will she let a mine destroy koala breeding grounds?

- Written by Lachlan G. Howell, PhD Candidate | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

In the next few weeks, federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley will decide whether to approve a New South Wales quarry expansion that will destroy critical koala breeding grounds.

The case, involving the Brandy Hill Quarry at Port Stephens, is emblematic of how NSW environment laws are failing wildlife — particularly koalas. Efforts to erode koala protections hit the headlines last week when NSW Nationals leader John Barilaro threatened to detonate the Coalition over the issue.

Read more: The NSW koala wars showed one thing: the Nationals appear ill-equipped to help rural Australia

Koala populations are already under huge pressure. A NSW parliamentary inquiry in June warned the koala faces extinction in the state by 2050 if the government doesn’t better control land clearing and habitat loss.

Ley could either continue these alarming trends, or set a welcome precedent for koala protection. Her decision is also the first big test of federal environment laws since an interim review found they were failing wildlife. So let’s take a closer look at what’s at stake in this latest controversy.

This female koala is under threat from the Brandy Hill Quarry expansion.

Lachlan Howell, Author provided

This female koala is under threat from the Brandy Hill Quarry expansion.

Lachlan Howell, Author provided

The Brandy Hill Quarry expansion

The NSW government gave approval to Hanson Construction Materials, a subsidiary of Heidelberg Cement, to expand the existing Brandy Hill Quarry in Seaham in Port Stephens.

The project would provide concrete to meet Sydney’s growing construction demands, as the state fast-tracks infrastructure projects to help the economy recover from COVID-19.

The approval came despite the known presence of koalas in the area. A koala survey report, completed on behalf of the developer in 2019, determined the project would “result in a significant impact to the koala”.

The report recommended the quarry expansion be referred to the federal Environment Minister under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999, for its potential impacts on “Matters of National Environmental Significance”.

Read more: View from The Hill: Barilaro keeps Nationals in the tent; koalas stay in limbo

The expansion site intersects habitat with preferred high quality koala feed and shelter trees. This habitat is established forest containing various key mature Eucalyptus trees, including the forest red gum and swamp mahogany.

The survey report didn’t propose any mitigation strategies to sustain the habitat. Instead, it suggested minimisation measures, such as ecologists to be present during habitat clearing, low speed limits for vehicles on site, and education on koalas for workers.

A disaster for koalas

In support of a community grassroots campaign (Save Port Stephens Koalas), we produced an report on the effect of the quarry expansion on koalas. The report now sits with Ley ahead of her decision, which is due by October 13.

Male koalas will bellow during the breeding season to attract females.The expansion will clear more than 50 hectares of koala habitat. We found koalas breeding within 1 kilometre of the current quarry boundary, which indicates the expansion site is likely to destroy critical koala breeding habitat.

During the breeding season, male koalas bellow to attract females. Within 1km of the boundary we observed a female koala and a bellowing male koala 96m apart. A second male was reported bellowing 227m from the quarry boundary.

What’s more, the site expansion occurs within a NSW government listed Area of Regional Koala Significance. The expansion site actually has higher average koala habitat suitability than all remaining habitat on the quarry property.

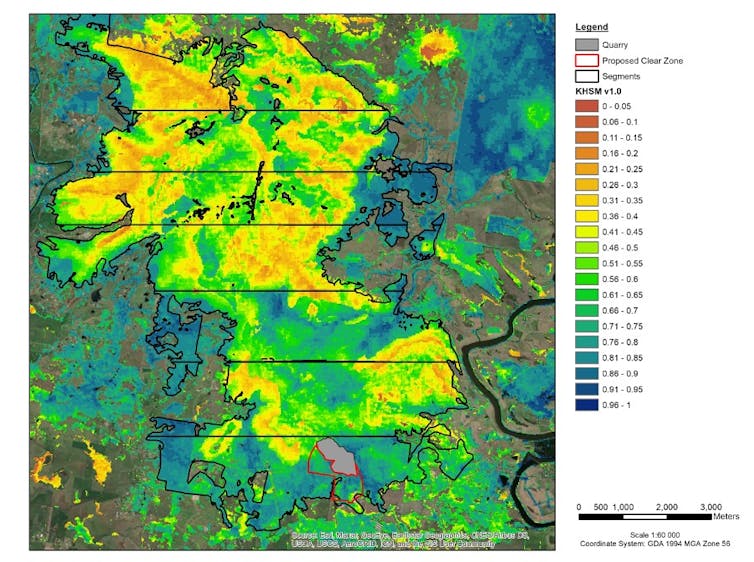

The Koala Habitat Suitability Model from our independent report. The red boundary represents the Quarry expansion site containing high habitat suitability.

Map produced by S. A. Ryan using the Koala Habitat Information Base and arcGIS 10.6., Author provided

The Koala Habitat Suitability Model from our independent report. The red boundary represents the Quarry expansion site containing high habitat suitability.

Map produced by S. A. Ryan using the Koala Habitat Information Base and arcGIS 10.6., Author provided

CSIRO research from 2016 suggests koalas in Port Stephens can move hundreds of metres in a day and up to 5km in one month. Movement is highest during the breeding season. This potential for koalas to move away was a key reason the NSW government approved the expansion.

Koalas can move in to the remaining property to breed, or they can move away from it. But habitat outside the expansion site is, on average, lesser quality, and this is where the expansion would force the koalas to move to.

Read more: Stopping koala extinction is agonisingly simple. But here's why I'm not optimistic

This habitat fragmentation would not only result in lost access to potential breeding grounds, but also further restrict movement and expose koalas to threats such as predation or road traffic.

Lastly, the expansion would sever a crucial East–West corridor koalas likely use to move across the landscape and breed.

Approved under the state’s weak environmental protections

It may seem surprising this destructive project was approved by the NSW government. But it’s a common story under the state’s protections.

Alarm over the weaknesses of NSW environmental protections has been raised by NSW government agencies including the Natural Resources Commission and NSW Audit Office.

The expansion approval is an example of how the NSW government relaxed the regulatory requirements for land clearing between 2016 and 2017. This led to a 13-fold increase in land clearing approvals, and tipped the balance away from sustainable development.

Female and male koalas spotted 1 km from the quarry boundary. The male was observed bellowing 96 m from the female koala. Photo: Lachlan Howell.

Female and male koalas spotted 1 km from the quarry boundary. The male was observed bellowing 96 m from the female koala. Photo: Lachlan Howell.

The expansion shines another spotlight on NSW’s poor biodiversity offset laws.

Biodiversity offsets involve compensating for environmental damage in one location by improving the environment elsewhere. Under the expansions approval, the developer was required to protect an estimated 450 hectares of habitat as offset.

But the recent parliamentary inquiry into NSW koalas recommended offsetting of prime koala habitat — such as that involved in the quarry expansion — be prohibited, which would mean not destroying the habitat in the first place.

The NSW decision also does not account for the Black Summer Bushfires which claimed 5,000 koalas and burned millions of hectares of koala habitat. The Port Stephens population was unburned but more than 75% of its habitat has been lost since colonial occupation. Securing this population is important for the overall security of koalas in the state.

The koalas are in Sussan Ley’s hands

Sussan Ley will now assess the expansion under the EPBC Act. A recent interim report into the laws said they’d allowed an “unsustainable state of decline” of Australia’s environment.

Rejections under these laws are rare; just 22 of 6,500 projects referred for approval under the act have been refused. However, it’s not impossible.

Earlier this year Ley rejected a wind-farm in Queensland which threatened unburned koala habitat. If Ley gives full consideration to the evidence in our report, she should make the same decision.

Read more: Be worried when fossil fuel lobbyists support current environmental laws

Authors: Lachlan G. Howell, PhD Candidate | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle