they are not necessarily particularly vocal

- Written by Peter Robertson, Professor, University of Western Australia

Businesses are protesting vociferously about Victoria’s extended lockdown. It’s “gut-wrenching,” “devastating,” a “trainwreck,” a “death knell”.

Yet businesses and shareholders are far from representative of those most at risk.

The best evidence we’ve got suggests the hardest hit are Victoria’s already disadvantaged.

Those arguing for extended lockdowns make the point that they are not as costly as they might seem (to anyone) because their effects need to be compared not with business as usual, but with business in which a pandemic encourages people to stay at home and reduce spending.

Australia’s recession began during the March quarter, almost all of which was before the lockdowns began on March 24.

Victoria’s job losses accelerated well ahead of the renewed Stage 3 and then Stage 4 lockdowns which began on July 8 and August 2.

In the United States it has been found that lockdowns only had a modest effect on job losses compared to what came before; one estimate is 10%.

Lockdowns hurt some more than others

But these are overall measurements. Lockdowns hurt some much more than others.

A study of 29 European Union nations found that people with high levels of education were twice as likely as people with low education to be able to work through lockdowns.

A British study found employees in the bottom 10% of earnings were seven times as likely as those in the top 10% to work in a sector that had been shut down.

An Australian study found low income workers were three times as likely as high earners to face a high risk of losing their jobs.

Mobility data shows it

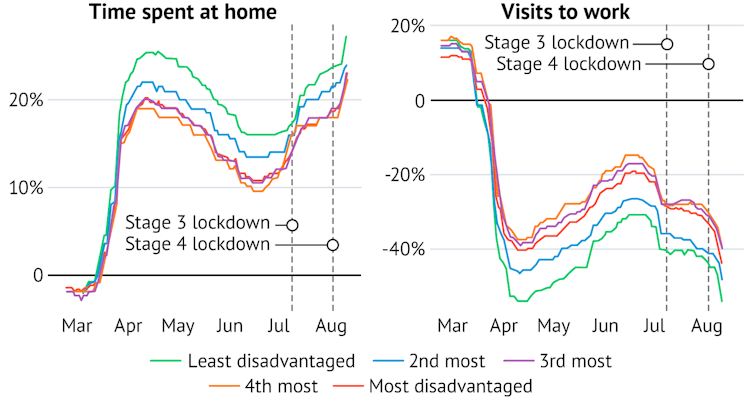

This isn’t obvious from mobility data, which seems to show the opposite.

Google statistics on the movement of people with Android phones show that residents of Melbourne’s most disadvantaged suburbs have restricted their travel the least.

Source: The Age, Nicolas Rebuli

The most likely reason that economically and socially disadvantaged Melbourne residents are still moving is that they are in jobs that don’t allow them to work from home.

A World Bank study finds the same thing on a larger scale. The extensive voluntary reductions in activity that proceeded lockdowns were present in only rich nations, not in developing ones.

This means, in the words of a Harvard University study, that in countries where many people live at or close to subsistence, it isn’t possible to save people from the pandemic without condemning them to deprivation.

The story is as old as the plague itself.

Read more:

Why coronavirus will deepen the inequality of our suburbs

During the Black Death of 1348 to 1349, King Edward fled London with his relics and staff for the safety of his country estates. The poor had nowhere to flee. Even though the odds of surviving the year in London were less than 50%, the odds of surviving without work weren’t much different.

During Great Plague of London in 1655, so many people of means deserted the city that it was dubbed “the poore’s plague”.

Throughout history and across countries, disadvantaged groups necessarily have fewer choices and hence carry a greater share of the burden of quarantine-type measures.

We should expect business to represent the interests of its shareholders - and business claims should be viewed through that lens, but there are other victims of lockdowns, less able to provide ready quotes.

However well intentioned the lockdowns are, the already-disadvantaged are likely to be hurting the most.

Source: The Age, Nicolas Rebuli

The most likely reason that economically and socially disadvantaged Melbourne residents are still moving is that they are in jobs that don’t allow them to work from home.

A World Bank study finds the same thing on a larger scale. The extensive voluntary reductions in activity that proceeded lockdowns were present in only rich nations, not in developing ones.

This means, in the words of a Harvard University study, that in countries where many people live at or close to subsistence, it isn’t possible to save people from the pandemic without condemning them to deprivation.

The story is as old as the plague itself.

Read more:

Why coronavirus will deepen the inequality of our suburbs

During the Black Death of 1348 to 1349, King Edward fled London with his relics and staff for the safety of his country estates. The poor had nowhere to flee. Even though the odds of surviving the year in London were less than 50%, the odds of surviving without work weren’t much different.

During Great Plague of London in 1655, so many people of means deserted the city that it was dubbed “the poore’s plague”.

Throughout history and across countries, disadvantaged groups necessarily have fewer choices and hence carry a greater share of the burden of quarantine-type measures.

We should expect business to represent the interests of its shareholders - and business claims should be viewed through that lens, but there are other victims of lockdowns, less able to provide ready quotes.

However well intentioned the lockdowns are, the already-disadvantaged are likely to be hurting the most.

Authors: Peter Robertson, Professor, University of Western Australia