an archaeologist reports from the dig

- Written by Emlyn Dodd, Assistant Director of Archaeology, British School at Rome; Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow, Macquarie University; Research Affiliate, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens, Macquarie University

Located about 50 kilometres north of Rome, the ancient city of Falerii Novi lies buried beneath agricultural fields and olive groves. City walls still stand in an almost complete circuit and visitors pass through the monumental western gate to enter the site.

The findings from detailed ground-penetrating radar mapping were published a year ago. Now the real business of digging has begun.

At the ancient site, our teams have already discovered remnants of daily life from more than 2,000 years ago. We hope excavation will yield rare insight into antiquity with its preserved urban layout, just like at the buried city of Pompeii.

A ‘new’ city

Ancient authors Polybius and Livy tell us the city was founded by Rome in 241 BCE, following the defeat of a revolt led by the inhabitants of nearby Falerii Veteres (now Civita Castellana). According to one source, 12th-century chronicler Zonaras, Rome forcibly resettled the defeated Faliscans to a less defensible location — Falerii Novi or “new Falerii”. Its construction, intimately associated with the Roman road Via Amerina, is a rare example of preserved Roman Republican urban planning.

The Ancient Roman road Via Amerina.

Shutterstock

The Ancient Roman road Via Amerina.

Shutterstock

The city was occupied through Roman antiquity and to the early medieval period (6th and 7th centuries CE). It was on a key strategic trading route leading north from Rome, perhaps from Ponte Milvio, through central Italy.

We know little of its later history, except that the still-standing church of Santa Maria di Falleri was founded by Benedictines in 1036, disbanded in 1392 and the building was in ruins by 1571. It is now largely restored with excavated Roman roads visible beneath the floor.

When and how Falerii Novi became buried remains a mystery. How did such a large walled city become covered in so much soil? And what happened in late antiquity to cause its abandonment? The current dig may answer those questions too.

The church of Santa Maria di Falleri in 1972.

Wikimedia Commons

The church of Santa Maria di Falleri in 1972.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more: Cave of Horror: fresh fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls echo dramatic human stories

Old digs, new tricks

Three scattered attempts at excavation have been made previously. From 1821–30 a Polish team explored around the theatre area and in a (now lost) residential and commercial street-side strip. Towards the end of the 19th century work was attempted at a number of locations near city gates. And local Soprintendenza archaeologists looked at an area on the western flank of the suspected forum from 1969-75.

The site’s historical importance and immense potential, alongside developing technology, led to renewed archaeological attempts.

From 1997–8, topographic survey and surface collection were combined with magnetometry to get a broader sense of the city’s urban layout, chronology and neighbourhoods. This revealed structures including theatres, bathhouses, villas, temples and a forum a few feet under the ground.

Later, this was extended outside the city walls, revealing tombs, buildings and roads leading towards an amphitheatre.

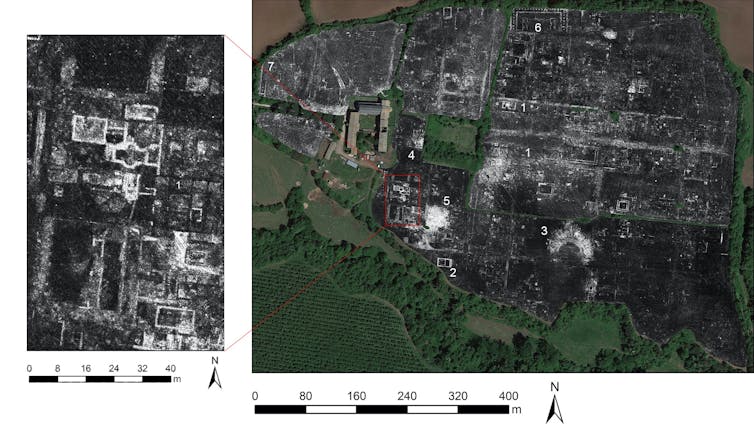

Ground-penetrating radar map of buried structures at Falerii Novi, entire city on right and detail of possible bathhouse on left.

L. Verdonck, Google Earth, Antiquity Journal

Ground-penetrating radar map of buried structures at Falerii Novi, entire city on right and detail of possible bathhouse on left.

L. Verdonck, Google Earth, Antiquity Journal

Recently a survey of the entire city using cutting-edge ground-penetrating radar produced sharper images and created a three-dimensional rendering of sub-surface features. Completely new structures were revealed, including a colossal structure, over 100 metres long, thought to be a colonnaded temple against the north city wall.

The detailed map produced by these efforts is now being used to pin-point excavation areas.

Read more: Six reasons to save archaeology from funding cuts

Breaking new ground

I’m one of the people working on the first season of systematic excavation (started in June) by a collaborative team from the Universities of Harvard and Toronto, the British School at Rome and under the concession of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per la Provincia di Viterbo e l'Etruria Meridionale.

We have opened a series of over 120 small test pits across the site. These will provide an initial understanding of various neighbourhoods — domestic, productive, religious, civic — along with chronological and spatial densities of habitation and material.

We start digging at 8am, stopping for breaks through the heat of the day, and finishing around 4pm. The work is sweaty and dirty in the hot Italian summer, but the promise of this site excites and energises everyone.

Sampling via test pits is under way but larger trenches will follow.

B. Fochetti, Author provided

Sampling via test pits is under way but larger trenches will follow.

B. Fochetti, Author provided

Work so far has revealed clues to the early occupancy of the site soon after founding in 241 BCE. What archaeologists call “black gloss ware” — a typical type of Roman Republican pottery — has been pulled out of test pits. Small pieces of Roman glass, metal slag and other ceramics are also present. Pieces of shimmering, iridescent green-glazed medieval pottery were also found, highlighting continued, post-Roman occupancy.

Next, larger-scale trenches will be opened at areas of interest. Perhaps around domestic structures and insulae (groups of buildings). Revealing the macellum marketplace, might tell us what was bought and sold, what commercial structures looked like and who was engaged in these activities. A taberna (typically a one-room shop) on the edge of the central forum may tell us about the goods and services on offer.

Read more: A batshit experiment: bones cooked in bat poo lift the lid on how archaeological sites are formed

Testing the soil

A team from Ghent University is following up previous work on site with Cambridge University. This year they are taking core samples (called augering) up to 5 metres below the current ground level. This gives archaeologists a snapshot of the site across time: human impacts on the landscape, environmental data, habitation and material changes.

Analysing core samples from up to 5m below the surface.

A. Hoffelinck

Analysing core samples from up to 5m below the surface.

A. Hoffelinck

Early results are starting to show the very real and profound effect of Roman settlement in the area. Pottery from cores also indicates occupancy over a long time, perhaps even earlier than told to us by Polybius and Livy.

Work will continue in 2022 when the first large trenches are opened and a new view of life at Roman Falerii Novi is illuminated.

Authors: Emlyn Dodd, Assistant Director of Archaeology, British School at Rome; Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow, Macquarie University; Research Affiliate, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens, Macquarie University