Sport is being used to normalise gambling. We should treat the problem just like smoking

- Written by Charles Livingstone, Associate Professor, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University

Turn on the TV and you’re four times more likely to see a gambling ad during a sports broadcast than during other programming.

The number of gambling ads on TV has grown from 374 a day in 2016 to 948 in 2021. The Australian Football League and National Rubgy League have an “official wagering partner”, whose logo is displayed prominently. Individual clubs have sponsorship deals with gambling companies, displaying their logos on team jerseys.

It’s something Prime Minister Anthony Albanese agrees is “annoying”, after Opposition leader Peter Dutton proposed a ban on gambling ads an hour before and after sports matches.

At present, a voluntary code governs when these ads can be shown. Generally this means they are not allowed until after 8:30pm. But as any parent will tell you, this won’t stop sports-mad kids seeing them.

Children are regularly, and heavily, exposed to these ads. Parents are alarmed at the changing way their children view sport. It’s not just about the game, or the players, or the teams any more. Now children recite bookmaker brands and the odds as they discuss the weekend’s sport.

Normalising harmful behaviour

As with cigarette marketing in decades past, sports sponsorship and advertising has been the primary mechanism for the aggressive “normalisation” of gambling. It presents betting on your team (especially with your mates) as the mark of a dedicated supporter.

Associating a product with a popular pastime, and with sporting or other heroes, is a clear tactic of harmful commodity industries from tobacco, to alcohol, fast food, and gambling.

Alarming evidence is emerging that shows how young people are influenced by this marketing. This includes evidence that young people’s exposure to gambling ads is linked to gambling activity as adults.

Gambling ads are effective in persuading people to make specific bets, and to encourage their friends to sign up.

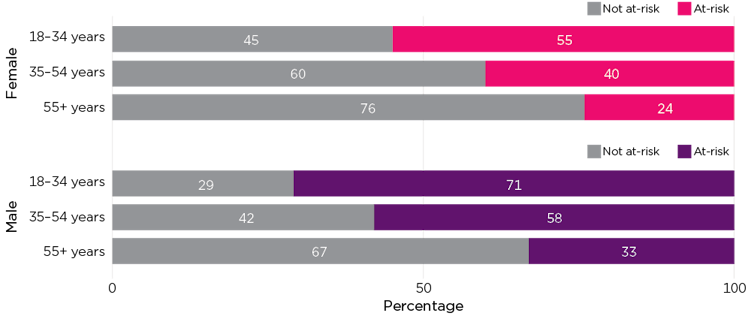

Young men are particularly susceptible. More than 70% of male punters aged 18 to 35 are at risk of harm, according to the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

What other countries are doing

These concerns have now lead to multiple countries prohibiting gambling ads altogether.

The Netherlands will ban all TV, radio, print and billboard gambling ads from July, with strict conditions on online advertising. A ban on club sponsorship will come into effect in 2025.

Belgium is going further, ban gambling ads online as well from July. It will ban advertising in stadiums from 2025, and sponsoring of sports clubs in 2028.

Spain imposed a blanket ban on gambling advertising in 2021, and Italy in 2019.

In the UK, the Premier League last month agreed to ban bookies’ logos from player match shirts, though critics argue this barely addresses the scale of the problem.

Read more: Premier League’s front-of-shirt gambling ad ban is a flawed approach. Australia should learn from it

How to denormalise harmful behaviour

“Denormalisation” was a key strategy of tobacco control efforts in Australia. These are now seen as a massive public health success, with smoking and associated disease rates dropping dramatically.

There are at least two aspects to denormalising harmful products.

The first is to reduce the avenues through which the product can be promoted. With tobacco this includes even regulating the packaging. For gambling, getting rid of all forms of gambling promotion during sporting events is the obvious first step.

It’s also important to have counter-marketing. When Victoria banned tobacco sponsorship in 1987, it established the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation , funded by tobacco taxes, initially to support teams that had lost sponsorship.

If gambling ads were banned, it would be logical to replace at least some of the bookies’ ads with messaging that helps people avoid a gambling habit, or get help if they already have an issue.

Authors: Charles Livingstone, Associate Professor, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University