If wildlife vigilantes smuggle Tassie devils to the Australian mainland, the animals could live in secret for 20 years

- Written by Michael Bode, Professor of Mathematics, Queensland University of Technology

Tasmanian devil populations have been devastated over the past 25 years due to devil facial tumour disease, an infectious cancer. But the Tasmanian government does not support relocating uninfected wild devil populations to the Australian mainland.

Wildlife vigilantes have, however, already illegally moved Tasmanian devils off the island — an illegal practice known as “covert rewilding”. They may well might try again.

My recent research has examined this possibility. It found a covert devil population could remain undetected on the Australian mainland for years, by which time it may be too large and widely distributed to be eradicated.

In fact, it’s possible such rewilding has already occurred, and the calls of covert devils may already be echoing across the Australian Alps or Victoria’s Highlands.

A facial tumour disease is devastating Tasmanian devil populations.

Sarah Peck/AAP

A facial tumour disease is devastating Tasmanian devil populations.

Sarah Peck/AAP

What is covert rewilding?

Rewilding is the movement of a species back to a location it once existed in, either to maintain ecosystem functioning or prevent the extinction of that species.

In most countries, rewilding decisions rest with public servants in regulatory agencies, who are generally risk-averse. Rewilding proposals are generally denied, for reasons such as the need to protect other vulnerable species or prevent human-wildlife conflicts.

The overwhelming majority of conservationists operate strictly within the law. But in some cases, guerrilla conservationists take matters into their own hands.

Conclusive evidence of covert rewilding is hard to come by, for obvious reasons. But examples exist.

At Devon in the United Kingdom, beavers were discovered in 2007 in a river catchment, after an official application to reintroduce the species was resisted by government and farmers. Multiple sources believed the reappearance was the result of covert rewilding by so-called “beaver bombers”.

Similarly in the early 2000s, conservationists in Belgium illegally released beavers at two locations, where the animals subsequently formed permanent populations.

Covert rewilders released beavers to a Devon river.

Shutterstock

Covert rewilders released beavers to a Devon river.

Shutterstock

Guerrilla conservationists have also covertly relocated populations of polecats in Scotland and the Eurasian lynx in Switzerland and France.

And in Australia in 1996, unknown people covertly released Tasmanian devils onto Badger Island in Bass Strait. The devils were brought to the island by ferry and plane, and once there quickly multiplied. Their descendants were later taken back to Tasmania by officials.

Cancer-free devils have been released into wildlife refuges on the mainland under sanctioned programs, but not into the wild.

Tasmanian devils were once found in the wild across mainland Australia. Three devils were found in Victoria between 1912 and 1991, raising the possibility they were taken from Tasmania and deliberately released.

Devils are easy to catch in traps, and can tolerate captivity and transport. The Badger Island population, for example, was trapped from wild populations then taken to the island by ferry and plane. And the Australian mainland contains an abundance of suitable devil habitat.

Introducing species to ecosystems — or reintroducing species that once lived there — carries substantial ecological risks. I do not advocate for or against covert rewilding. But the practice is likely to continue, and it’s important to gain a better understanding of it.

In particular, if authorities wish to halt covert rewilding before it gets out of control, it’s important to identify and monitor the most attractive release locations.

Cancer-free Tasmanian devils have been released into mainland wildlife refuges, but not the wild.

Cristian Prieto/WildArk

Cancer-free Tasmanian devils have been released into mainland wildlife refuges, but not the wild.

Cristian Prieto/WildArk

Spreading across the landscape

A key goal of a covert rewilding is to establish a population that, by the time it is discovered, is too large to eradicate.

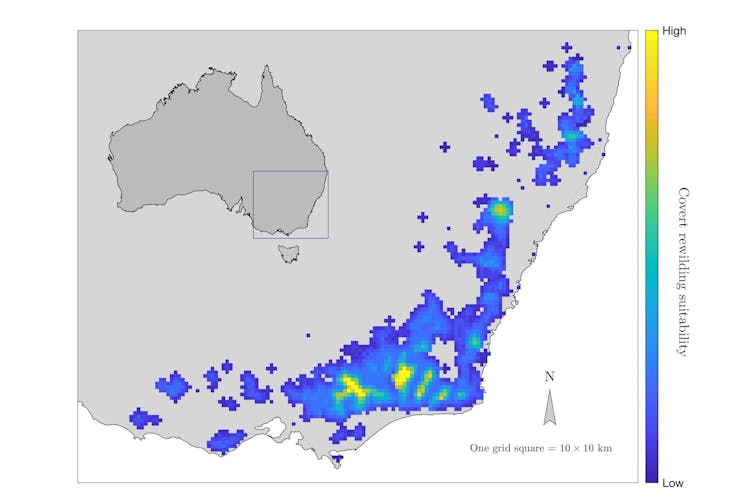

My modelling involved the hypothetical release of 40 devils at a wide range of locations across Victoria and New South Wales. I modelled how the covert population began to grow, how long it would take to be detected, and how governments could and would respond.

I calculated the annual probability of detection based on the density of the road network and the presence of towns, which affects the chance of the animals being spotted by motorists or hikers.

According to the model’s forecasts, a well-planned covert rewilding of Tasmanian devils could remain hidden for more than a decade. By the time it was noticed, the population would have increased to more than 3,000.

Three remote locations emerged as best suited to covert rewilding: two in Victoria’s Alpine National Park and one in Wollemi National Park in New South Wales. These areas had the best combination of suitable habitat, rapid spread rates and low detectability.

Yellow represents ideal covert rewilding sites for Tasmanian devils on the Australian mainland.

Author provided

Yellow represents ideal covert rewilding sites for Tasmanian devils on the Australian mainland.

Author provided

For example, following a release in Alpine National Park, the model predicted discovery by humans after 26 years, by which time the devil population would number 2,200 individuals, spread across 2,800 square kilometres. An earlier detection could easily occur, but there was a 95% chance the population would remain undetected for at least six years — reaching 100 individuals spread across 700 square kilometres.

Once two decades pass before discovery, removal would be expensive and challenging (both logistically and politically).

The lengthy detection lags identified in the research have been borne out by real-world precedents involving covert rewilding. That means if devils have been illegally reintroduced to the Australian mainland in the past two decades, we probably wouldn’t even know it.

Tasmanian devils may be roaming the mainland undetected.

Shutterstock

Tasmanian devils may be roaming the mainland undetected.

Shutterstock

Playing devil’s advocate

Additional regulation and enforcement might not dissuade guerrilla conservationists. Very few cases involving the illegal movement of wildlife in Australia lead to convictions. And some guerrilla conservationists are not deterred by fines.

From a legal perspective, covert rewilding is hard to stop because Australia’s regulatory framework is full of gaps. For example, the federal government considers species regulation to be a problem for the states, while the states consider the regulation of cross-border species relocations to be a federal problem. Rewilding, and particularly covert rewilding, falls between the cracks.

Covert rewildings typically come after official permission is denied. Often, it’s done without sufficient knowledge of the environment, species interactions and local interests.

It’s worth considering, then, if a more permissive attitude to official rewilding is needed. To quote a British beaver conservationist: “If we don’t do an official reintroduction, it’ll happen anyway”.

Read more: We developed tools to study cancer in Tasmanian devils. They could help fight disease in humans

Authors: Michael Bode, Professor of Mathematics, Queensland University of Technology