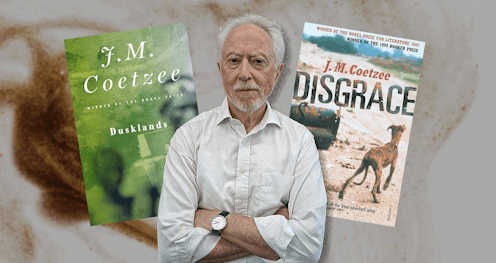

J.M. Coetzee’s provocative first book turns 50 this year – and his most controversial turns 25

- Written by Andrew van der Vlies, Professor, School of Humanities, University of Adelaide

J.M. Coetzee, one of the leading novelists of our age, turns 84 this year. Last year, he published The Pole and Other Stories, his 18th book (excluding volumes of criticism, commentary, letters and translations). Its flowering of mature style confirms that this writer remains at the top of his game.

Coetzee celebrates another milestone this year: 50 years of publishing serious, provocative fiction. His work is always formally daring, brave in its social critique and its refusal to play by the rules.

Dusklands

Coetzee’s first book, Dusklands, appeared in April 1974. It was published by a small press in Johannesburg called Ravan, which had built a modest reputation for oppositional writing under apartheid. Coetzee’s debut was a slim volume with an unassuming – even deliberately dull – cover that belied the incendiary force of the two stories it contained.

Its first part, The Vietnam Project, is set in the United States during the early 1970s. Its narrator, Eugene Dawn, meditates on his work as propaganda-warfare analyst for the US military’s operations in Vietnam.

“I have an exploring temperament,” he declares. “Had I lived two hundred years ago I would have had a continent to […] open to colonization.”

Eugene Dawn’s dreams of “total air-war” precipitate his decline. He holes up in a motel with Patrick White’s Voss and Saul Bellow’s Herzog – novels concerned with the decline of overreaching rational minds.

The drive to explore and dominate also compels the protagonist of the book’s second part, The Narrative of Jacobus Coetzee. The story is presented as as a translation, with parodic scholarly apparatus, of a record by a (real) 18th-century explorer. Jacobus Coetzee describes expeditions into the interior of what is now the Western and Northern Cape provinces of South Africa.

“I am a hunter,” he states, “a domesticator of the wilderness, a hero of enumeration.”

He recounts how, in 1760-61, he encounters the indigenous Khoisan people in the hinterlands of the Dutch settlement. He regards them as “completely disposable” and treats them like animals, seeing them as “game”. Their murder by the increasingly unhinged frontiersman is narrated with stomach-turning glee, as Jacobus Coetzee appears to descend into a madness born of megalomania.

“I am a tool in the hands of history,” he declares. “I have other things to think about.”

Each part of this bracing debut, then, offered an implicitly satirical engagement with the excesses of colonial adventuring. The book was formally daring, too. Was this a novel or two novellas, its first readers wondered. How was one to interpret the 18th-century “narrative” that presented itself as a historical document?

The juxtaposition of two widely divergent settings drew attention to what the narratives shared. It connected the narrators’ self-satisfied posturings as missionaries of “civilization” in a bravura indictment of Western Enlightenment discourses.

The boldness and novelty of approach led Jonathan Crewe – the book’s first South African reviewer – to herald of the arrival of the modern novel in the country. Some of the more avant-garde and oppositional Afrikaans writers of the previous decade would no doubt have demurred. But Crewe’s comparison of Dusklands with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness remains apt.

Both books feature the “journey of the Western consciousness out of the polity and into the void,” Crewe wrote. Both cast that journey as critique rather than celebration of Western attitudes.

Read more: How Conrad’s imperial horror story Heart of Darkness resonates with our globalised times

A revolutionary text

Rita Barnard, a South African-born academic at the University of Pennsylvania who has taught Dusklands for many years, has observed that her students increasingly baulk at the book’s violence. They resent that they are being asked to occupy the subject position of the white perpetrator.

Barnard has some sympathy with this response. “After all,” she muses,

revelations about colonial discourse that Dusklands stunned us with in the 1970s are no longer new; my students were already trained to look for silences, racist misrepresentations, and epistemic violence in a text.

Yet Dusklands was undoubtedly revolutionary for its moment. Nelson Mandela was eight years into his life sentence. The Soweto Rising and the death of Steve Biko in police custody had not yet galvanised internal opposition. Overtly anti-apartheid works were routinely repressed. The formal end of apartheid was still 20 years away.

In this context, it is difficult to conceive of a bolder attack on the ideas of apartheid’s ideologues. No other work had dared to link apartheid’s originary narratives (as the explorer accounts undoubtedly are) to Kissinger-era realpolitik.

For all our laudable attention to trigger warnings, we should welcome fiction that unsettles our complacent sense that philosophical opposition to colonial violence and its legacies might be sufficient absolution. Dusklands forces the reader into uncomfortable cohabitation with characters who are implicated in genocide, but convinced of their moral rectitude.

One hardly need elaborate the ongoing lesson this holds for readers in the present.

Disgrace

As arbitrarily neat temporal markers would have it, this year is also a significant anniversary for another of Coetzee’s most provocative works.

Disgrace was published in August 1999, five years into the “new” South Africa, and against the backdrop of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the country’s great experiment in truth-telling. It won Coetzee his second Booker Prize, making him the first author so celebrated.

Set in a recognisable present, Disgrace is Coetzee’s most deceptively straightforward realist narrative. Its university setting, similar to the University of Cape Town, generated all manner of misguided speculations about whether it was a roman à clef.