Exert diplomatic pressure on the Myanmar junta to recognise Rohingya citizenship and facilitate a peaceful resolution to the ongoing conflict in Rakhine state so the refugees can return home.

2. Address the shortfall in funding to humanitarian organisations working in Bangladesh to address the immediate needs of Rohingya refugees, including food, shelter, health care, proper education and psychosocial support. Invest in the resilience of refugees.

3. Increase pressure on Bangladesh to improve conditions in the refugee camps and provide livelihood opportunities for Rohingya refugees. This includes advocating for policies that allow refugees to work legally and contribute to the local economy.

4. Prioritise resettlement opportunities for Rohingya refugees in third countries, especially those who have been displaced since the 1990s. Resettlement offers a durable solution for those in need of international protection, providing them with the opportunity to rebuild their lives in safety and with dignity.

Authors: Ruth Wells, Senior research fellow, Psychiatry and Mental Health, UNSW Sydney