unravelling the knotty issue of political sideshows and Māori cultural identity

- Written by Caroline Daley, Associate Professor of History, Dean of Graduate Studies, University of Auckland

When Jacinda Ardern consoled members of the Muslim community after the Christchurch mosque attacks, she wore the hijab. Around the world, she was praised for her compassion and cultural sensitivity.

When she went to Buckingham Palace to meet the queen, she wore a kahu huruhuru, a feathered cloak. The press celebrated her choice, noting how regal she looked. The cloak was a visible sign of her mana.

People were proud that our prime minister looked so splendid and felt, by wearing the cloak, she honoured the indigenous culture of Aotearoa New Zealand.

So why have so many people been tied up in knots this week over a heitiki and a missing neck tie?

On Tuesday, parliament’s speaker, Trevor Mallard, expelled Rawiri Waititi from the House because the Māori Party’s co-leader refused to wear a tie, as per the requirements of standing orders.

Waititi likened a tie to a “colonial noose” around his neck. It was an image designed to grab attention, and international headlines.

Cultural meaning: Jacinda Ardern, wearing a kahu huruhuru, meets Queen Elizabeth II in 2018.

GettyImages

Cultural meaning: Jacinda Ardern, wearing a kahu huruhuru, meets Queen Elizabeth II in 2018.

GettyImages

Political power dressing

The stoush should not have surprised anyone. When he was sworn into the 53rd parliament, Waititi promised to challenge the status quo: “Ka tohe au! Ka tohe au! Ka tohe au!”

What might have puzzled some is that Waititi chose to challenge something so banal. The prime minister was surely right when she said there are far more important things to focus on than what a parliamentarian hangs around their neck.

Read more: New Zealand's new parliament turns red: final 2020 election results at a glance

But, as Ardern knows only too well, clothes and accessories can be a very visible and powerful statement. For Waititi, being forced to wear something he does not consider part of his culture is an act of colonisation that must be resisted.

The colonial claim may be a step too far for some, but it’s clear many agree that neck ties are no longer required business attire and they’re not very comfortable.

End of an era

No matter what knot you favour, ties can be physically restrictive. I never enjoyed wearing one as part of my school uniform. Like Mallard, I’ve never learnt how to tie a tie. Like Waititi, I choose not to wear a tie.

The notion that men in one of the most diverse parliaments in the world should still be required to wear neck ties just seems ridiculous.

Read more: Two inquiries find unfair treatment and healthcare for Māori. This is how we fix it

And it appears the majority of the Standing Orders Committee now agrees that ties should no longer be a necessity. A decision on Wednesday night meant Waititi and other men in the House will not be required to wear one. Common sense has prevailed. Parliament can focus on more serious matters.

Except, of course, that at a certain level this was a serious matter. As Waititi said, this was about cultural identity, not a tie.

Feminists have long understood this. Women had to fight to wear trousers — in the House, and in the home. They are castigated by some (and objectified by others) if their skirt is “too short” or their top “too tight”.

The sartorial is political

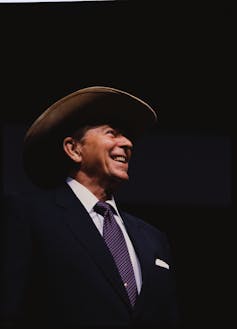

Symbols of white male power: Ronald Reagan often wore a cowboy hat.

GettyImages

Symbols of white male power: Ronald Reagan often wore a cowboy hat.

GettyImages

But many still don’t understand the politics of women’s clothes and so were confused by Waititi’s musings on clothing and cultural identity. If a neck tie is a colonial noose, why did his party co-leader, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, very pointedly wear one in the House this week?

And if Waititi is concerned that the legacy of colonisation is suppressing the tangata whenua through clothing, why does he wear a cowboy hat so often that people refer to it as his trademark?

Like neck ties, cowboy hats signify a particular type of white, male power. The most prominent politician associated with wearing a cowboy hat was former US president Ronald Reagan. One might well argue there’s a certain white extremism associated with cowboy hats that also needs to be challenged.

Read more: The Crown is Māori too - citizenship, sovereignty and the Treaty of Waitangi

Regardless of where you stand on the neck tie divide, it’s clear that clothes and accessories are political. What we buy, how we choose to wear something, and what we refuse to wear all say something about us.

Waititi has adopted the cowboy hat and imbued it with a very different meaning to those who wore their cowboy hats as they stormed the US Capitol last month. Ngarewa-Packer knotted her tie with irony.

There is nothing wrong with politicians being playful with their clothes or refusing to conform to an outdated sartorial norm. But if that is all they do, their constituents will be very disappointed.

The Māori Party has only two MPs. It would be a shame if their legacy was confined to political sideshows.

Authors: Caroline Daley, Associate Professor of History, Dean of Graduate Studies, University of Auckland