The 2 main arguments against redesigning the Stage 3 tax cuts are wrong: here’s why

- Written by Steven Hamilton, Visiting Fellow, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

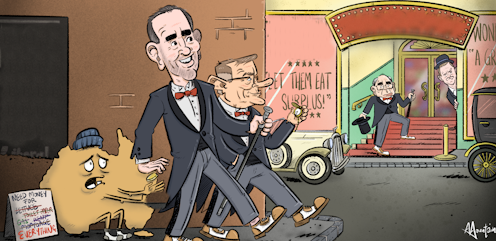

As debate over the Stage 3 tax cuts has raged, I’ve encountered two common defences of the package as it was, before Anthony Albanese rejigged it.

First, that this is merely the third stage of a program of tax cuts, coming after the earlier two stages that went to low and middle earners.

Former treasurer Peter Costello made that argument this week, saying Stage 3 was

part of a package, and stage one and two have already been delivered – one and two were the parts of the tax cuts directed at low and middle-income earners, and this is the final part.

I, too, have made a version of this point in the past. But it turns out to be completely wrong.

To see why it’s wrong, it’s necessary to go back six years to the 2018-19 budget, when Scott Morrison as treasurer and Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister first announced the three stages, and the 2019-20 budget when Scott Morrison as prime minister and Josh Frydenberg as treasurer refined them.

Doing so reveals some crucial facts. The first is that Stage 1, the so-called low- and middle-income tax offset, was to be merely temporary and would disappear once the other stages were in place.

Stage 2, which took place over a number of years, raised the threshold at which the 19% rate kicks in from A$37,000 to $45,000; raised the threshold at which the 37% rate kicks in from $87,000 to $120,000; and increased a separate so-called low-income tax offset from $445 to $700.

Stage 3, the one scheduled for July 1, consisted of: lowering the 32.5% rate to 30%; eliminating the 37% tax bracket entirely; and raising the threshold at which the 45% rate kicks in from $180,000 to $200,000.

Stage 2 wasn’t progressive, stage 1 didn’t last

How should we assess the fairness of the first two stages? Economists describe a tax system as “progressive” if the share of income paid in tax rises with income.

We then describe a change to a tax system as progressive if it delivers a proportionally greater cut to lower-income recipients, increasing the progressivity of the system.

It works the other way for a regressive tax cut. And we call a change that doesn’t alter the progressivity of a tax system “flat”, meaning it gives the same proportion of income in relief to all taxpayers.

In the below figure, I’ve taken the original Stage 2 and Stage 3 together and plotted the total tax cut as a share of each taxable income, and then done the same thing for Stage 2 and Albanese’s rejigged Stage 3 taken together.

The results are revealing.

Below is the same graph, but for Stage 2 only.

It shows that Stage 2 did not, as Costello and others have claimed, go mostly to low and middle earners. Rather, it went to everyone earning more than $37,000 per year as a roughly equal proportion of their income.

In other words, it was roughly flat. It didn’t alter the progressivity of the tax system much at all.

The original Stage 3 was extremely regressive, as can be seen in the first graph. When combined with Stage 2 it gave the biggest benefits as a share of income to Australians earning $200,000. It gave much less as a share of income to Australians earning $87,000 or less.

The main reason it’s so regressive is the elimination of the 37% tax bracket, which by itself delivers a tax cut of more than $4,000 a year to every person earning more than $180,000 per year.

Read more: Albanese tax plan will give average earner $1500 tax cut – more than double Morrison's Stage 3

As it happens, the Albanese government’s redesigned package, while not regressive, isn’t particularly progressive. My first graph shows that when combined with Stage 2, it’s broadly flat, which is how it ought to be if the government wanted to leave the progressivity of the tax system unchanged.

It is certainly not a Robin Hood package. It doesn’t take from the rich and give to the poor (except by taking tax cuts high earners thought they were going to get).

Bracket creep doesn’t only hurt high earners

The second common defence of Stage 3 is a vague reference to “bracket creep”, suggesting that if the top threshold had been indexed to inflation since it was last lifted in 2008, it would be more than $250,000 today.

Well, bracket creep (not a helpful term in my view) applies to every taxpayer. And it happens whether or not you move into a higher bracket. That’s because as income climbs, a greater chunk of it gets taxed at at the highest applicable bracket.

There are many ways of addressing bracket creep. The most obvious is to index the thresholds (including the tax-free threshold) so they climb over time in line with incomes.

Yes, it is technically true that had the top threshold been lifted in line with incomes since 2008, it would now exceed $250,000 per year. Yet, relative to the average wage, the top tax bracket doesn’t cut in at a historically low rate. You can see that in the figure below.

2008 turns out to have been a high point for where the top rate cuts in. It has fallen since, but it is still nowhere near as low as it was in the decade before the peak.

That doesn’t mean the top threshold isn’t low by international standards or that it wouldn’t be a good idea to raise it.

It’s just that even 16 years of bracket creep hasn’t pushed the top threshold to a historic low. It would probably take another 16 years of bracket creep to do that, and in any event, Albanese’s decision to lift the top threshold from $180,000 to $190,000 will push that time-frame out.

So there you have it: the two most common economic criticisms of the Stage 3 redesign are wrong. Make of it what you will, but it might give you some ammunition to use against your argumentative uncle at the next family barbecue.

Authors: Steven Hamilton, Visiting Fellow, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University