Facebook ads have enabled discrimination based on gender, race and age. We need to know how ‘dark ads’ affect Australians

- Written by Mark Andrejevic, Professor, School of Media, Film, and Journalism, Monash University, Monash University

Social media platforms are transforming how online advertising works and, in turn, raising concerns about new forms of discrimination and predatory marketing.

Today the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision Making and Society (ADM+S) — a multi-university entity led by RMIT — launched the Australian Ad Observatory. This research project will explore how platforms target Australian users with ads.

The goal is to foster a conversation about the need for public transparency in online advertising.

The rise of ‘dark ads’

In the mass media era, advertising was (for the most part) public. This meant it was open to scrutiny. When advertisers behaved illegally or irresponsibly, the results were there for many to see.

And the history of advertising is riddled with irresponsible behaviour. We’ve witnessed tobacco and alcohol companies engage in the predatory targeting of women, underage people and socially disadvantaged communities. We’ve seen the use of sexist and racist stereotypes. More recently, the circulation of misinformation has become a major concern.

When such practices take place in the open, they can be responded to by media watchdogs, citizens and regulators. On the other hand, the rise of online advertising — which is tailored to individuals and delivered on personal devices — reduces public accountability.

These so-called “dark ads” are visible only to the targeted user. They are hard to track, since an ad may only appear a few times before disappearing. Also, the user doesn’t know whether the ads they see are being shown to others, or whether they’re being singled-out based on their identity data.

Severe consequences

There’s a lack of transparency surrounding the automated systems Facebook employs to target users with ads, as well as recommendations it provides to advertisers.

In 2017 investigative journalists at ProPublica were able to purchase a test ad on Facebook targeting users associated with the term “Jew hater”. In response to the attempted ad purchase, Facebook’s automated system suggested additional targeting categories including “how to burn Jews”.

Facebook removed the categories after being confronted with the findings. Without the scrutiny of the investigators, might they have endured indefinitely?

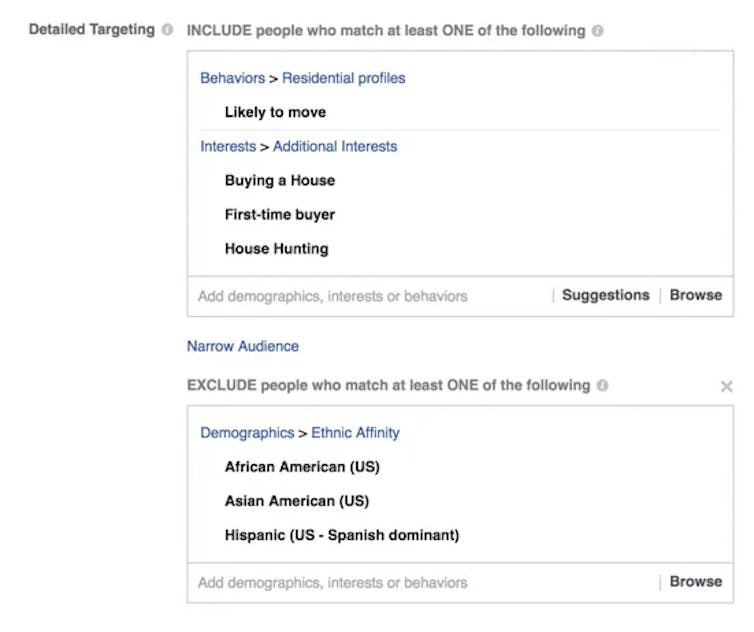

Researchers’ concern about dark ads continues to grow. In the past, Facebook has made it possible to advertise for housing, credit, and employment based on race, gender and age.

This year it was found delivering targeted ads for military gear alongside posts about the attack on the US Capitol. It also enabled ads targeting African Americans during the 2016 US presidential campaign to suppress voter turnout.

Public support for transparency

It’s not always clear whether such offences are deliberate or not. Nevertheless they’ve become a feature of the extensive automated ad-targeting systems used by commercial digital platforms, and the opportunity for harm is ever-present — deliberate or otherwise.

Most examples of problematic Facebook advertising come from the United States, as this is where the bulk of research on this issue is conducted. But it’s equally important to scrutinise the issue in other countries, including in Australia. And Australians agree.

Research published on Tuesday and conducted by Essential Media (on behalf of the ADM+S Centre) has revealed strong support for transparency in advertising. More than three-quarters of Australian Facebook users responded Facebook “should be more transparent about how it distributes advertising on its news feed”.

With this goal in mind, the Australian Ad Observatory developed a version of an online tool created by ProPublica to let members of the public anonymously share the ads they receive on Facebook with reporters and researchers.

The tool will allow us to see how ads are being targeted to Australians based on demographic characteristics such as age, ethnicity and income. It is available as a free plugin for anyone to install on their web browser (and can be removed or disabled at any time).

Importantly, the plug-in does not collect any personally-identifying information. Participants are invited to provide some basic, non-identifying, demographic information when they install it, but this is voluntary. The plug-in only captures the text and images in ads labelled as “sponsored content” which appear in users’ news feeds.

Facebook’s online ad library does provide some level of visibility into its targeted ad practises — but this isn’t comprehensive.

The ad library only provides limited information about how ads are targeted, and excludes some ads based on the number of people reached. It’s also not reliable as an archive, since the ads disappear when no longer in use.

The need for public interest research

Despite its past failings, Facebook has been hostile towards outsider attempts to ensure accountability. For example, it recently demanded researchers at New York University discontinue their research into how political ads are targeted on Facebook.

When they refused, Facebook cut-off their access to its platform. The tech company claimed it had to ban the research because it was bound by a settlement with the United States’ Federal Trade Commission over past privacy violations.

However, the Federal Trade Commission publicly rejected this claim and emphasised its support for public interest research intended “to shed light on opaque business practices, especially around surveillance-based advertising”.

Platforms should be required to provide universal transparency for how they advertise. Until this happens, projects like the Australian Ad Observatory plugin can help provide some accountability. To participate, or for more information, visit the website.

Authors: Mark Andrejevic, Professor, School of Media, Film, and Journalism, Monash University, Monash University