my belly is angry, my throat is in love — how body parts express emotions in Indigenous languages

- Written by Maïa Ponsonnet, Senior lecturer, The University of Western Australia

Many languages in the world allude to body parts to describe emotions and feelings, as in “broken-heart”, for instance. While some have just a few expressions like this, Australian Indigenous languages tend use a lot of them, covering many parts of the body: from “flowing belly” for “feel good” to “burning throat” for “be angry” to “staggering liver” meaning “to mourn”.

As a linguist, I first learnt this when I worked with speakers of the Dalabon, Rembarrnga, Kune, Kunwinjku and Kriol languages in the Top End, as they taught me their own words to describe emotions.

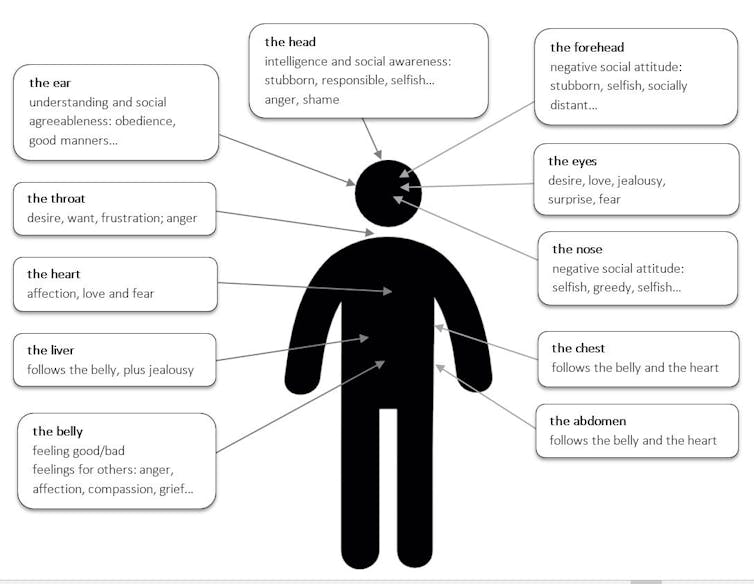

Recently, with the help of my collaborator Kitty-Jean Laginha, I have looked systematically for such expressions in dictionaries and word lists from 67 Indigenous languages across Australia. We found at least 30 distinct body parts involved in about 800 emotional expressions.

Where do these body-emotion associations come from? Are they specific to Australian languages, or do they occur elsewhere in the world as well? There are no straightforward answers to these questions. Some expressions seem to be specific to the Australian continent, others are more widespread. As for the origins of the body-emotion association, our study suggests several possible explanations.

Distribution of emotions across the body, based on 67 Indigenous languages of Australia.

Author provided

Distribution of emotions across the body, based on 67 Indigenous languages of Australia.

Author provided

Firstly, some body parts are involved in emotional behaviours. For instance, we turn our back on people when we are upset with them. In some Australian Indigenous languages, “turn back” can mean “hold grudge” as a result of this.

Secondly, some body parts are involved in our physiological responses to emotion. For instance, fear can make our heart beat faster. Indeed, in some languages “heart beats fast” can mean “be afraid”.

Thirdly, some body parts represent the mind. This can be a bridge to emotions linked to intellectual states, like confusion or hesitation. For instance, “have a sore ear” can mean “be confused”.

It is likely some body parts also end up in emotional expressions without any association in the real world. Instead, the association results from purely linguistic mechanisms (explained below).

Here are the body parts with the most emotional associations in the Australian Indigenous languages we surveyed. We cannot possibly do justice to the wealth of creative associations found in these languages, but readers who would like to know more can take a look at the website we have created explaining how this body-emotion association works.

Read more: The state of Australia's Indigenous languages – and how we can help people speak them more often

The head: intelligence and social awareness

In many languages, the head represents the mind and intelligence. This is the case in some Australian Indigenous languages too. For instance, speakers of Dalabon, in Arnhem Land, use expressions meaning “head covered” for “forget”.

The head has strong associations with shame because the mind is connected to social awareness. In many Australian groups, the notion of “shame” includes respect, which results from an understanding of social structures. Accordingly, many Australian languages, like Ngalakgan (Top End) for instance, have expressions like “head ashamed”.

More generally, intelligent people are expected to behave appropriately and therefore, the head is associated with social attitudes such as being agreeable, responsible, selfish, socially distant, obedient or stubborn, among others. In Rembarrnga (Arnhem Land), one can say “head breaks” for “be sulky”. In many languages, “hard head” means “stubborn”.

Maggie Tukumba talking about emotions in Dalabon, Bodeidei, near Weemol, 2012.

Author provided

Maggie Tukumba talking about emotions in Dalabon, Bodeidei, near Weemol, 2012.

Author provided

The forehead and nose

The forehead and the nose both symbolise negative social attitudes. There are resemblances between forehead and head expressions — which is unsurprising, since the forehead is a prominent part of the head. Most forehead expressions describe people who are stubborn (“hard forehead”), selfish, inconsiderate, or are socially distant.

The nose targets the same emotions, with a stronger focus on selfishness and greed. Many expressions associate these emotions and attitudes with the shape of the nose. That is, expressions meaning “long nose”, or “sharp nose”, can mean “selfish” as reported by the Kukatja dictionary (Western Desert).

The ears: hearing, understanding and good manners

Along with the head, many Australian Indigenous languages also associate the mind with the ear. Commonly, verbs meaning “hear” also mean “understand”; and such verbs can mean “obey” as well. Think of how, in English, people say that children “don’t listen”.

In the same vein, ear expressions associate with emotions related to compliance and agreeableness. Many Australian languages have expressions that mean literally “ear blocked”, or even more commonly “no ear”.

They describe people who are stubborn or disagreeable for instance, like in Warlpiri (Central Australia), where “hard ear” can mean “disobedient, stubborn”. Conversely, in some languages “good ear” can mean “good mannered” or “peaceful”.

Some ear expressions describe emotions that arise from uncomfortable intellectual states, like confusion or hesitation. One widespread association is between an overly active mind and emotional states of obsession. For instance, expressions that allude to “active ears” can mean “keep thinking, keep worrying about, be obsessed with”.

Ear expressions can allude to an overly active mind.

shutterstock

Ear expressions can allude to an overly active mind.

shutterstock

The eyes: desire and surprise

The linguistic association of emotions with the eyes is one of the most common in Australian Indigenous languages. Expressions with the eyes often express attraction or jealousy, as well as fear and surprise.

People tend to intensely watch those they are in love with (or jealous of), and some expressions reflect this. For example, the Kaytetye dictionary (Central Australia) reports expressions meaning literally “look with flashing eyes” to describe attraction, jealousy, or even anger.

Another common pattern is for expressions meaning “big eyes”, “eyes pop out” and the like to describe surprise, alluding to the way people look when they are surprised. We see this in the Kukatja language from the Western Desert, for instance.

Read more: Some Australian Indigenous languages you should know

The throat: love and anger

For those of us who only know English or other European languages, the association of emotions with the throat is perhaps one of the least familiar. It is indeed less common across the world than the other body part associations presented here.

It is also less widespread in Australia, mostly concentrated in certain regions. In some languages, like Alyawarr or Kaytetye, both in Central Australia, speakers use throat expressions to talk about attraction, want and frustration.

In other parts of Australia, for instance in Kaurna in South Australia, or in Pitjantjatjara in the Western Desert, the throat represents anger. The most frequent figurative representation is a dry or burning throat, usually to mean “angry”.

The belly: feelings for others

Across Australia, the belly (or stomach) is by far the most frequent body part in emotional expressions. A large number of expressions with the belly simply mean “feel good” or “feel bad”. Usually, this corresponds to “good belly” or “bad belly”.

Beyond these generic emotions, belly expressions also frequently describe what one feels towards other people. Anger is first and foremost, most typically associated with a “hot belly”. The belly also links to attachment for others, with emotions like affection, compassion, grief, etc.

Some belly expressions suggest a link between emotional states and digestive states. For instance, in Kaytetye (Central Australia), “have a rumbling stomach from something you ate” also means “feel worried or anxious” or “feel jealous”.

In Dalabon (Arnhem land), people use “tensed belly” for “anxious”. Some of us know all too well that abdominal discomfort and negative emotions often come hand-in-hand. This could have inspired the association of the belly with emotions.

Ingrid Ashley talking about emotions in Kriol, Beswick, 2014.

Author provided

Ingrid Ashley talking about emotions in Kriol, Beswick, 2014.

Author provided

Because Australian Indigenous languages contain myriads of belly expressions, they offer a wealth of creative ones. For instance, the belly is often described as hard. This can represent negative attitudes such as being unkind; as well as strength of character, which is positive.

Many expressions feature a damaged belly: it can be broken, cut, torn, among other things. In a number of languages, like Kriol, spoken in the Top End, a “cracked belly” describes the shock experienced when hearing a relative has passed away.

Some expressions evoke more violent actions, like grabbing, pushing, catching, biting, striking the belly. Most of the time, these describe negative emotions.

The heart: affection, love and fear

After the belly, the heart is the next most frequent body part in emotional expressions in Indigenous Australian languages. Some of the associations will sound familiar to speakers of English. Indeed, the heart links with love in a broad sense, including affection for relatives as well as romantic love.

However, some of the metaphors can be quite different from the English ones: in Dalabon (Arnhem Land) for instance, we find “heart sits high up” for “feeling strong affection”.

In addition, many heart expressions describe fear. Words for “fast heartbeat” sometimes mean “afraid” or “anxious”. The physical response to fear may have inspired the linguistic association.

Read more: Taking Indigenous languages online: can they be seen, heard and saved?

The liver

Liver expressions are less frequent than belly and heart ones — and don’t seem to link to a physical state of the liver triggered by emotions. Since we don’t really feel sensations in our liver, it is harder to explain why this body part is associated with emotions.

It is possible that, in some languages, liver expressions originated as belly expressions, and the word for “belly” evolved to mean “liver”. In all languages around the world, words change meaning all the time. In particular, words for body parts often evolve to designate adjacent body parts.

The emotions described by liver expressions in Indigenous languages resemble those described using the belly. Common emotions between the two include anger, affection, compassion and grief.

Some expressions may have been inspired by the external appearance of liver, observed from game or when cooked (rather than from internal sensations as with the belly and heart). Liver expressions feature colour metaphors, including “red liver”, but also “green liver”, as in Alyawarr (Central Australia), which describes jealousy.

The abdomen and chest

Expressions with words for the broader abdominal area and chest associate with the same set of emotions as the belly and heart. They also display similar metaphors.

Abdomen expressions probably started as heart or belly ones.

Dave Hunt/AAP

Abdomen expressions probably started as heart or belly ones.

Dave Hunt/AAP

In Anindilyakwa (Groote Eylandt, Top End) for instance, where speakers use a lot of chest expressions, “bad chest” means “feel bad”, and “chest dies” represents fear. Like liver expressions, chest and abdomen expressions probably started as belly or heart expressions changing meaning, as they moved to a different part of the body.

Of course, there is a lot more to learn about how the human body associates with emotions in languages, in Australia and elsewhere. To find out more, you can visit www.EmotionLanguageAustralia.com.

Or, you can open up your ears: who knows what you will hear if you listen with your heart to all those around you who know a language other than English?

I would like to express my most profound gratitude to speakers of the Dalabon, Rembarrnga, Kunwinjku, Kune and Kriol languages, who taught me the emotion metaphors of their own languages. So many people generously helped me that I cannot list them all here, but I would like to name Maggie Tukumba, Lily Bennett, Quennie Brennan, Nellie Camfoo, Maggie Jentian, Michelle Martin, June Jolly-Ashley, Angela Ashley and Ingrid Ashley.

Members of the advisory committee for EmotionLanguageAustralia are Dr Alice Gaby (Monash University), Dr Doug Marmion (AIATSIS), Dr Yasmine Musharbash (Australian National University), Denise Smith-Ali (Noongar Boodjar Language Centre) and Dr Michael Walsh (The University of Sydney). Many thanks to all the linguists who have contributed data and advice, as well as to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies for giving us access to some of the archived material.

Authors: Maïa Ponsonnet, Senior lecturer, The University of Western Australia