theatrical adaptation of hit novel blends pain with nostalgia to astonishing effect

- Written by Alastair Blanshard, Paul Eliadis Chair of Classics and Ancient History, The University of Queensland

Review: Boy Swallows Universe, author Trent Dalton, writer Tim McGarry, director/dramaturge Sam Strong at QPAC, Brisbane

There are many ways of dealing with trauma. Repression. Denial. Anger. Nostalgia? Boy Swallows Universe, the theatrical adaptation of Trent Dalton’s best-selling novel, which opened the Brisbane Festival last Friday makes a strong case for reworking and sentimentalising your pain.

The play recreates a now-lost 1980s Brisbane with such love, warmth, and enthusiasm that one often forgets just how disturbing much of the plotline really is. In this world of rotary telephones and velour tracksuits, the shorts may be way too short, but the laughs are long.

On the face of it, the subject matter of Boys Swallows Universe is grim. The content warning provided by the theatre as we entered the performance was so comprehensive and alarming (alerting us to everything from suicide, drug use and domestic violence to replica pistols and herbal cigarettes) that I began to wonder if Quentin Tarantino had been given the task of adapting the work for the stage rather than Tim McGarry.

The play came with a heavy content warning.

David Kelly

The play came with a heavy content warning.

David Kelly

When the list of impending horrors eventually concluded with a warning about strobe lighting effects, it came as a relief.

And yet, the astonishing effect of this work is that you can sit through this tale featuring heroin addiction, bodily mutilation, and murder and still leave the theatre feeling positive about humanity.

Exuberant optimism

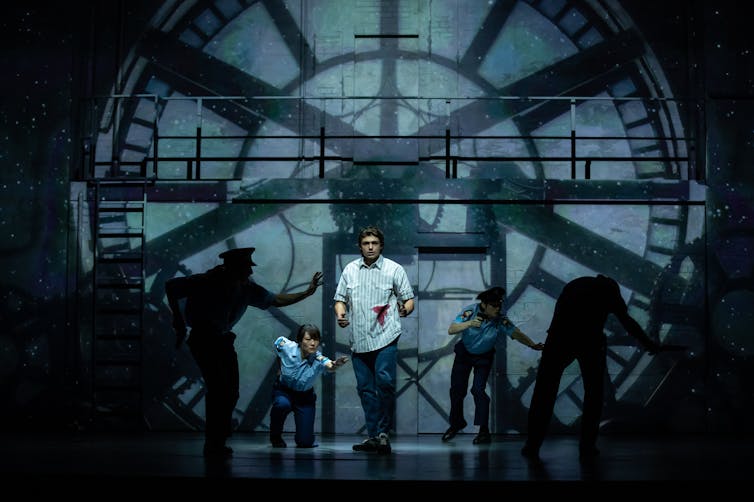

The secret lies in the genius of Dalton’s protagonist, the adolescent Eli Bell (Joe Klocek) whose exuberant optimism is more than a match for whatever life decides to throw at him. Eli is an odd mix of clueless naivety paired with extraordinary empathy. His 12-year-old legs may be hairless, but he bristles with emotional maturity. This depth allows him to be played so successfully by an older actor.

Eli’s partner is his largely mute and otherworldly brother Gus (Tom Yaxley). Together they reunite their separated parents and foil the plans of the villainous drug dealer Tytus Broz (Anthony Phelan) who for years has been bumping off his rivals using his artificial limbs business as a cover for disposing of their bodies.

Eli (Joe Klocek) and Gus (Tom Yaxley).

David Kelly

Eli (Joe Klocek) and Gus (Tom Yaxley).

David Kelly

Disclosing this eventual triumph of Eli and Gus isn’t really a spoiler. In this play, as in the novel, the journey is far more important than the almost-too-silly destination. This play is best treated as a companion piece to the novel rather than as a stand-alone work.

A catalogue of the novel’s greatest hits

Like the 1980s soundtrack punctuating its first half, this production is largely a catalogue of the novel’s greatest hits. Audience members who have not read the book may well struggle to fully understand the nature of the characters or the locations of the scenes.

Men and masculinity are the centre of this work. The question of what makes a “good man” is repeatedly posed throughout the play.

All of the men in Eli’s life are deeply flawed. They include the master of the prison escape, the “Houdini of Boggo Road”, Slim Halliday (also Anthony Phelan), a violent stepfather Lyle Orlik (Anthony Gooley), an emotionally crippled biological father (Matthew Cooper), and a sociopathic, incarcerated pen-pal (Joss McWilliam). Eli’s best friend is a shallow, foul-mouthed wannabe druglord, Darren Dang (Hoa Xuande).

Read more: Who is a real man? Most Australians believe outdated ideals of masculinity are holding men back

Somehow, Eli turns into a kind, thoughtful adult.

David Kelly

Somehow, Eli turns into a kind, thoughtful adult.

David Kelly

Somehow this dysfunctional crew manages to raise Eli into a kind, thoughtful adult. Their success is a reminder that we make a huge mistake in classifying people as either “good” or “bad”. The lesson of the play is that we need to train our eyes to see beauty in all the various shades of grey. Even the darkest soul is rarely a true black.

Given the focus on men, the female characters inevitably take a backseat. Whether it is muscular dystrophy or domestic violence, they largely exist to suffer and endure. The one exception is the karaoke-singing crime boss Bich Dang, played with gusto by Ngoc Phan. Beneath the spinning mirror balls on the stage of her Vietnamese restaurant, she is queen of all she surveys.

Darren (Hoa Xuande) and Bich Dang (Ngoc Phan). She is the queen of all she surveys.

David Kelly

Darren (Hoa Xuande) and Bich Dang (Ngoc Phan). She is the queen of all she surveys.

David Kelly

Her screeching rendition of Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft may be less Carpenters and more circular saw, but she is so fabulous you don’t care. She is far more attractive than the curiously insipid crime reporter Caitlyn Spies (Ashlee Lollback) that Eli inexplicably falls in love with.

A love letter to Brisbane

Above all, this play is a love letter to the suburbs of Brisbane. Australia is the great suburban nation, and no city is more suburban than Brisbane. The alluvial deposits of its defining river have bequeathed the city a sprawling topography where suburb gently blends into suburb.

Each community is too lacking in distinction to be treated like a village, yet not anonymous enough to be assimilated into the general urban fabric. Suburbs don’t so much colour as tint us. From the ghastly McMansions of Bellbowrie to the light industry of Darra, it is the subtlety of this shaping the play captures so well.

The word nostalgia literally means “the pain of wanting to return home”. In so effectively expressing the poetics of place, Boy Swallows Universe shows us why home will always exercise an irresistible pull.

Boy Swallows Universe is at QPAC until October 3.

Authors: Alastair Blanshard, Paul Eliadis Chair of Classics and Ancient History, The University of Queensland