Barangaroo, a masterclass in planning as deal-making

- Written by Dallas Rogers, Head of Urbanism and Associate Professor of Urban Studies, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney

The redevelopment of the 22-hectare Barangaroo precinct on Sydney Harbour has long been a masterclass in poor urban development governance and lack of due process. It was meant to transform the former docklands into a world-class example of architectural and public space design. Instead, Sydney got a world-leading example of unsolicited urbanism, and a casino.

Unsolicited urbanism is a project of city-shaping initiated by developers, not government. It clearly favours powerful development and financial players. Instead of being subject to proper public planning processes, outcomes are often predetermined.

Read more: Australian cities pay the price for blocking council input to projects that shape them

In the case of Barangaroo, secretive monopolies over the site have been legitimated. A culture of planning-as-deal-making has been normalised.

A coalition of key state government figures and the real estate and development lobbies have targeted not just this prime harbour-side site for development, but the planning system itself.

The latest furore over the site involves a proposal to modify approved plans for Central Barangaroo. The changes would greatly increase floorspace, including a new 20-storey tower above a metro train station, and shrink a public park. It’s the last tranche of buildings that will sit between the highly developed southern end and Barangaroo Reserve at the northern end.

It’s another example of how planning here operates. The planning minister and not the Independent Planning Commission will make the decision.

Read more: Crown Sydney casino opens – another beacon for criminals looking to launder dirty money

The latest chapter in a decade-long saga

The story begins with the Hill Thalis-led competition-winning entry for the Barangaroo masterplan. It was effectively discarded in 2009-2010 – revised out of existence.

Since then the public justification for the project has relied on two main arguments:

it should restore the harbour headland at the northern end of the site to something like its original form and character

its southern portion should be home to “world-class architecture” and “icons”.

The second argument was standard guff reliant on “starchitects” and the rhetoric of global landmarks.

The first was more compelling. Often rehearsed in public by former prime minister Paul Keating, the argument was that the headland was a vital aspect of the city’s most important heritage, the harbour landscape. Reconstructing it was much more important, Keating suggested, than protecting the form and some of the residual industrial heritage of the container port.

Setting aside Philip Thalis’ judgment that it is a “kitsch, historicist fantasy”, where does this leave the current proposal (modification 9) for Central Barangaroo?

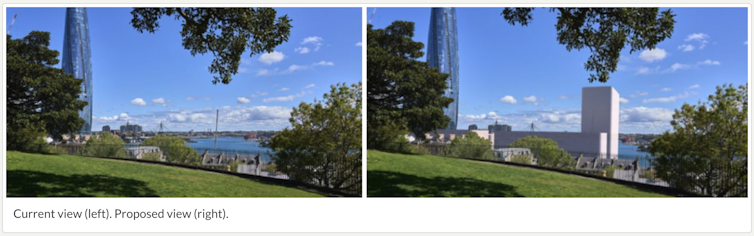

It involves notable development impact on the harbour landscape as seen from the harbour itself and from one of Sydney’s most significant public open spaces, Observatory Hill.

The expanded development and new tower would be in an area always envisaged as low-rise. The reason was to protect views and the historic landscape.

Read more: How Sydney's Barangaroo tower paved the way for closed-door deals

Part of a wider story of failure

This latest Barangaroo chapter is part of a longer story of urban governance failure.

Under the NSW Liberal government of the past decade, a raft of “reforms” have chipped away at the integrity and credibility of the planning system. Our research has tracked the longer history of how these changes have underwritten unsolicited urbanism, as shown below.

Read more https://theconversation.com/let-it-rip-barangaroo-a-masterclass-in-planning-as-deal-making-188434