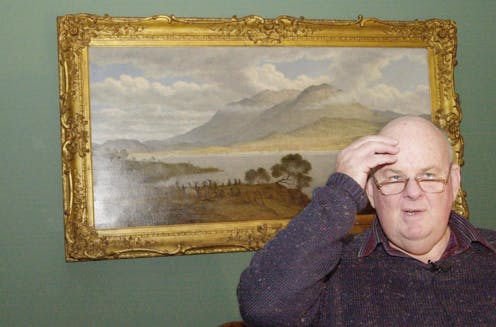

Les Murray said his autism shaped his poetry – his late poems offer insights into his creative process

- Written by Amanda Tink, PhD Candidate, Western Sydney University

An autistic author recently tweeted:

I filled out an autism quotient questionnaire for my upcoming assessment and one of the questions was about if I am fascinated by dates and I said no BUT now I want to go to the supermarket and buy some dates and see how fascinating they really are.

Reading this, I decided that a personal reevaluation of dates was definitely in order, despite our previous incompatibilities.

For me, the first hurdle in even tolerating any food is the physical experience of eating it – its initial combination of textures, and how they change during the eating process. Like Les Murray’s son Alexander, I hated “orange juice with bits in it” throughout my childhood. I still dislike the bits, but I have learned to endure them for the taste, which is my process for at least half of what I eat.

My memory of the taste of dates when I tried them as a child is sugary dirt, so they were never worth their gluey gelatinousness. But perhaps they, or I, would be different now. Intrigued by this idea, I sent the “dates” tweet to my partner, who describes himself as “having more than a hint of neuroatypicality”. He replied that he had always thought that that question referred to going out to a romantic dinner.

Of course, the non-autistic designers of the autism quotient test intended “dates” to refer only to the day, month and year of an event.

Autism and detail

These differences in word association are one reason that Les Murray identified autism as “the part of my brain […] which is mostly the part my poetry comes from”.

They also emphasise the role of context in interpretation. Though being autistic enabled the intimate relationship with detail and uncommon relationship with the world that are characteristic of Murray’s poetry, his autism often went unacknowledged when his poetry was interpreted.

Having explored the influences of autism in Murray’s poetry for a number of years, I was intrigued that autism and recontextualisation were of particular interest to him in his final collection Continuous Creation, where they often intertwine.

While Murray explicitly foregrounds his autism, some of his intentions regarding context are unclear. One example of this uncertainty is the poem Cherry Soldiers, which appears at the halfway point of the book. Here it is, in its two-line entirety:

Chokecherry, chokecherry, makin a stand:I got your little pokeberry eatin from my hand.

Caroline Overington labels this poem “fun”, which may well be the experience Murray intended it to convey as a singular poem in this collection. For me, however, it evokes the unease that I feel whenever I read it in Fredy Neptune.