The TV networks holding back the future

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

If I offered you money for something, an offer you didn’t have to accept, would you call it a grab?

What if I actually owned the thing I offered you money for, and the offer was more of a gentle inquiry?

Welcome to the world of television, where the government (which actually owns the broadcast spectrum) can offer networks the opportunity to hand back a part of it, in return for generous compensation, and get accused of a “spectrum grab”.

If the minister, Paul Fletcher, hadn’t previously worked in the industry (he was a director at Optus) he wouldn’t have believed it.

Here’s what happened. The networks have been sitting on more broadcast spectrum (radio frequencies) than they need since 2001.

That’s when TV went digital in order to free up space for emerging uses such as mobile phones.

Pre-digital, each station needed a lot of spectrum — seven megahertz, plus another seven (and at times another seven) for fill-in transmitters in nearby areas.

It meant that in major cities it took far more spectrum to deliver the five TV channels than Telstra plans to use for its entire 5G phone and internet work.

Digital meant each channel would only need two megahertz to do what it did before, a huge saving Prime Minister John Howard was reluctant to pick up.

His own department told him there were

better ways of introducing digital television than by granting seven megahertz of spectrum to each of the five free-to-air broadcasters at no cost when a standard definition service of a higher quality than the current service could be provided with around two megahertz

His Office of Asset Sales labelled the idea of giving them the full seven a

de facto further grant of a valuable public asset to existing commercial interests

Seven, Nine and Ten got the de facto grant, and after an uninspiring half decade of using it to broadcast little-watched high definition versions of their main channels, used it instead to broadcast little-watched extra channels with names like 10 Shake, 9Rush and 7TWO.

Micro-channels are better delivered by the internet

TV broadcasts are actually a good use of spectrum where masses of people need to watch the same thing at once. They use less of broadcast bandwidth than would the same number of streams delivered through the air by services such as Netflix.

But when they are little-watched (10 Shake got 0.4% of the viewing audience in prime time last week, an average of about 10,000 people Australia-wide) the bandwidth is much better used allowing people to watch what they want.

Read more: Broad reform of FTA television is needed to save the ABC

It’s why the government is kicking community television off the air. Like 10 Shake, its viewers can be counted in thousands and easily serviced by the net.

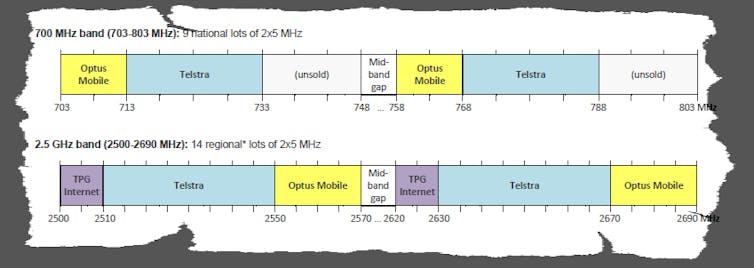

The government’s last big auction of freed-up television spectrum in 2013 raised A$1.9 billion, and that was for leases, that expire in 2029.

Among the buyers were Telstra, Optus and TPG.

The successful bidders for leases on vacated television spectrum in 2013.

Australian Communications and Media Authority

The successful bidders for leases on vacated television spectrum in 2013.

Australian Communications and Media Authority

The money now on offer, and the exploding need for spectrum, is why last November Fletcher decided to have another go.

Rather than kick the networks off what they’ve been hogging (as he is doing with community TV) he offered them what on the face of it is an astoundingly generous deal.

Any networks that want to can agree to combine their allocations, using new compression technology to broadcast about as many channels as before from a shared facility, freeing up what might be a total of 84 megahertz for high-value communications. Any that don’t, don’t need to.

All the networks need to do is share

The deal would only go ahead if at least two commercial licence holders in each licence area signed up. At that point the ABC and SBS would combine their allocations and the commercial networks would be freed of the $41 million they currently pay in annual licence fees, forever.

That’s right. From then on, they would be guaranteed enough spectrum to do about what they did before, except for free, plus a range of other benefits

The near-instant reaction, in a letter signed by the heads of each of the regional networks, was to say no, they didn’t want to share. The plan was “simply a grab for spectrum to bolster the federal government’s coffers”.

And sharing’s not that hard

It’s as if the networks own the spectrum (they don’t) and it is not as if they are normally reluctant to share — they share just about everything.

For two decades they’ve shared their transmission towers, and for 18 months Nine and Seven have been playing out their programs from the same centre.

Nine’s soon-to-be-demolished tower in Sydney’s Willoughby broadcasts Seven, Nine and Ten.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Nine’s soon-to-be-demolished tower in Sydney’s Willoughby broadcasts Seven, Nine and Ten.

Dean Lewins/AAP

That’s right. Nine and Seven use the same computers, same operators, same desks, to play programs.

One day it is entirely possible that a Seven promo or ad will accidentally go to air on Nine, just as a few years back some pages from the Sydney Morning Herald were accidentally printed in the Daily Telegraph, whose printing plants it makes use of.

All the minister is asking is for them to share something else, what Australia’s treasury describes as a “scarce resource of high value to Australian society”.

There’s a good case for going further, taking almost all broadcasting off the air and putting it online, or sending it out by direct-to-home satellite, removing the need for bandwidth-hogging fill-in transmitters.

Seven, Nine and Ten have yet to respond. Indications are they’re not much more positive than their regional cousins, although more polite. They’re standing in the way of progress.

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Read more https://theconversation.com/the-tv-networks-holding-back-the-future-155220