the enterprise bargaining system is broken, and in terminal decline

- Written by Anthony Forsyth, Distinguished Professor of Workplace Law, RMIT University

Real wages in Australia have been stagnating for the better part of a decade. Now, with higher inflation, they’re declining. So what can the new Albanese government, having campaigned hard on the previous government’s failures, do about it?

Making a submission to Australia’s industrial relations umpire, the Fair Work Commission, to lift the minimum hourly wage from A$20.33 to A$21.36, is one thing. If that push is successful, it would help the 2% of workers paid the minimum wage, as well as the 23% (about 2.2 million workers) on awards, whose rates would also lift.

Read more: Lifting the minimum wage is anything but reckless – it's what low earners need

But there’s a bigger systemic problem the Albanese government needs to address – a flaw designed and implemented by a previous Labor government. Enterprise bargaining, the mechanism introduced 30 years ago for workers to collectively negotiate better wages and conditions, is broken.

It’s failing low-paid workers lacking bargaining power in particular, and is a big part of the reason for such poor wages in female-dominated professions such as aged care and child care.

Origin of enterprise bargaining agreements

Enterprise bargaining was introduced during the Hawke-Keating Labor era in the early 1990s, in partnership with the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the support of employer groups.

The Business Council of Australia had lobbied strongly for an enterprise focus for negotiating employment conditions, on the basis it`was the best way to tie wage claims to gains in productivity.

Prime Minister Paul Keating extols enterprise bargaining in parliament on June 24 1992.After 30 years, though, enterprise bargaining is in terminal decline, with ten years of shrinking agreement coverage in line with stagnant wages growth.

Research by labour law and policy experts Andrew Stewart, Jim Stanford and Tess Hardy published in May shows the total number of enterprise agreements fell by more than half between 2013 and 2021 (from 23,500 agreements to 10,000).

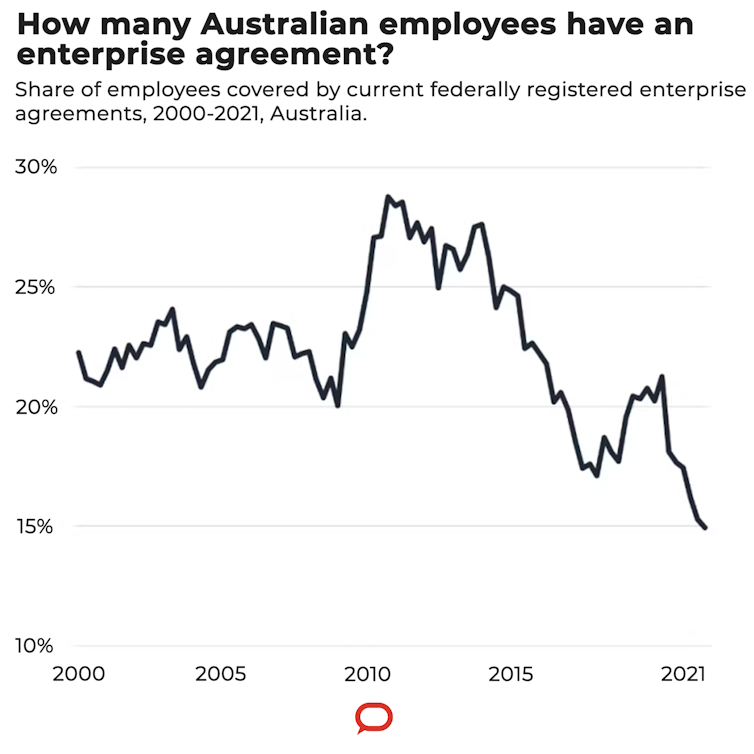

Worse, the share of employees covered by a current enterprise agreement declined from an average of 27% in 2012 to just 15% by late 2021. This is shown in the following graph.

Instead, Labor pledged to address other problems in the enterprise bargaining system: the weak requirements for employers to negotiate in “good faith”, and the ease with which employers can have agreements terminated.

However, the Albanese government may well be pushed to “go bolder” – not just by unions but also the Australian Greens, whose 2022 election policy states:

Workers should be free to collectively bargain at whatever level they consider appropriate and with whoever has real control over their work, whether at a workplace, industry, sector or other level.

The Greens’ platform also states:

Workers should have the right to engage in industrial action, including the right to strike, consistent with international law and not limited to artificially restricted bargaining periods.

The government may not need Greens’ support to pass legislation in the House of Representatives, but it will need it in the Senate.

So expect the future of enterprise bargaining, along with properly tackling insecure work, to be a hot topic for the government’s planned jobs summit.

With employers already talking up the need for productivity gains to underpin any changes, we’ll have to wait and see how serious the new government is about fixing a broken bargaining system.

Authors: Anthony Forsyth, Distinguished Professor of Workplace Law, RMIT University