Young African migrants are pushed into uni, but more find success and happiness in vocational training

- Written by Tebeje Molla, Research Fellow, Deakin University

For disadvantaged people with disrupted educational trajectories, such as refugees, vocational qualifications can widen access to paid jobs and enhance economic independence. But many still consider vocational education and training (VET) qualifications not as prestigious as university degrees. This is a widespread issue, especially in African communities.

Many African parents push their children to go to university regardless of their preparedness or interest. The outcome is dispiriting. Most of them leave university without a degree. They drop out.

But African youth I have interviewed for as-yet unpublished research have found VET in Australia to be a supportive environment, where they have been successful. More should be encouraged to consider VET, and policies must be in place to help them get there.

Unequal trends of higher education participation

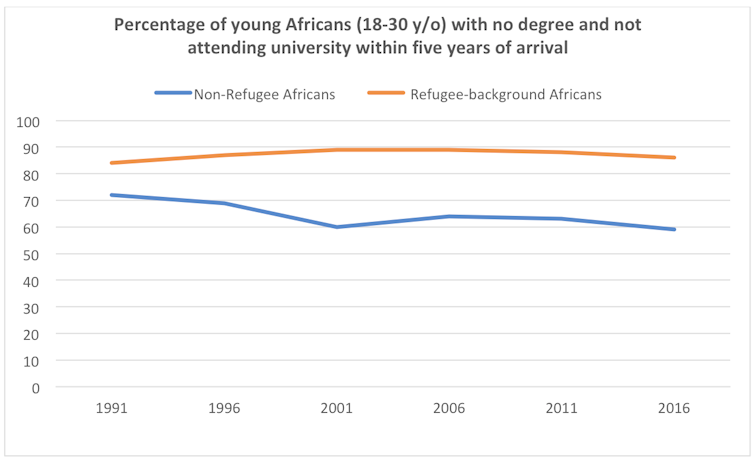

For African Australians, higher education attainment is closely associated with migration status. Compared to their non-refugee counterparts, refugee background African youth are less likely to transition to university within five years of their arrival in Australia. The trend has not changed much over the last 25 years.

Author provided

This difference between the two groups can in part be explained by the fact African refugee youth arrive with limited educational attainment. For instance, in 2016, 19% of people (aged 15 years and over) born in the main countries of origin of African refugees had no qualifications. The corresponding rate for the non-refugee African population was 10%; for the total Australian population, it was 8.5%.

But the persistence of the problem warrants policy attention.

VET is an equaliser

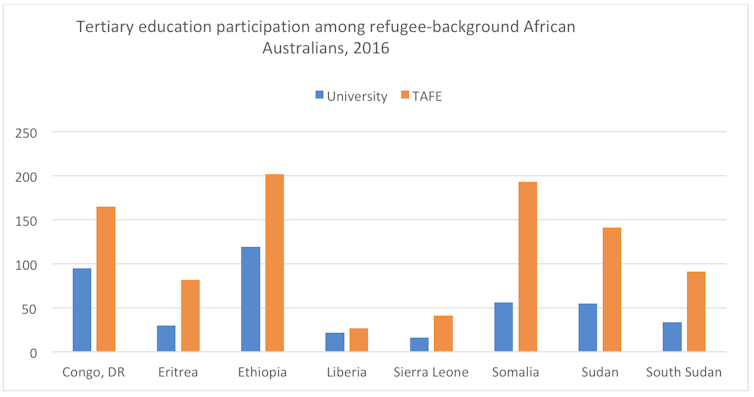

People from the main countries of origin of African refugees (Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan) have considerably benefited from the VET sector.

The VET sector provides them with an equity pathway to university. For many students from refugee background, low academic results at school mean a direct transition to university remains challenging. In 2016, there were close to 1,000 Africans from refugee background in the VET sector compared to fewer than 500 in the university sector.

Author provided

This difference between the two groups can in part be explained by the fact African refugee youth arrive with limited educational attainment. For instance, in 2016, 19% of people (aged 15 years and over) born in the main countries of origin of African refugees had no qualifications. The corresponding rate for the non-refugee African population was 10%; for the total Australian population, it was 8.5%.

But the persistence of the problem warrants policy attention.

VET is an equaliser

People from the main countries of origin of African refugees (Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan) have considerably benefited from the VET sector.

The VET sector provides them with an equity pathway to university. For many students from refugee background, low academic results at school mean a direct transition to university remains challenging. In 2016, there were close to 1,000 Africans from refugee background in the VET sector compared to fewer than 500 in the university sector.

Author provided

The majority of African youth I interviewed in the last two years came to the university sector through VET, using the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) pathway. They said passing through TAFE helped them develop their “navigational capacity” — their ability to plan and work towards future goals. They specifically noted the supportive learning environment in TAFE institutes prepared them for independent learning. It set them up for success in university.

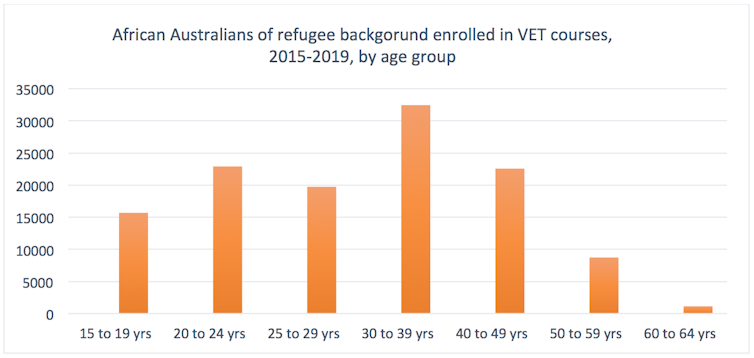

VET courses also give African Australians a second chance. Africans from refugee backgrounds attend vocational courses as mature age students, with the largest age group being 30 to 39 year olds. For the general Australian population, the largest age group enrolled in VET courses was 15 to 19 year olds.

Author provided

The majority of African youth I interviewed in the last two years came to the university sector through VET, using the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) pathway. They said passing through TAFE helped them develop their “navigational capacity” — their ability to plan and work towards future goals. They specifically noted the supportive learning environment in TAFE institutes prepared them for independent learning. It set them up for success in university.

VET courses also give African Australians a second chance. Africans from refugee backgrounds attend vocational courses as mature age students, with the largest age group being 30 to 39 year olds. For the general Australian population, the largest age group enrolled in VET courses was 15 to 19 year olds.

Author provided

Despite limited educational attainment at arrival, refugee-background African Australians are over-represented in VET courses. In the 2016 census, people born in the eight main countries of origin of African refugees accounted for less than 0.3% of the total population of Australia. But the group represented about 1.3% of the total enrolment in funded VET programs and courses in the last five years (2015-2019).

Between 2015 and 2019, there were more than 91,000 refugee-background African Australians enrolled in VET courses, and over that same time period, 20,000 completed VET courses.

In the university sector, a total of close to 11,000 African refugee youth enrolled for undergraduate degrees between 2001 and 2017. But fewer than 2,000 of those successfully completed their courses over the same period.

Author provided

Despite limited educational attainment at arrival, refugee-background African Australians are over-represented in VET courses. In the 2016 census, people born in the eight main countries of origin of African refugees accounted for less than 0.3% of the total population of Australia. But the group represented about 1.3% of the total enrolment in funded VET programs and courses in the last five years (2015-2019).

Between 2015 and 2019, there were more than 91,000 refugee-background African Australians enrolled in VET courses, and over that same time period, 20,000 completed VET courses.

In the university sector, a total of close to 11,000 African refugee youth enrolled for undergraduate degrees between 2001 and 2017. But fewer than 2,000 of those successfully completed their courses over the same period.

More VET students complete their course.

Shutterstock

Public investment is necessary

In the post-COVID world, Australia’s success will largely depend on the adaptability and responsiveness of the education system. It will be critical to ensure disadvantaged members of society do not slip through the policy cracks.

Refugees in particular require extra support to succeed in education and training. For instance, African refugees arrive with a level of disadvantage not experienced by other cohorts of refugees.

We need to acknowledge the unique situation of African refugees and provide them with targeted policies. For refugee youth who spent years in refugee camps with little or no education, it can be difficult to fit in a school system that operates on age cohorts. There is a need for expanding the “catch-up schooling” that is offered for young refugees and diversifying the existing pathways to tertiary education.

Refugee status should also be recognised as a category of disadvantage in the higher education sector. Recognising refugees as an equity group enables tertiary education institutions to provide the necessary support for success.

Without access to lifelong learning opportunities, refugees are likely to remain vulnerable to fast-paced changes in the world of work.

Educational attainment is instrumental for integration and economic independence. African American civil right activist Ella Baker’s truism “Give people light and they will find the way” aptly encapsulates the self-reliance that comes with learning.

More VET students complete their course.

Shutterstock

Public investment is necessary

In the post-COVID world, Australia’s success will largely depend on the adaptability and responsiveness of the education system. It will be critical to ensure disadvantaged members of society do not slip through the policy cracks.

Refugees in particular require extra support to succeed in education and training. For instance, African refugees arrive with a level of disadvantage not experienced by other cohorts of refugees.

We need to acknowledge the unique situation of African refugees and provide them with targeted policies. For refugee youth who spent years in refugee camps with little or no education, it can be difficult to fit in a school system that operates on age cohorts. There is a need for expanding the “catch-up schooling” that is offered for young refugees and diversifying the existing pathways to tertiary education.

Refugee status should also be recognised as a category of disadvantage in the higher education sector. Recognising refugees as an equity group enables tertiary education institutions to provide the necessary support for success.

Without access to lifelong learning opportunities, refugees are likely to remain vulnerable to fast-paced changes in the world of work.

Educational attainment is instrumental for integration and economic independence. African American civil right activist Ella Baker’s truism “Give people light and they will find the way” aptly encapsulates the self-reliance that comes with learning.

Authors: Tebeje Molla, Research Fellow, Deakin University