a new exhibition showcases the art hidden in medical devices

- Written by Peter Hobbins, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney

Review: Design for Life, the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

Life is messy, yet on the surface it comes neatly packaged. Our skin both enfolds and conceals internal systems that are almost infinite in their complexity. No wonder it’s our largest organ. It also mediates the way we interact with the world, from expressive facial gestures to fine hairs bristling in a cool breeze.

So it is with the technologies that sustain, renovate or enhance our bodies. Their unique shapes and sequences are traced through Design for Life, the latest biomedical exhibition at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum.

It was a delight to return to the resuscitated Powerhouse. Its collections are extraordinary and this exhibition has drawn thoughtfully on the museum’s diverse artefacts.

The thematic arrangement spans our bodily functions from blood to breathing, as well as the capabilities embodied in therapeutic devices.

Whimsy in minutiae

Within the “modification and augmentation” display, visitors can appreciate the extraordinarily delicate stitchwork that underwear manufacturers applied to crafting surgical corsets. Painstakingly laced, these garments both embraced and reshaped the healing bodies beneath.

Design for Life is a very Powerhouse exhibition. Its objects are exquisitely organised, but minimally captioned. We don’t hear the voices of practitioners or patients, nor do we see human bodies or the technology at work.

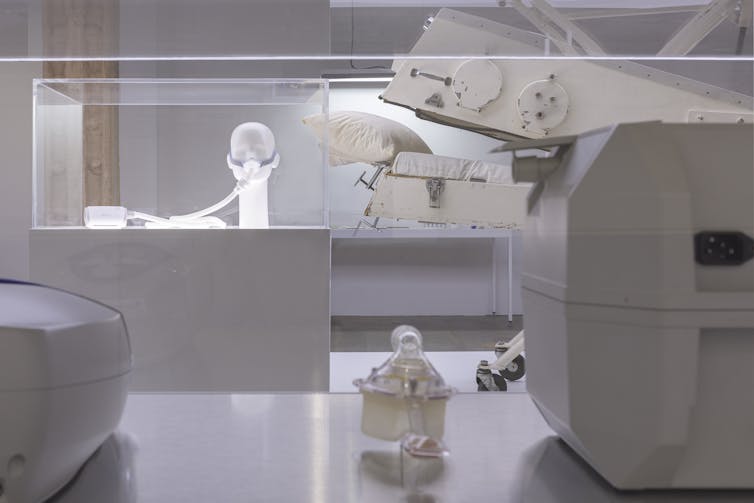

The atmosphere is archetypically clinical. The staging and lighting are serene and austere, striking in their starkness. Display cases echo the functional, stainless-steel chic of the operating theatre.

There is a sparse clinical feel to the exhibition.

Jessica Maurer/MAAS

There is a sparse clinical feel to the exhibition.

Jessica Maurer/MAAS

This sparseness draws attention to whimsical details.

Cochlear’s first prototype bionic ear from 1979 allowed users to optimise what they heard by flicking a switch to choose between “speech” or “music”.

Read more: Here's what music sounds like through an auditory implant

We can see that Telectronics upgraded their ventricular synchronised pacemaker Model PX2-B, because the code “PX2-C” has been crudely scratched onto the face plate of a prototype. Redolent of 70s-era graffiti, the date “1 – 2 – 75” is also carved roughly into its burnished and stencilled surface.

Such is the untidiness of innovation.

These minutiae matter. In 2020, the display devoted to “breath and resuscitation” is particularly pertinent.

A section on breath and resuscitation feels particularly pertinent in 2020.

Jessica Maurer/MAAS

A section on breath and resuscitation feels particularly pertinent in 2020.

Jessica Maurer/MAAS

I relished the opportunity to inspect a 1940s civilian respirator. Mass manufactured during the second world war, this rubber mask was intended to protect our domestic populace from a feared gas attack by air.

In theory, its harness could be adjusted to provide an air-tight seal against inhaled poisons. In reality, the straps on the displayed respirator are secured with three homely safety pins.

Advertising’s hidden messages

No matter their clinical utility, therapeutic products also require marketing. The cabinet on “medicine and drugs” presents pharmaceutical packaging from the 1940s onwards.

FLU OIA’, Optical Immuno Assay for the Detection of Influenza A and B, developed and made by Biota, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and Thermo Electron Corporation, Louisville, Colorado, 2004.

Laura Moore/MAAS

FLU OIA’, Optical Immuno Assay for the Detection of Influenza A and B, developed and made by Biota, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and Thermo Electron Corporation, Louisville, Colorado, 2004.

Laura Moore/MAAS

Most cartons are Spartan, comprising neatly lettered information enlivened by the occasional splash of colour. Within this boxy assemblage, a 1967 packet of Bronkephrine stands out. Featuring a cartoonish illustration of a doctor’s bag and syringe, what struck me most was its bold claim.

When used to treat asthma, promised Winthrop Laboratories, Bronkephrine would deliver “rapid, exceptionally safe bronchodilatation without tachycardia”. Clearly tachycardia – an excessively fast heart rate – had proven problematic with previous asthma remedies.

Reassuring phrases such as “exceptionally safe” have since been banned from pharmaceutical promotions. The more widely we use medical technologies, the more we accept that humans respond to them in idiosyncratic and unanticipated ways, and broad claims about safety are no longer allowed.

Read more: Pivot to pandemic: how advertisers are using (and abusing) the coronavirus to sell

This is the fundamental tension undercutting the exhibition: life is not designed. Even in rude health, humans behave in erratic or capricious ways. Our unruly fluids seep onto operating tables and we push the wrong button. We change and adapt devices, and we lose or break objects.

While the emergent design of medical artefacts may represent new technological possibilities, it can also reflect the impact of ignorance, accidents or whimsy.

MicroRapid lateral flow blood test device and prototypes, designed and made by Atomo Diagnostics and ide Group, Newington Technology Park, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2013.

Laura Moor/MAAS

MicroRapid lateral flow blood test device and prototypes, designed and made by Atomo Diagnostics and ide Group, Newington Technology Park, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2013.

Laura Moor/MAAS

The medical utility of the hardware store

This is why my favourite object in Design for Life is a carbon surgical laser, introduced by Laser Industries in 1979. The battleship-grey device looks more like an assembly-line robot than a precision incision tool.

Yet it is entirely humanised. Printed operating instructions have been slipped into a cheap plastic sleeve and sticky-taped to its top surface. “If you are uncertain how to look after [the] machine”, they conclude, “please leave it for someone who does”.

The back of the laser unit reminds me of a patient who forgot to lace up their hospital gown, exposing their posterior to an unappreciative ward.

Here we find a chipped gas cylinder plastered with inspection certificates and stickers; a stencilled filter unit; yellowed tubing and electrical leads. Seemingly critical to the laser’s operation is a coiled length of garden hose, complete with an orange Nylex connector as found in backyards across Australia. Struggling to discipline these writhing and disorderly attachments is a length of hardware-store galvanised chain.

This is the reality of healthcare design: much as we might aim for purity of form, function, communication or operation, medical devices are never merely objects. They live with us – or within us – in all of our chaotic unpredictability. Life eludes our designs.

Yet this exhibition confirms the touching endurance of our belief one day – just maybe – we will actually be in control.

Design for Life is on at the Powerhouse Museum until January 31, 2021.

Authors: Peter Hobbins, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney