a powerful, personal portrait of Aboriginal activist and filmmaker Bill Onus

- Written by Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

Review: Ablaze, directed by Alec Morgan and Tiriki Onus

Opera singer Tiriki Onus comes across a dusty, aged suitcase stowed away in the basement. It belonged to his grandfather, Bill Onus, and contains lots of still images — including young men painted up for Corroboree. Not long after, a reel of film surfaces from another archive. It has no notation or audio, but is believed to be linked to Bill Onus.

Tiriki’s interest is sparked, and he begins a quest to better understand his grandfather’s life: a man who had passed before he was born, but who loomed large.

The film Ablaze, directed by Tiriki with Alex Morgan, is the culmination of Tiriki’s quest to understand the history of the lost footage, the contents of this suitcase archive, and the grandfather he never knew.

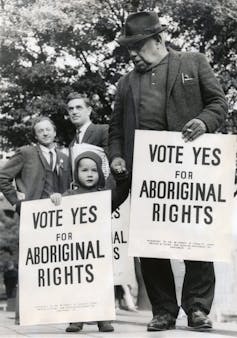

Bill Onus was a strong campaigner for Aboriginal rights.

MIFF

Bill Onus was a strong campaigner for Aboriginal rights.

MIFF

Born in 1906, Bill Onus was a civil rights activist, artist, performer and entrepreneur. He was a leading figure in his Yorta Yorta and Cummeragunja community and later at the Aboriginal epicentre of Fitzroy, Melbourne, where he lived as an adult.

As a child, Onus and his people in south eastern Australia experienced the escalating power of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board to control everyday lives and movement. Having your children removed was a constant threat. Exercising culture was prohibited. The government appointed mission managers exercised their power in cruel and inhumane ways, withholding food and quashing any objections with violence.

Read more: Capturing the lived history of the Aborigines Protection Board while we still can

As an adult, Onus was inspired by the 1933 recording of Joe Anderson (King Burraga) speaking back to this authority, and he would speak out himself through film, photography and theatre.

Across his lifetime, he created a platform for many Aboriginal artists, directed plays and curated extravagant shows to tell the stories of Aboriginal lives and culture, military service and survival.

In a nation blighted by incomprehension of Aboriginal rights, Onus’ storytelling attempted to bring to wider attention the plight of his people and the call for equality.

Film and advocacy

From a young age, Onus combined his advocacy for Aboriginal rights and passion for film.

In the 1930s, he was invited to work on Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised (1936), a cliche-ridden, Tarzan-inspired “white chief among the dangerous savages” story.

In the 1940s he worked — this time with an apparently enhanced advisory role — on Harry Watt’s The Overlanders (1946), a feature film about drovers driving a large herd of cattle some 2,500 kilometres across northern Australia.

Working on these films exposed Onus to poverty, violence and wage labour exploitation on pastoral stations beyond the south east.

Working on films and as an entertainer – including his champion Boomerang skills – Onus travelled across Australia.

MIFF

Working on films and as an entertainer – including his champion Boomerang skills – Onus travelled across Australia.

MIFF

Both Onus’ own experiences and his observations from the north fuelled his fight for Aboriginal equality and the desire to make films of his own.

As Ablaze shows, these ambitions were achieved in his documentary of the stage production White Justice in 1946. Performed at Melbourne’s New Theatre in conjunction with the Australian Aborigines league, White Justice referenced the Aboriginal strike in the Pilbara at that time.

This strike, over a vast territory of pastoral lands, saw Aboriginal workers seek independence from oppression and tyranny at the hands of the pastoralists. The now familiar images of chained Aboriginal men come from this time, a punishment in retaliation for their insubordination.

The family believes he made many more films, but they were all lost in a fire in the 1950s. Tiriki Onus’ discovery of the lost footage, including footage of the stage play, of returned Aboriginal servicemen and of Onus’ boomerang throwing prowess, finally gives an insight into the stories Bill Onus wanted to tell.

Change through stories

In Ablaze, Tiriki Onus interviews family, film historians and community leaders to understand his grandfather and the contents of the lost footage. He combines Bill Onus’ footage with other archival sources, including the expansive and now very useful files from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

Ablaze is a very personal journal, as Tiriki works to better understand what shaped his grandfather’s life and how his grandfather shaped him.

The lost footage takes us on a biographical journey that stretches out across a range of themes now familiar in the Aboriginal civil rights movement. One of the more interesting themes to emerge is Bill Onus’ comprehension of performance: how grand shows were necessary to achieve political change.

Tiriki Onus is now following in his grandfather’s footsteps.

MIFF

Tiriki Onus is now following in his grandfather’s footsteps.

MIFF

Like his grandson, Bill Onus knew storytelling: on film, the stage and in lavish theatre halls. He knew stories could be used as a vehicle for change and reach wide audiences.

Onus’ films never screened nor reached those wider audiences; the stage shows never toured nationally or internationally. But the power of First Nations film and extraordinary creative practice today finds rich lineage in his now revealed work.

Ablaze is streaming at MIFF now.

Authors: Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney